TT Journal, ISSUE 5, 20th January 2023

By Maya Gratier and Noga Arikha

“And because the stories were held here in fluid form, they retained the ability to change, to become new versions of themselves, to join up with other stories and so become yet other stories; so that unlike a library of books, the Ocean of the Streams of Story was much more than a storeroom of yarns. It was not dead but alive.” Salman Rushdie, Haroun and the Sea of Stories (Granta Books, 1990)

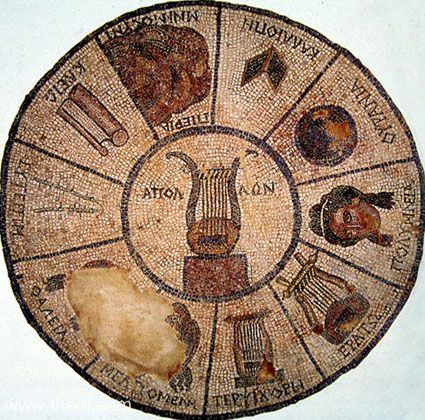

Humans have always been a story-making species: to engage in narrative is natural to us, and it is the bedrock of cultural invention. Stories are much more than entertainment. They are so present in human lives that they are found in the myriad forms of fiction that compellingly draw us into their worlds, in everyday conversations with neighbours or friends, in marketing tricks and strategies and even in our most level-headed scientific theories. They define who we are as individuals and communities within our unique histories. They are a currency that can be shared across personal, temporal and spatial boundaries. A force for growth and transformation, they constitute the testing ground for scenarios of our possible futures, as individuals, cultural communities – and as a species.

Never before, though, have we been able to tell and expose ourselves to so many stories, so quickly, and so widely. We live in an age of accelerated and disembodied communication. Every day, technology allows individuals constant access to a plethora of overlapping stories that recruit our attention, emotions, and senses, in diverse registers, and with split-second reactivity. Ours is a cacophonous world, where the thread of a single story is at once potent and fleeting, at once engaging and distracting from other stories – akin to the world described by Salman Rushdie in Haroun and the Sea of Stories, where a boy sets out on a mission to revive the well-spring of all humanity’s stories, which has been poisoned. And we believe that there is a connection to be drawn between the cacophony of stories that is criss-crossing the globe and the growing crises affecting the well-being of humans and all other animals. For that most cultural and human of activities begins within our very organism. Stories are cultural artefacts, but they emerge out of our biology, and are based on the innate capacity for narrative that we share with non-human creatures.

We would like to bring the notion of narrative into the very understanding of an embodied sociality and the development of consciousness. Narrative is distinct from story-making: it precedes speech, and is available to humans at the earliest stages of ontogeny. It is rooted in an evolved physiology common to all creatures endowed with a nervous system, so it is not even exclusive to humans. Narrative is from the get-go a relational activity, a generative impulse expressed in the agentic movements of any body acting in coordination with its environment, including conspecifics and other animals. It is a biological process built into the nervous system, and consists in the generation of internal images, visual, tactile, olfactory and auditory, embedded in a situated sensorium and allowing for responses to environmental events. Stories grow out of a narrative awareness that is the locus of language-independent meaning-making. Narratives are what humans make when they are together, with their hands, voices, faces and limbs, from birth onwards.

In this sense all stories are narrative since they relate to the narrative impulse we are born with as infants. But not all narratives are stories. Narrative is inherently based on a temporal sequencing of action, connecting present, past and future in a complex causal chain that corresponds to the meaning-making essential to our sense of self. This sense of self is constructed in relation to the non-self, out of interoceptive and exteroceptive processes – that is, out of the sense of the body from within, and out of sensorially mediated inputs from the outside world. The narrative that underpins meaning-making also organises feeling, in a weaving together of inward and outward rhythm, of interoception and exteroception. All animals have feelings that shape their actions and inform their nervous systems for the anticipation and control of their future-oriented movement. For humans, awareness of those same feelings and of how they affect the body constitutes consciousness. Consciousness and feeling are never disconnected, except in severe mental and neurological disorders.

