Animation as a Process of Witnessing Place

TT Journal, ISSUE 4, 12th September 2022

By Pamela Taylor Turner

This is a story that entangles the practice of animation with the sensing of – and being sensed by – Place. I use the upper case “P” to indicate the individual nature of a specific site and to acknowledge respect for all it holds. Animation in its various forms can enchant the viewer with motion, sound, materials and appealing imagery, as we’ve all undoubtedly experienced. The act of evoking motion in a choreographed space (animating) is a process through which an artist can evolve a relationship to “Place” and all it might reveal.

What is this Place?

My early response to wandering on Chapel Island was a visceral feeling of being unsettled. Following the main path that parallels the river through the trees, I arrived at an uninviting end; a tall fence crowned with razor wire that guarded an open, empty expanse of land. A sign made it clear that entry, while not possible, was forbidden. A black tarp contorted in the wind, caught on the fence. Nearby lay a fragment of a butterfly wing, unmoving amongst decaying leaves and grasses that were animated in the wind. Intrigued, I began my study.

The contemporary Chapel Island is part of the James River Park system, in Richmond, Virginia (United States). It is slightly east of the Chapel Island, or more often, Sandy Bar, found on maps from the 18th and 19th centuries. At the time of European contact there was a large flat rock that made landing canoes and then English boats easy. This was at the mouth of a substantial creek (Shockoe) that emptied into the river; the dynamics of the waters there formed the sand bar. This area was favored by the Powhatan tribe within the larger Confederacy of Algonquin speaking tribes and was part of the homeland of Pocahontas whose life story has been appropriated and re-storied in animated form.

English explorers stopped there in 1607, claiming the land with a cross; their westward progress was halted by the rocks and rapids of what we now know is the geological ‘fall line’. The creek, the rock, and the sandy bar have long disappeared.

How do I learn about and connect to this Place?

I stepped onto this land with a sensitivity encouraged by an ongoing engagement with terrapsychology. This supported my intuition and inclination to dig in and to pay attention to the land itself. Terrapsychology, as described by its founder Craig Chalquist, “… is the field of imaginative studies, ideas, and practices for restorying and thereby reenchanting our relations with the world, with each other and with ourselves. It is a deep psychology not only of humans but of everything we interact with. It aspires to be a truly planetary psychology; for now, it is a psychology of reenchantment for living in an animate world. (Chalquist 27)” The process of this research, he explains, involves “…acquiring a set of extra senses attuned to the world’s speech” (Chalquist 5) Following that perspective, an integral part of my practice was paying attention with open senses, a commitment to wander and wonder, to witness and attend to this Place.

To witness takes time. The phrase “ongoing becoming” came to me through the writing of Monika Langer as a fitting alternative to the binary states of “being” or “non-being”. It speaks more holistically to the constant evolution of beings, from dragonflies to granite boulders, from humans to trees and rivers. “Being” is not static but has varying liminal states of transition. The river here is at the western end of the tidal waters as they meet the incline and energy of the rapids. The persistent tides, storms or “freshes” as they appear in written history, and the deep history of settlers unsettling the earth make it a potent place of change. To witness the ongoing becoming requires being with the mud, sand, trees, and stones, again and again. It shifts, I shift.

My understanding of witnessing and being with was significantly informed by Mary Watkins’ work in mutual accompaniment. “Accompaniment”, Watkins writes, “begins with stopping and noticing, crossing over the invisible lines that separate us, making time to connect, to understand, and to respond… It also crucially depends on understanding that as far apart as our individual fates seem from one another, they are ultimately intimately connected (Watkins ch. 1).” While here she is speaking of human connections, in her book Mutual Accompaniment and the Creation of the Commons, she includes a chapter on “Earth Accompaniment”, which applies these same tenets to the connection of earth, society and psychological crisis.

“Mutual” is a key concept here as the perspective and action is not from above or not imposed onto, but rather is alongside. There is a connecting to and learning from that requires commitment, care and labor. I go to the island at various times, temperatures, seasons and tides. I make texture rubbings, take numerous photographs and videos, touch the sand, the mud, and the water. I listen and pay attention, sensing what might come to mind, what might be revealed. The concept of reciprocity is key to this approach; it is interwoven in accompaniment practice, as well as ecopsychology, ecophenomenology and is a foundation in indigenous teachings. Witnessing and evoking through making art, is an act of reciprocity – as is picking up trash and keeping an eye out for the land in local politics.

