TT JOURNAL, VOL.1, ISSUE 3, 8TH OCTOBER 2021

by Sarah McCartney

“You don’t have to wear a mask now,” said a mask-free waiter. “We’re back to normal.”

But I did, because we aren’t.

In a basement, windowless club, at an event I’d hoped would be cancelled, only two of us were wearing masks and the other one took hers off.

“I’ve got you antibacterial gel,” said the organiser.

“It’s a virus,” I say, “Antibacterial gel doesn’t work on viruses.” I got an eyeroll for that.

Right now, one in a hundred people in the UK have Covid-19.

On average, one of those people will give it to one more person.

50% of people who catch it lose their sense of smell. One in a hundred of those people won’t get it back.

That probably doesn’t seem significant, unless your days are spent blending aromas to make new ones, and you really need a functional relationship between your nose and your brain.

I was vaccinated; I thought I might be safe. Then we had “freedom day”, and I became a recluse. Otherwise reasonable people have decided to believe that everything is fine now.

The people I work with go out now – because it’s allowed – to festivals, football matches, meals, parties and pubs. Allowed = fine, safe, encouraged. People I know have divided into the majority of outgoers and a minority of instayers.

“I don’t really think there’s much risk of you dying now.”

That’s not the point. I’m afraid of losing my sense of smell, of it being handed back to me damaged, or never meeting it again. I’m afraid of losing my work, and the work of those people who work with me. But they don’t see it; they think I’m worrying for no reason. Now I wear a mask in my own workplace.

“We’ve got to get back to normal.”

But we don’t. We had the chance to go forward to different, or sideways to unusual. It’s disappointing.

For six months, we changed because we had to. We pivoted, swivelled, adapted, paused, reconsidered, discovered, waited, reset and feared. Working from home. Going for walks. Learning the skills we’d always hoped we could have.

I packed up my perfumery materials and took them home. I created new fragrances and rewrote all my classes so scent students could make fragrances in their homes instead of visiting my studio. Here we stay, unable to hand paper scent strips to each other and smell our diverse creations. But able to take part from other continents, follow the same formulas and share our diverse opinions. It’s completely different, and I like it better.

What else would we change? Formulas are secret and perfumes are flown around the world so the aroma can be shared. We could share formulas so that anyone could make the perfume wherever they are. More making, fewer boxes accumulating fewer air miles. Less waste, more knowledge. I tried it and it works.

What about the materials we use? Can we be better? So many fields ploughed into wild land, to grow roses and vetiver. So many rosewood and oudh trees illegally logged. Children delicately pollinating vanilla orchids to fulfil the demand from people who don’t know or care about the ethics of their perfume as long as it’s “natural”.