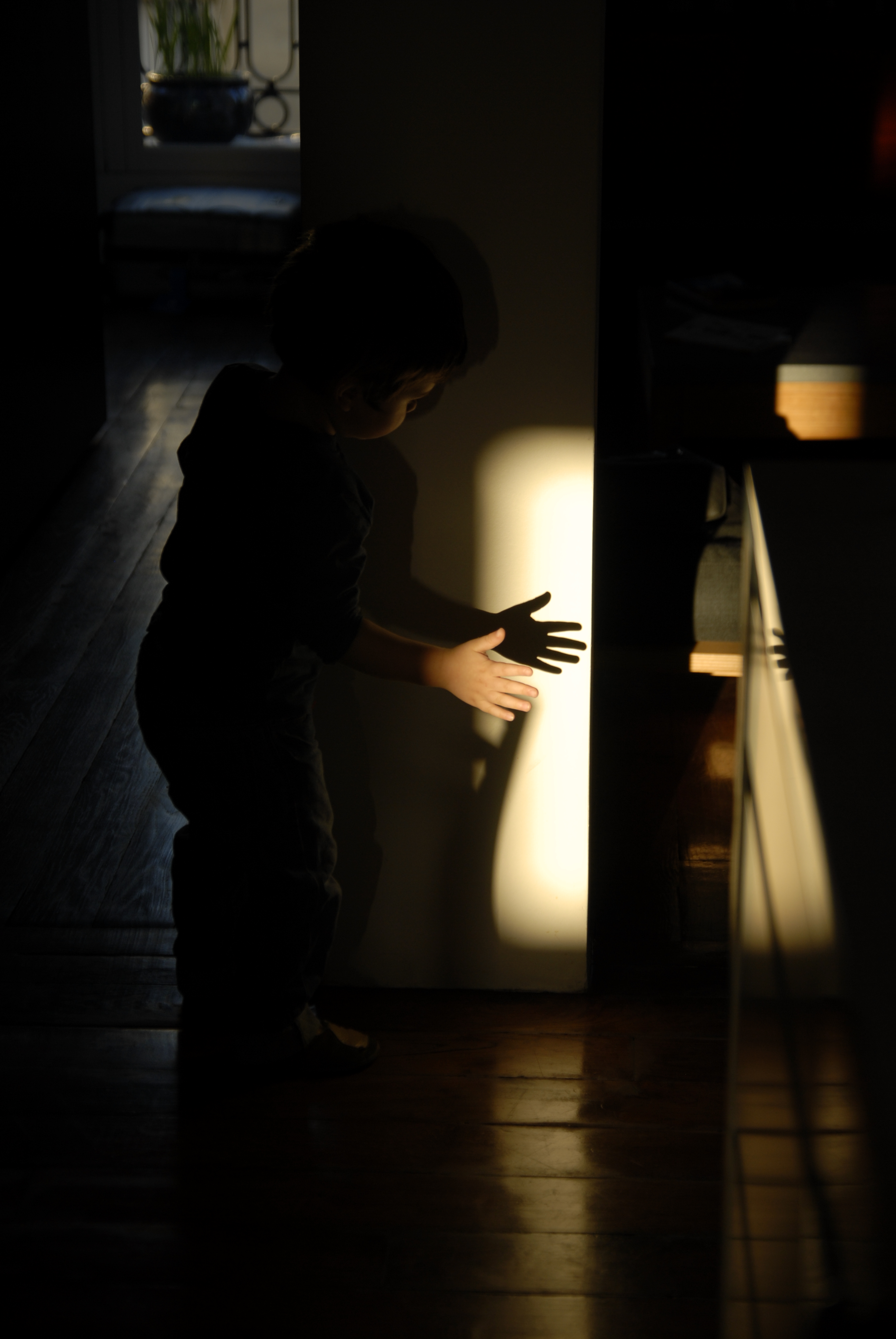

In infancy and before the mastery of language, humans have to be vividly attuned to their environments and in particular to the people who care for them and protect them. This is due to an unusual condition within the animal world of extreme neoteny. Infants are endowed with sharply perceptive senses that work together in holistic ways by picking up on regularities and correspondences, especially in the social environment. The predictive and associative brain of infants makes them participants in meaningful and meaning-making worlds where other humans become intuitively involved in the narrative body movements they perform through orienting, seeking and soliciting actions. Their interoceptive processes are shaped through their relation to their carers, without whom they cannot engage in the homeostatic regulation that underpins these processes. Infants thus have a quality of presence and attention that is rare among speaking adults.

Language is what enables the shift from narrative to story, and in so doing it fabricates other worlds with their own temporalities and presences that co-exist with the here and now. Language has the power to make the non-present world vivid without the energy-consuming reliance on an active and connected sensorium. It is highly adaptive, of course. It is the yarn with which we spin stories that, like a spider’s web, can exist on their own, becoming units whereas the worlds we inhabit with bodies and senses are continuously flowing and changing within vast networks of interdependencies.

When we use language, much of our sense-making comes from a narrative process which is entangled with story-making. We speak with our bodies as much as with our words, our voices and gestures perform the meaning our words do not tell. Such embodied narratives are always relational, but they do not rely on such symbolic language for sense-making. The body movements of infants, made through coordinated and controlled use of muscles evolved for expression of feeling and emotion, enact shifts in other persons involved with their needs, well-being and cognitive appetites. People move and talk in synchrony with infants, performing an improvised dance of togetherness within which consciousness takes form. Narrative, in this biological sense, is a dialogical process. It unfolds in shared time and its unfolding enacts changes in all parties involved in its making. Narratives feed the relationships that constitute us.