The act of animating, the dance with Place.

It is the potential and potency held in the ongoing becoming that may be key to the intuited, instinctive sensing of significance we have encounter when enchanted. It also compels us to re-engage through animation. The act of animation aspires to evoke things in the varied states of appearing, moving, morphing and disappearing to somewhere else. Animation is change through time, morphing of shape through 490 years. As my process of witnessing progressed, the human history retreated and the place emerged. There were patterns in multicolored mud, leaves, tracks of people, herons, the shoaling of water in ripples and waves, and large turtles sunning themselves where water became sand.

In the studio we re-sense the feeling of Place – the verb-ed tense of air, mud, sand, light and water, the forming that is in process – and the ‘feeling’ held there, also shifting. It is a sort of dance with Place, a performative empathy with the living held there as we aspire to evoke in animated form. Through this material practice of animation, we look closer and consider the ‘in-between’, that liminal space of being, becoming, here, now, then, and there.

Stepping onto the island is an integral part of my practice, as I ‘re-tune’ in order to ‘attune’ to the place as it is in the process of being. As David Abram makes clear in his writing, I remember that I am also being sensed. In the notes I took there and immediately after my time there, I see a shifting to a “verbed” perspective, which guide me in my studio: push, pull, ripple, topple, hold, release. This resonated with a passage from Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teaching of Plants. She recounts her frustration – and eureka moment – as she is struggling to learn her native indigenous language, Potawatomi. Things she knew as nouns kept appearing as verbs. Then, reading the native word “bay” she suddenly sensed the being of a bay. She explains, “A bay is a noun only if the water is dead… trapped between its shores and contained by the word. But the verb…’to be a bay’ – releases the water from bondage and lets it live. ‘To be a bay’ holds the wonder that, for this moment, the living water has decided to shelter itself between these shores, conversing with cedar roots and a flock of baby mergansers (Kimmerer 55).” Understanding the river as being a river, the sandy bar in the process of shifting and barring is to engage in the animus of the world. Verbs, the being, the act of being, is inherent, of course, to the practice of the animator.

This idea of the verb, the becoming, is echoed in Paul Klee’s Notebooks Volume 2: The Nature of Nature, as he encourages us to “… think not of the form but of the act of forming (Klee 67).” Animation frees us from the pressure of that final ‘form’, a static, singular thing, pulling us instead to the ‘beingness’ of the thing. Considering the more-than-human, as well as the human, in a state of becoming is likewise helpful in the practice of animation and being with Place. The various ongoing becomings give guidance in the ‘re-storying’ of Chapel Island.

That initial feeling of being unsettled, of something not being what it thought to be, sent me to search for clues in maps and reports, undertaking a study that is much like that described as “a forensics approach to animation” by animator and scholar, Dan Torre. This approach, as he writes, “…suggests that through careful analysis (and the processes of animation), we can determine how presently immobile things might have previously moved or evolved as well as their potential for future movement. On one level this approach will provide an alternative close reading of the animation process; on another level it suggests that animation may be used as a vital epistemic tool for the direct discovery of new knowledge (Torre 206).” This way of considering things acknowledges that they are not only what we see at that particular movement; if we look closely, or put them in motion, we may see evidence of what they were, what they are, and what they are continuing to become.

Studying historical maps and tracing the changing shape of the ‘sandy bar’ over time, made it clear to me that human hands, settler hands, drew these maps with attention and intention on property rather than seeing the landscape. They were planning a place, not acknowledging the Place that was there. Drawing the forms found on the maps trains my eye, and my mind, to seek vestiges of those contours when physically present with the island. My initial unsettled feeling becomes clear through this process; the island is a liminal space, in an ongoing state of becoming through time, forming and being formed by the water, storms, and by human industry. What we call Chapel Island is not an island; it is connected to the mainland at its western end. The broad expanse of grass and concrete enclosed within the fence that takes the larger portion of the “island”, is a stormwater retention area, with catacombs of water underground. That is the closest physical location to what was once the “Sandy Bar”. What we now see labeled Chapel Island would have been Stegar’s Island, and then reshaped, along with Chapel Island, and made into docks for the canals, then the city docks, and then a shipbuilding yard.