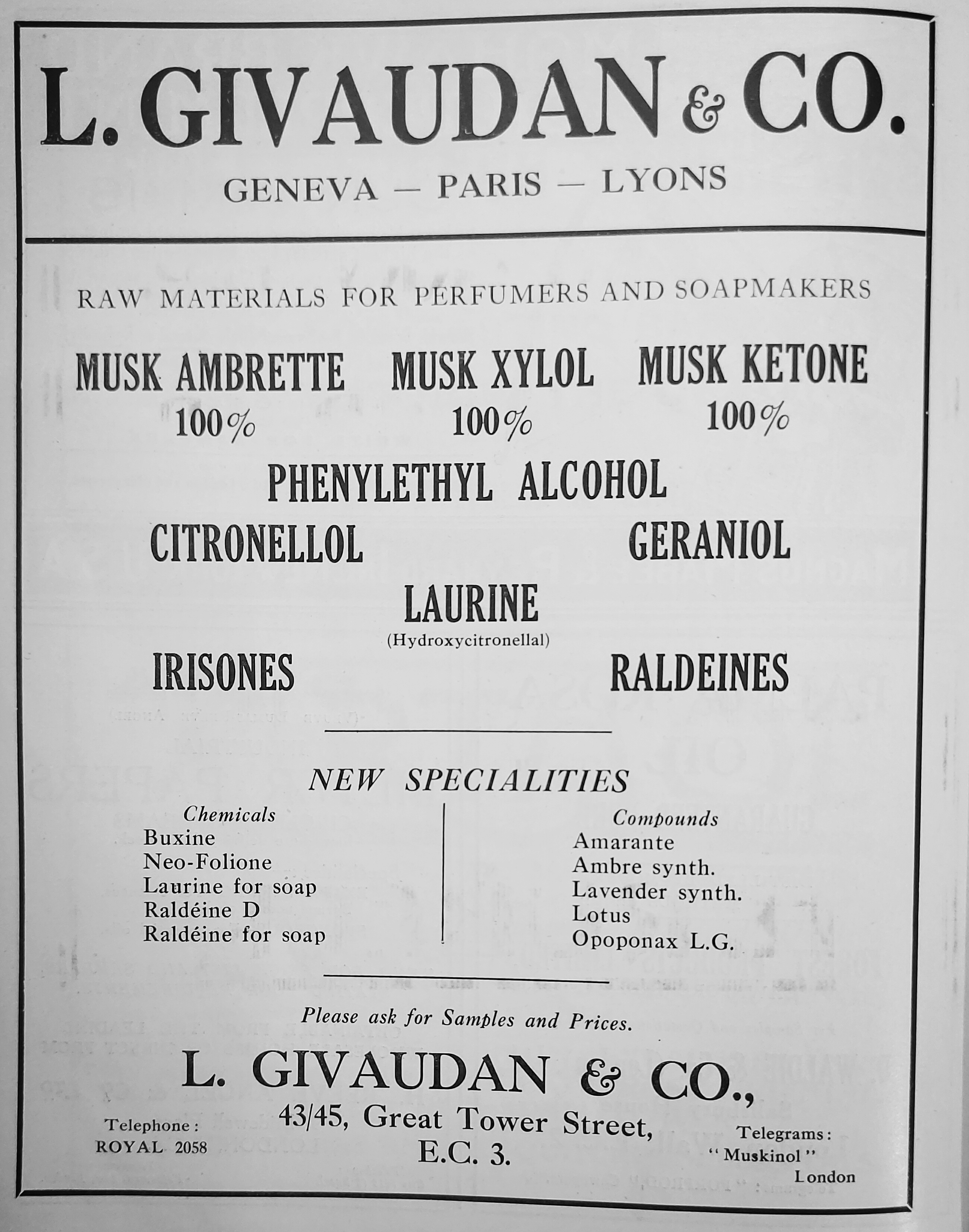

It’s not natural for a million rose petals to leap into oil, then into a distillery to be extracted into 1kg of rose perfume. Phenyl ethyl alcohol made in a shiny clean German factory might be better for our planet than bulldozing, spraying and watering hectares of Morocco for the “natural” version..

The move towards sustainable scents is exhilarating. It feels as if we’re attached to a zipwire and we’re zooming along, the way we used to zoom before Zoom, which doesn’t zoom at all. The future is not necessarily natural, but it’s biodegradable and renewable. We have green chemistry, upcycled materials, vertical farming: hydroponic underground multi-layered herb farms to grow “natural” mint to make organic toothpaste for artificially whitened, straightened teeth.

Thinking about herbs grown metres underground, never feeling the sun on their leaves, I get vicarious claustrophobia.

While Zooming about Ophelia we noted how narcissistic life inside a screen has made us. In a real room we don’t see ourselves. Now, our tiny selves stare in a different direction, rather than right back at us. Zoom us can’t look us in the eye.

Narcissus then, made from a species grown in the Auvergne, or a recreation made by aromachemists? It has to be the recreation.

Rose? Let’s use a material made from the upcycled remains of the first harvest, Rose Ultimate. New technology to save waste.

I need waterlilies for Ophelia, and for this a new material fell into my world. Renewable and biodegradable, with the aroma of flowers and fruits as yet undiscovered, growing by a flowing stream. It is a single molecule material which smells like a finished fragrance all on its own. Such complex beauty from a synthetic chemical. Its name is Hydrofleur and it is perfect for us. It’s not made from flowers; no flowers were harmed in the making…

“Is it real flowers?”

The fragrances which people declare to be their favorite “fresh natural” aromas are often 100% synthetic. If you make a fragrance from nothing but natural floral materials it will smell pretty awful, no matter how much money you throw at it. (Natural narcissus absolute is about £12000 a kilo.)

When people were able to travel wherever they wanted, they filled their houses with artificial aromas of the countryside, olfactory observations of solitude. Enclosed and isolated, they bought smells of the beach, funfairs and coffee shops. Places where others buzzed.

Perhaps what we need in our screened-off lives is the aroma of other people. Or would that make it feel worse?

Sarah McCartney is an artisan perfumer working in Hammersmith, West London. She runs a small perfumery, 4160 Tuesdays, where she and her team make and bottle all their fragrances by hand, then despatch them to specialist shops in Los Angeles, Seoul, Melbourne and Cardiff. In 2019 she set up the Scenthusiasm Slow Scent School, online classes and courses for everyone who would like to create aromas of their own. She has worked with London Transport Museum, Bittersuite, Google, La Nuova Musica and Perroni. She specialises in using period materials to capture the aroma of a time and place. Her book, The Perfume Companion, was published by Frances Lincoln in September 2021, with co-writer Samantha Scriven.

Featured image: Sarah McCartney