In infancy, what we call narrative is the framework that contains and regulates emotions and feelings, progressively building meaning. The expressive sequences of movement and sound characteristic of infants form repeated and varied patterns. Our emotional engagement with the world as adults arises initially out of this patterning: it is an outcome of the to-and-fro we experience at the beginning of life between new and known, familiar and unexpected, shaping memory, habit, and some personality traits. As infants, our minds continually seek out both familiarity and novelty: we live on the edge of the unknown and are drawn to discovery. The infant’s curiosity-driven expressions are inherently narrative because they build on recently acquired and socially distributed patterns and habits that we enact with attentive others in order to make ourselves understood.

Throughout life, a narrative involves a physiological shift in homeostasis. It may involve a quickening of heart-rate or increase in cortisol. All external events affect the internal, interoceptive processes underpinning homeostatic regulation. Homeostatic processes are faster and shorter in infants than they are in adults, especially in the early period of life. As we grow older, the narratives we participate in grow longer. By adulthood, we can follow a long story or play despite interruptions in its telling, maintaining homeostatic regulation, and resuming the emotional states and corresponding physiological shifts where we left off. As attention to inner processes, interoception is an inherent part of narrative, played out inside as much as outside the body. To experience a book, and make sense of it, is partly a function of how the book affects our bodies. That is why reading is so entwined with the formation and drama of selfhood.

Our brains fabricate social meaning by putting events in relational and sequential order through prediction. As Siri Hustvedt has noted, perception of rhythm and anticipation are critical abilities for narrative-making. Out of the narrative sequencing generated by rhythmic, sensorial, preverbal motor programs, humans create meaning, cultural habits, formulae, knowledge and transmitted memory. Out of previous experience, emerges felt presence. This is the essence of story-making. Stories make, bend and hold time. They create a felt continuity of being, the persistence and reverberation of a self that knows itself as an ontological unity. They involve projecting a future that extends and becomes more predictable as habits and memories form. Memory feeds and overlaps with imagination: without memory, imagination is disabled. The future is never entirely new, since it is woven into the past, through the processes involved in story-making: we incessantly draw threads between discrete events and moments.

It doesn’t take much to tell a story – to identify, recognize and share discrete moments, and to connect them even when they are separated by gaps requiring cognitive leaps. A few signs strung in order become powerful conduits of the imagination. But stories can also be dangerous, insofar as they are attempts at capturing and preserving realities that no longer or will never exist, encapsulating time, compressing or prolonging it. They can distort experience by imposing a perspective, they can hold us captive and make us lose sight of ourselves. To enter a story is to live inside a temporality whose shifting qualities recruit the same cognitive capacities for anticipation and prediction that help us survive in the real world. Stories throw us into atmospheres that titillate our senses in imagined spaces without any tangible sensorium. The power of stories, like the power of pre-linguistic narrative, comes from their activating the cerebral and sensorial circuits for pleasure, reward and motivation.

With the growing speed and efficiency our digital technologies afford, the stories we make are indeed becoming dangerous. We are subverting our very capacity to make sense: we are disorientated and destabilised by the multiplicity, diversity and rapidity of the stories we are spinning within our overlapping and conflictual cultures. Perhaps, then, what we need today is to ensure that our cultural fabrication of meaning remain steadfastly rooted in that well-spring of embodied relational narrative which made us conscious, logophile and literate in the first place. By recognizing the special function of narrative in the lives of humans, from infancy onwards, we may be able to re-configure more benevolent and adaptive stories, and start creating a future that reconnects and resituates the human within its vital and complex interdependencies with all living creatures on our planet.

Noga Arikha is a philosopher, historian of ideas and essayist who works as a “science humanist”. Her The Ceiling Outside: The Science and Experience of the Disrupted Mind was published in spring 2022 by Basic Books (UK and US). She is also the author of Passions and Tempers: A History of the Humours (2007). She is a Visiting Fellow at the European University Institute in Fiesole, Associate Fellow of the Warburg Institute and of the Center for the Politics of Feelings (London), Research Associate at the Institut Jean Nicod (Paris), and Research Associate at the Fotopoulou Lab at UCL. Website nogaarikha.com

Maya Gratier is professor of developmental psychology at the University of Paris Nanterre in the Ethology, Cognition and Development Research Lab. Her research focuses on the development of face-to-face communication in early infancy and in particular by studying vocal coordination.