Knowing this complex evolution freed me to discover the ‘real’ Place, unhindered by human historical story. I borrowed water, sand, and mud from the island as well as items left there by humans. A key point from phenomenology as voiced by Edmund Husserl that continues in ecophenomenology, is the getting to the thing itself – sensing through the body and intuition. There is a care not to intellectualize or mimic but rather to evoke or emote. This ‘loosening of the senses’, especially turning towards the invisible, the sensed, is addressed throughout David Abram’s work. He refers to “… the participatory sentience of our bodies” and “….and empathetic discernment…” These are important touchstones while on the island, and also when in the studio. It is easy to become distracted and deflected as “cool things” happen under the camera! Early in the project, I was fascinated by the dots of the ‘sandy bar’ map and played with those under the camera, having them run around the shape of the island. While fun, it felt, fake. Nothing was ‘speaking’ through the animation. This re-tuned me to looking at the land and realizing the dots indicated the sand revealed at low tide; suggesting a significantly different animated movement.

There is the study of water in motion that is particular to place, because of the tides and the density of the sandy, sedimented soil and why water curls on itself at that point here and not over there. Shoal, shoaling, the shallowness returning in places, the waters gathering playfully over the hidden sands.

I photograph sequences and assemble the still images in the computer, to study the captured motion, the formations that move so quickly, the light, and the movement of particles or things in the water. Drawing and painting requires a more embodied labor. Birgitta Hosea writes, “Drawing uses tools that extend the artist’s body and materials that mark a residue of the trace of an action. ….. Drawing is a record of time or endurance, a transaction, a trace of presence or touch, a ritual, a performance, a map, a form of meditation, of understanding, of thought made tangible (Hosea 365-366).”

Working with black walnut ink, water from the river, gesso and drawing, I, as animators must do, envision the water, feel the motion. I paint, move ink, and record frames. I review these studies, I go back to the island, more acutely tuned to see the movement there.

This process also requires letting go of the need to ‘get it right’; it is simply about ‘getting it’ in the broader relationship. Various art practices, and innovations, are engaged including stop motion of things under the camera, painting, drawing, digital effects, video, photographs, and printmaking.

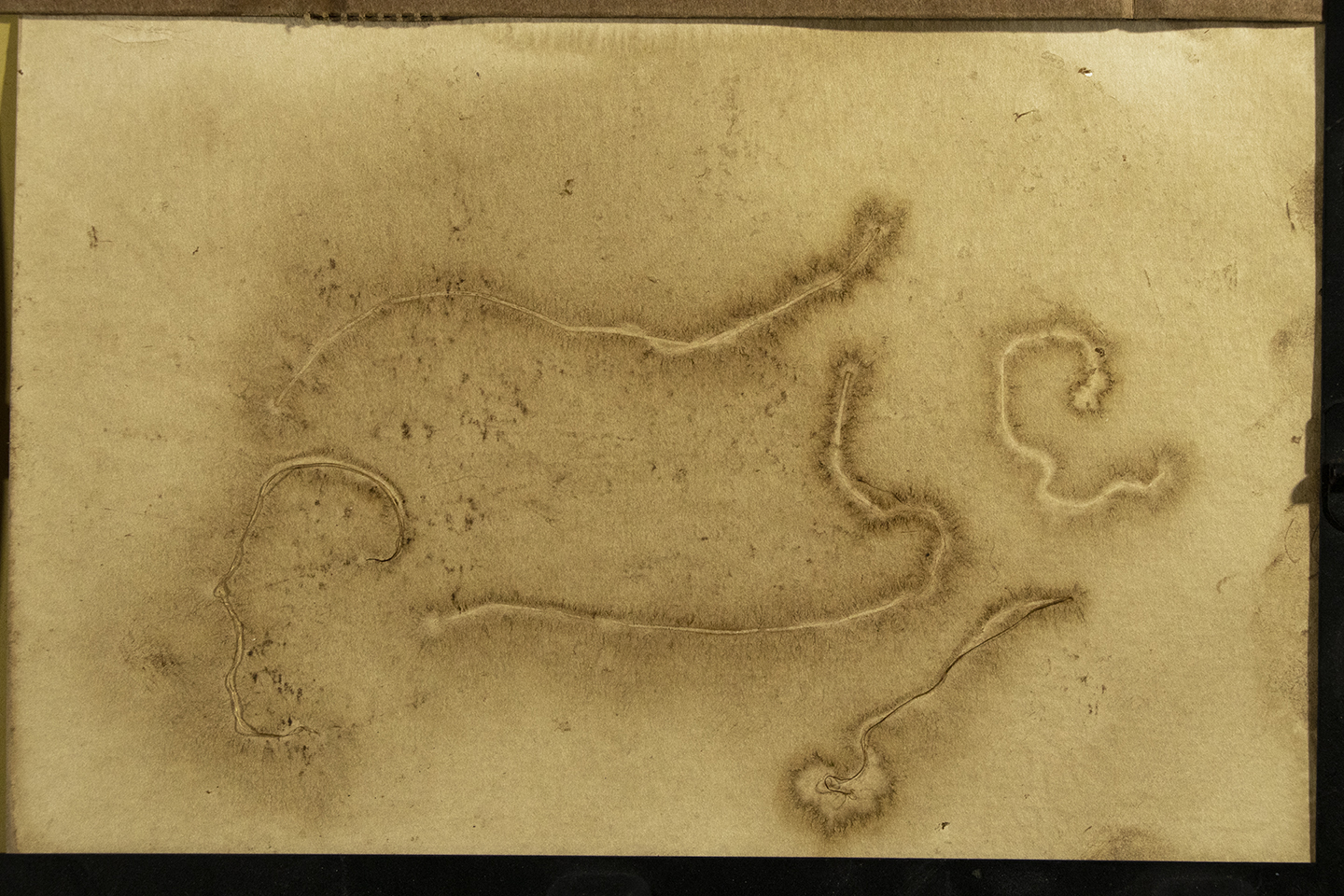

One ‘study’ is of the trails left by the Eastern Mud Snail. An unusually low tide transformed the river into an incredible expanse of sand bar and there I found scribblings in the sandy mud. In my studio study I chose not to replicate the paths but rather to evoke the wonder (and wander) of the paths themselves. I considered the push through the sand, the scale of the grains being like rocks to the small snail. The process of eating miniscule particles, attention to staying in the water, of diving down, of leaving a trail. With attention to process and pushing, leaving, drying, I laid corn silks on paper soaked with black walnut ink to make prints. The silks pushed the ink from the paper, the ink congregated on the outer edges of the silks. The resulting line held a similar fascination as the snail trails.

In his book, Terrapsychologocial Inquiry, Chalquist observes, “Those who practiced and played with the methodology gradually evolved it beyond a central focus on place to add the felt presence of other aspects of the material world: how weather and climate patterns, insect and animal movements, plants and stones, elements and mountains and bodies of water, and even cities, bridges, neighborhoods, and everyday objects get into us psychologically. We move, feel, and breathe to their contours, their textures, and their cycles without knowing it. But we can know it (Chalquist 3).”

Evolving onwards: outcomes of study

Mediated through animation processes in the studio, the relationship with Place and its ever- changing aspects has evolved from stranger, to familiar, to familial. Land that once unsettled me, now enchants me. To enchant, to cast a spell, comes from to sing onto, or perhaps into and I think of the sound of the cottonwood leaves, the ever-present freight trains, a heron’s squawk, Osprey screes, and the splash of water cascading through the culvert into the cove.

In this work, as in the work of accompaniment, there is a quiet activism. While I have become enchanted, the question is what form might this take to enchant others with the story of this Place? The animation in progress is an experimental/experiential ‘structured’ piece, with parts being developed for augmented reality experiences. These will focus more closely on moments of ‘ongoing becoming’ for the solo viewer to sense and witness. I aspire for the work, in its various forms, to evoke Place unburdened of its settler-ed and now clearly inaccurate name, experienced as it is, a verbed, always becoming Place.

Works cited:

Abram, David. The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-than-Human World. eBook, Vintage – Penguin Random House, 2017.

Chalquist, Craig. Terrapsychological Inquiry: Restorying Our Relationship with Nature, Place, and Planet, Routledge, New York, London, 2020.

Hosea, Birgitta. “Drawing Animation.” Animation: An Interdisciplinary Journal. 2010;5(3):353-367. doi:10.1177/1746847710386429

Kimmerer, Robin Wall. Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants Minneapolis, Minnesota : Milkweed Editions, 2013

Klee, Paul. Notebooks Volume 2: The nature of nature. Translated by Heinz Norden, Edited by Jurg Spiller. George Wittenborn, Inc, New York. 1970

Langer, Monika. “Nietzsche, Heidegger, and Merleau-Ponty: Some of Their Contributions and Limitations for Environmentalism.” Eco-phenomenology: Back to the Earth Itself, ed. Charles S. Brown and Ted Toadvine, State University of New York, 2003, pp. 103 – 120.

Torre, Dan, Animation – Process, Cognition and Actuality , Bloomsbury Academic, NY 2017

Watkins, Mary Mutual Accompaniment and the Creation of the Commons “Earth Accompaniment: Standing with Trees, Waters, Mountains, Earth and Air.” eBook, Yale University Press, NewHaven, 2019.

Extended bibliography: (not appearing in paper directly but influential)

Abram, David. Becoming Animal New York: Vintage – Penguin Random House, 2010

Barnhill, David Landis, ed. At Home on the Earth: Becoming Native to Our Place, a multicultural anthology 1999

Bennett, Jane. Enchantment of Modern Life 2001

Bennett, Jane. “Systems and Things: On Vital Materialisms and Object-Oriented Philosophy“, in The Nonhuman Turn, 2015

Buell, Lawrence. Environmental Imagination. 1995

Chalquist, Craig. Terrapsychology: Reengaging the Soul of Place. New Orleans: Spring Journal Books, 2007.

Fisher, Andy – Radical Eco-psychology: Psychology in the Service of Life 2nd edition,State University of New York (SUNY) Press, Albany, 2013.

Fisher, Philip. Wonder, the Rainbow and the Aesthetics of Rare Experiences, 1998.

Ingold, Tim The Life of Lines: World Without Objects. Routledge, 2015

Landes, Donald A., translator. The Phenomenology of Perception. By Maurice Merleau-Ponty New York: Routledge-Taylor & Francis Group, 2012.

Marietta, Don E., “Back to the Earth with Reflection and Ecology”, Eco-phenomenology: Back to the Earth Itself, ed. Charles S. Brown and Ted Toadvine, State University of New York, 2003. P 121 – 135.

Wood, David, “What is Eco-phenomenology?” Eco-phenomenology: Back to the Earth Itself, ed. Charles S. Brown and Ted Toadvine, State University of New York, 2003. P211 – 233.

Pamela Taylor Turner’s animation practice explores and interrogates the intuited connection to, and experience of, the more-than-human world. Her scholarship is in the history and practice of animation, following connections to visual effects, abstraction, phenomenology, animism, and new media practices. She is the biographer of the late animator Adam Beckett (Infinite Animation: The Life and Work of Adam Beckett, CRC Press, 2019) and serves as the Chair of the Board of Directors for the Society for Animation Studies. An associate professor in the department of Kinetic Imaging at Virginia Commonwealth University, she teaches courses in expanded animation, theory and history. She has certificates in Ecopsychology and in Enchantment from the Retreat at the Pacifica Graduate Institute. pamelataylorturner.com

*

Pamela Taylor Turner’s article was originally presented as a paper during Ecstatic Truth VI, an annual symposium dedicated to expanded animation and documentary (conceptualised very broadly as non-fiction), with a particular interest in the questions raised by experimental and practitioner perspectives. The theme of the 2022 symposium, which took place in Prague and online, was To Attend. You can also see the full recording of the programme here: