TT Journal, ISSUE 5, 20th January 2023

By Giuliana Bruno

To live is to pass from one space to another.

—Georges Perec

A window on the architecture of living opens with a paradigmatic series of paintings and drawings made by Louise Bourgeois, beginning in the early 1940s. Called Femme-Maison, they represent a woman in the shape of a house. In this “architexture,” the body and the house are joined in the itinerary of dwelling. In exposing this link, Bourgeois designs a haptic map of inhabitation, questioning what domus means for the female subject. Her work challenges the lost-standing association of domus with gender fixity. Instead, the drawings suggest that a woman can conceive of home as something other than an enclosed, and enclosing world. She can “suit” herself to a different image, explore the space of interiority, and even reclaim domesticity. She can opt for a “traveling domestic,” remapping herself in fluid notions of home. Here, this location is grounds for departure.

This is the retrospective voyage of a cultural hybrid. It is not by chance that Louise Bourgeois—a French artist transplanted in New York who, for sixty years, has mapped the architecture of the interior—included a map of her hometown in her autobiographical book of pictures, marking in red the itinerary of her travels within.[1] She inscribed a journey on her map of home, using a form of cartographic representation that goes all the way back to Madeleine de Scudéry’s Carte du pays de Tendre (1654), a map that visualized, in the form of landscape, a world of affects. An emotional journey is drawn in these maps of lived space. They show the motion of emotions that reside in-house. In this affective mapping drawn by women, home can indeed turn into a voyage.

Fashioning Lived Space

Bourgeois’s Femme Maison recalls a series of collages made between 1939 and 1949 by the Czech modernist avant-garde artist and writer Karel Teige. In Untitled from 1949, the torso of a woman is drawn as a house, which, in turn, becomes her spine. A view of the interior opens up when, in Untitled from 1946, a window opens into her body, making her able as well to look outside its confines. Most interestingly, in Untitled from 1948, a woman suits herself in a dress that is an address. She is dressed in a garment made of bricks that can curve and bend, softly suiting her body. The fabric of this apparel is a reimagined architectural fabrication. In Teige’s vision a wall of bricks can be a tessellated cloth, thus joining habit and habitation in their own tessellated construction.

These modern artistic visions address architecture in order to redress the house. They have inspired me in turn to explore the philosophy of dwelling, especially considering the relationality engaged in forms of inhabitation, in order to reconsider as well how sexual difference is housed. To look architecturally, and with geographical eyes, at the relation of private to public space is also a way to address the diversity of cultural landscapes in our forms of urban dwelling. This can lead to understand sexual difference itself in terms of space—as a geography of negotiated terrains. Thinking geographically, we can design different cultural maps as we venture into the terrain of interior space—the construction of lived space.[2]

Mobilizing gender positions in relation to the interior requires a series of displacements. Thinking as a voyageuse can trigger a relation to dwelling that is much more transitive than the fixity of domus—a site too often conceived in confining terms and confused with a constricting sense of domesticity. We need to engage in a constant re-drafting of the house, rather than staying within the circularity of origin and return, which is inscribed in the notion of oikos, as exemplified in the Odyssey. Rethinking the oikos as a less fixed and more fluid space can instead inspire a domestic cartography that is errant and capable of drafting the relational movements between interior and exterior. Imaginative as well as physical forms of wandering define this type of cartography, which is guided by a fundamental remapping of modes of dwelling. Such conceptual movement also ensures that spatial attachment does not become a desire to enclose and possess. A different idea of architectural voyage and different housing of gender can be projected in this way: travel which is not separate from dwelling. As in the architectural artwork of Andrea Zittel, here too, housing turns into deterritorialization, and can include a form of transito—a mobile map of dwelling.

Traveling Domestic

In redressing visual space, then, a reflection on cultural journeys leads not only to a different notion of urban travel but also to one of dwelling—one that takes into account the bodies that traverse the space. Opening the doors of public space to women, and rethinking the space of the city through gender has been the first step in this remapping of sites, and this subject became the focus of early theoretical studies of architectural space.[3] Engaged since the early nineties in such study of space, and especially interested at the time in reclaiming female flânerie, I have myself long argued for the mobilization of sites in relation to the spaces of female subjectivity.[4] In extensively traversing the urban space with renewed eyes, it then became apparent to me that the itinerary of the flâneuse had to be extended to the space of interiority. I felt the need to look more deeply inside the house of architecture, in order to mobilize it more intimately. Over time, then, this critical project has involved relating space, mobility, and gender to the transformations of visual culture, and their mediums, and drafting the emotion as well as the motion of lived space on these intersections.[5] This investigation has led me to realize how deeply entangled exteriority is with interiority, and how much technology transforms their borders. After all, intimacy is not a private notion but one that circulates in—and affects—the public sphere. And it is a modality that shifts and moves as much as exterior space does. It is in the space of interiority that real change, such as gender mobility, actually takes place. The house itself is not a static construction. It houses substantial movement. In its interior, different modes of subjectivity, sociality and commonality can be imagined, and their visions actualized. In this sense, it is important to look at art that represents forms of dwelling. As we pursue this design of further connecting architecture to art, and to the art of living, more fluid forms of becoming of the interior can emerge. Let us then move closer inward and explore the domestic as the place of what Elaine Scarry has called “the making and unmaking of the world.”[6]

Mediating Interiors

In the project of mobilizing the interior, and considering the house a site of travel, the writings of the architect Bruno Taut prove particularly illuminating. They do so especially as they engage dwelling itself as a moving form. Taut’s architecture, in fact, was important in the fashioning of gender on an interface that connects visual and architectural mediums. For example, in his 1924 book Die Neue Wohnung: Die Frau als Schöpferin (The New Dwelling: Woman as Creator), Taut asserts that it is a woman’s way of inhabiting space that creates and modifies architecture.[7] Her reception of space has an active role in its construction, as he shows, comparing architectural drawings to painterly renderings of interiors, thus intertwining the history of art with that of architecture.

To consider the input of the modern woman to the public making of private space is a crucial step in the mobilization of gender positions. Here, Taut makes an important contribution when he points out that architecture is made by way of using it. Speaking of women’s use of architectural space as an active function, Taut touches on the birth of the female public. His architectural study programmatically addresses the new fashioning of female subjectivity as public.

Acknowledging women’s role as shapers of space, Taut speaks of mobilizing the environment. He designs a mobile home, one in which all trajectories are streamlined and rationalized to release women from domestic chores. Carefully outlining all movements that take place in the house, Taut works at making the new home an equivalent of fast, modern travel. This equation between house and travel is literally rendered in drawings that map in-house journeys. In these architectural designs, the architect charts a new home for the new woman as a transformative object. In Taut’s view, modern architecture actually ends up becoming a means of transportation.

This mobilized architecture is equated to another wearable art of the everyday: fashion. Speaking of the ideal form of habitation, Taut compares the house to a piece of clothing, and quite literally, calls the house a woman’s dress. Does this scenario expose a conflation, the suiting of house and woman? In a design that is close to the dwelling voyage of Bourgeois’s Femme Maison and of Teige’s collages, the architect’s “house dress” turns out to be a means of travel:

[Designing] the ideal house . . . we must reach an organism that is the perfect dress, one that is to correspond to the human being in her most fertile qualities. In this respect, the house is similar to clothing and, at a certain level, is its very extension. Fertility and human creativity reside, now as ever, in transforming things. Today, we find visible signs of these changes in all those phenomena that until recently did not even exist, that is, the industrial creations. They have already transformed our every-day life, and they will transform the house. This is evident if we observe the means of transportation, that is, cars, airplanes, motor boats, ocean liners, trains, and if we fully comprehend the extent of revolutionary inventions whose possession has become indispensable to us: things like the telegraph, the telephone, the radio message, electricity, all the applications of the motor, to which we must recently add the increased manipulation of water and wind, and the stove. [8]

In this modern physiognomy of architecture, the house travels. It does so, and much before the digital age made the exterior world flood into the interior. Considered from my angle, this mobile home is already a mediatic space. In modern architecture a home is in fact already associated with means of transportation and communication. And it is the kitchen that is at the heart of a social transformation that involves technology. The stove is like a telephone or a telegraph, and can even send radio messages. Its “motor” is a technological motor, a mechanism as fluid as water and as fast as wind. This modern home is a real haptic and energetic dwelling-place, full of means of transmission and currents of electricity. Such mediatic space even resembles a movie house. After all, this is itself a home of mechanical organisms and a host of technological apparatuses. Moreover, this traveling home is not only a moving entity but a removable one. It is equated to a dress that can be changed, and equipped with epidermic qualities. This house shows its wear, just as skin, cloth and pellicule do. It wears its history in its texture. As such an extension of our modern bodies, this (movie) house is a special dress: its fabric is a complete mediatic fabrication.

Although Taut himself does not make the connection between the house and the movie house, and does not even mention the cinema among the means of transport and communication that he equates with new forms of urban domesticity, his very cinematic language triggers my interpretation. The moving image suits his model. Taut’s argument easily extends from the house to the movie house, for it touches new ways of fashioning space and creating new sites of mobility by means of technology. This cultural shift binds architecture to film as mediums of modern life. A new territorial fashion was taking place in both spaces of modernity, one that was changing socio-sexual roles. The female public of the house of moving images was indeed addressing new forms of fluid intersubjectivity. A space of public intimacy was set in motion.

Traveling-Dwelling

This modern shift to mediatic forms expanded the horizon of domesticity: “Now, Voyager,” a woman could travel in-house in forms that are mobile. Mobilization could be extended from the public to the domestic realm, exploding its private borders. Redrafting the architectonics of home, a different, mobile mapping of urban space could begin to be designed. Following this path, in recent times, one can see such form of architectural thinking actualized in the visual arts. A new concept of home is visualized in contemporary art, where the house is insistently redrawn. This is the case for Toba Khedoori, an Australian-born artist who lives in Los Angeles. Khedoori’s large elegant paintings on waxed paper tour dwelling insistently. They depict façades of houses, cross-sections of interiors, windows, hallways, stairs, walls, doors, railings and fences. Their subtle intervention on housing travels the architectural path of Gordon Matta-Clark and takes it into new realms, contributing moving views to the analysis of dwelling. The architectural fragments—remnants of an architectural dissection—are metonymically related to the moving image. These fragments of an architectural montage picture a sequence of film frames. Kedhoori’s floating world suggests that a mobile map of traveling-dwelling engages the language of media, and this creates a transformation that is signaled in the arts.

In art as in theory, setting in motion real transformation necessitates a repositioning of all senses of dwelling. Rather than merely addressing the urban exterior as mobile, we should indeed continue to pay more attention to the interior as a space of substantial mobility. No longer the spatial antithesis of urban travel, the house, as the dwelling-place of home, can lead us to theoretically construct a more fluid and shifting sense of boundaries. If we roam about the house architectonically and with traveling eyes, through the lens of various visual artworks, we will discover a profound liminality. The house is a threshold, a site of traversal of subjective, mental, emotional and social forms, which in turn transform them. Think, for example, of how the video artist Gary Hill has conceived the house in terms of material space. His house is one in a series of Liminal Objects (1995-onward), traversed by such lived matters as brains, which constantly change its perspective. In turn, mental matters such as mentalities are modified in the act of domestic traversal.

Drawn as such a liminal object, the house thus becomes the center of our tour. As we stroll around the house and refocus it, we may also follow the architectural/photographic path traced by Seton Smith, a New York artist that has long lived in Paris, and question, as she does, the idea that Five Interiors equal Home (1993). As in Smith does in her series of photographs of Interiors (1993), we may wish to approach our interiors as out-of-focus spaces. In such a way, we may position ourselves on staircases, reviewing architectural fragments such as beds, cradles, and gowns, or see ourselves through a “distracted mirror” that reflects doorways. We may find ourselves on thresholds in front of oblique compositions and address mirrored mantle-pieces looking up at a ceiling. We may choose to sit in skewed cornered chairs, face re-framed windows, or travel in soft focus along any of the home passages. As we shift our focus in this way onto the various forms of traveling domestically, let us direct our lens at some other stories of interior design, in the vital hyphen between the architectural wall and the mediatic screen, where domestic transport takes place.

House as Airport: Bedroom Stories

The type of displacement that we have theoretically evoked constitutes a terrain of artistic mapping for Guillermo Kuitca, an Argentinian artist of Russian Jewish descent whose bedroom stories make up a fascinating, errant cartography. Kuitca travels the domain of the Carte de Tendre, working, delicately and sensuously, with architectural methods and geographic imagery. These include the floor plan of an apartment and maps. Kuitca’s road maps, regional charts, architectural designs, urban plans, blueprints, tables, and genealogical charts radiate from Buenos Aires but speak beyond its borders. The artist has inventively charted space and reworked maps of existing cities or countries, imaginatively exploring their topography. He has also made maps of people in the form of genealogies and family trees, and charted relations and connections between human beings.

In Kuitca’s work, the veinal cartographic grid is subject constantly to retraversal and internal movement. A path may be stained with paint, red as blood, as if to mark a painful passing. Names of cities from different countries may be interpolated on a single road map, creating an imaginary topography. In the fashion of a film spectator, the viewer of Kuitca’s maps is asked to retrace a narrative trajectory and interpret its journey. Along this route, uncanny things may happen. The name of a city may be inscribed, over and over again, on the same map. Showing how an entire world may be reduced to a single place—the site of unavoidable destiny and inevitable destination—Kuitca reveals the obsessional nature of our emotional geography.

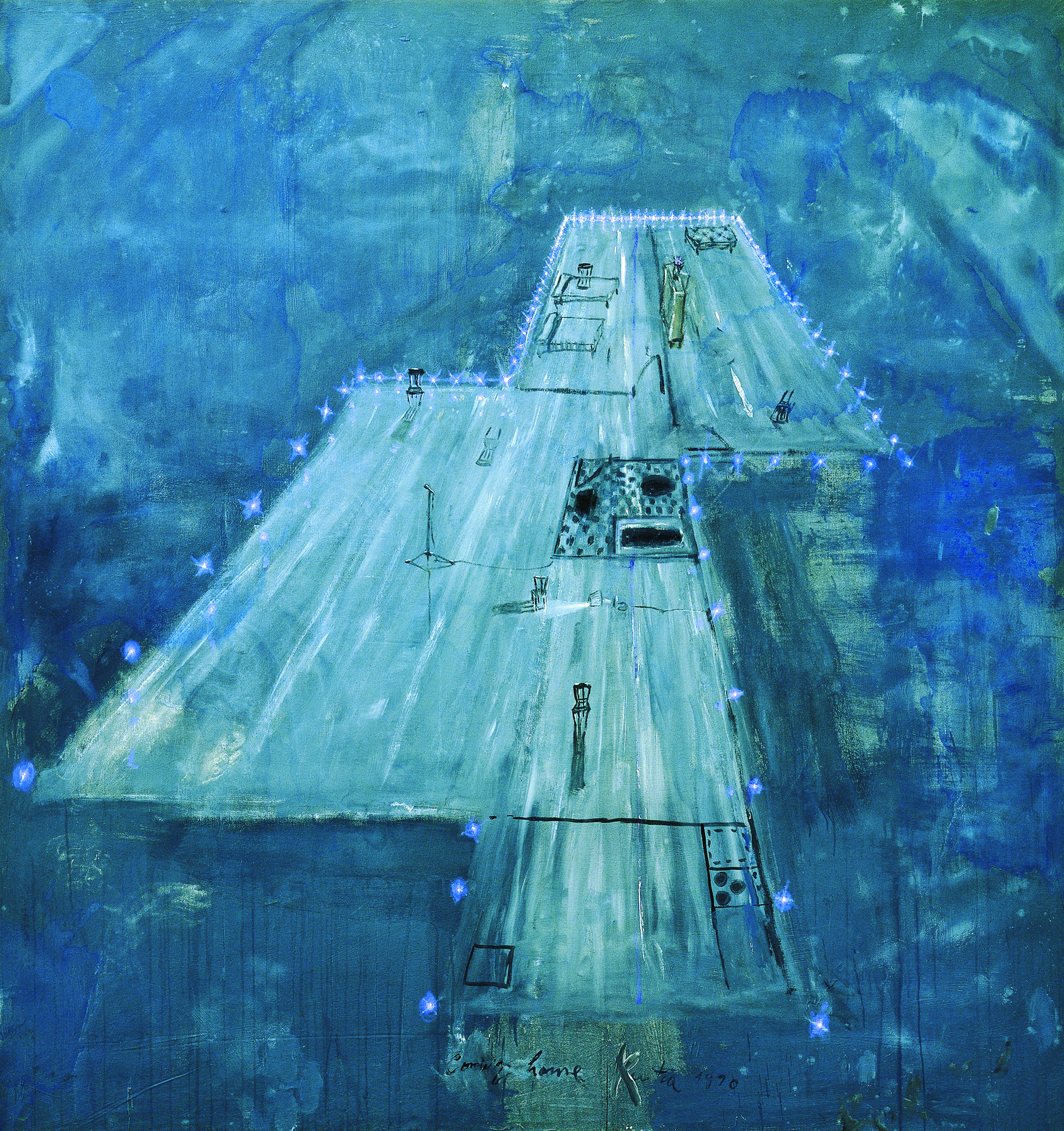

In his tracing of history and loss, the artist travels domestically. This journey becomes a stunning map in Coming Home (1989), a painting in which an apartment plan is designed to look like an airport landing strip. Here, traveling and dwelling are totally fused in one single map. The domestic ground turns into a plane field. In Kuitca’s work, we always land in this place of coming and going, even beyond his exemplary rendition of the house as an airport. The floor plan of what is essentially the same empty apartment is endlessly retraversed. As in House Plan with Broken Heart (1990), House Plan with Teardrops (1989), or Disposal House Plan (1990), for Kuitca, home is a particular architectural landscape: a physiology designed by the trajectory of relations and emotions. Architecture incorporates and expels. It is a melancholic fragment. Kuitca’s homes cry, bleed, secrete, defecate. In Union Avenue (1991) this “inner” working of urban planning is charted as an interior design. Here the lines that mark city blocks are made of forks, knives, and spoons. In such a way, the map recreates the geometry of the domestic. This is a plan of familial topographies. In his mappings, Kuitca has also used thorns and bones as the delineation of architectural edges to reveal the true perimeter of his mapping and to suggest what the border actually contains and releases.

Kuitca’s architectural views map a world of daily objects. Like the passengers in the films of Michelangelo Antonioni or Chantal Akerman, in Kuitca’s paintings we move between a bed and a chair. But, most of all, we travel on a mattress. Kuitca’s most evocative landscapes are bedroom worldviews. These are imprinted in a number of works entitled Untitled, produced mostly in the nineties: matresses upon which road maps of Europe have been designed. In the installation Untitled (1993), for example, the mattress-map, repositioned sequentially in an architectural space, entices us to share a private bedroom fantasy. Lonely mattresses are scattered on the floor. The space is suspended and frozen. It is as if something has just taken place or is about to happen. No one is lying on the beds. But the maps are there to speak of a fiction—an arresting domestic tale. This is a story written on a bed, inscribed in the fabric of a room, layered on the geological strata of a used mattress, entangled in the buttons punctuating its surface. The map haunts the mattress like a stained memory. It is a residue, a trace, a living document. The mattress was a witness. It absorbed a story, some event—perhaps too many events or not quite enough of them. Now, inevitably, it recounts the tale of what was lived—or unlived—on it.

As if it were a film, the bedroom map retains and explores folds of experience. It charts the private inner fabric of a mental landscape. The mattress-map is a complex narrative: a nocturnal chronicle, an erotic fantasy, an account of the flesh. The road map of cities designed on a bed is a chart of phantasmatic life. It belongs to the realm of dreams and their interpretations. Reproducing the immobility that allows us to travel in the unconscious, it traces the very itinerary of our unconscious journeys. The mattress-map portrays the motion of the emotions. It is a life map. An anatomy of life, this is a relational chart—an actual map of relationality. It is an inhabited vessel, with roads that are veins and places that are belly buttons. Such a relational map, in which land is skin, retraces the layers of people populating our space and draws the places populating our peopled landscapes. It tells us that, in a kind of “mimicry,”[9] people themselves become places, marks and markers of our living map, just as our faces, decorated with the lines of memory, become the map of our passing.

Positioned in this private architecture, Kuitca’s residual cartography touches the living house of memory and dreams—the very cartographic debris that is the fabric of motion pictures. It charts the same haptic, affective space of the moving image while even retracing its mnemonic cultural journey. The cinematic aspect of Kuitca’s cultural mapping, in fact, is made textually explicit in his work. Eisenstein’s Odessa steps become the painterly scene of El mar dulce (1984 and 1985) and Odessa (1987). In Coming (1989), a story is mapped filmically in twelve frames, each containing a different angle of view. Somewhere in a city, there is a dining room, a bathroom and an empty bed. While apartment views appear in axonometric projection and ground plan, a diagram of street plans and regional maps resides in other frames of the painting, both locating and dislocating the viewers. The whole scene is stained by bodily fluids. Corporeal marks leave their impression in an empty, deserted bed, intractably painting a vacant apartment with the liquidity of love.

The range of Kuitca’s maps extends from a filmic form of storytelling to the architecture of filmic space itself. In the series of gigantic miniatures called Tablada Suite (1991-93), his art of memory becomes the intimate architecture of spectacle: the shape of puro teatro. It becomes spectatorial space, a site where, quite suitably, the archive and the cemetery are placed next to other theatrical sites of recollection. As they chart in this way the geography of relationality—the site of public intimacy and collective dreaming—Kuitca’s maps touch the very texture that has produced the space of the unconscious optics of film. Narrating the architecture of socio-sexual space, the maps inhabit the same intimate room of filmic matter. The house of moving pictures. The home of emotion pictures. Gigantic miniatures, indeed, in the collective cartography of recollection.

The Wall and the Screen, A Living Space

Like a film, the house tells stories of comings and goings, designing narratives that rise, build, unravel, and dissipate. In this respect, there is a tactile continuum—a haptic hyphen—between the house and the house of pictures. The public white film screen is like a blank domestic wall on which the moving pictures of a life come to be inscribed. Etched on the surface, these experiential pictures change the very texture of the wall. The white film screen can become a site of joy or a wall of tears. It can act like the wall envisaged by Ann Hamilton in her moving installation Crying Wall (1997). On its white surface, drops of feelings drip, seeping through, as if all bodily liquids were conjoined on the architextural surface. One can feel the pain that the surface bears. The film screen sweats it, like this artist’s wall. It holds it like the house’s own wall. The screen is itself a wall of emotion pictures, an assemblage of the affects generated in a relational space.

Remembered and forgotten, the relational stories of the house constantly unfold on this wall/screen. They are sculpted in the corporeality of architexture, exposed in the marks of duration impressed on materials, inscribed on fragments of used brick, scratched metal, or consumed wood, and, especially, in the non-spaces. They are written in the negative space of architecture, in that lacuna where the British artist Rachel Whiteread works, casting the architectural void of everyday objects, and the vacuum of the domestic space. The volumes of stories of her House (1993-94) become material once exposed in a solid cast of its hollow volumetric space. They continue in the discarded Furniture (1992-97) laid on the street, in the filled holes of a Table and Chair (1994), or the Amber Bed (1991). They show in the peeling wallpaper or the paint stain of the Rooms (1996-98), in the unfinished or about to be demolished Constructions (1993-98), in the space of the Closet (1988), and in another (in)visible Untitled (Room) (1993).

Transformed in this way, stories of relationality unfold on the surface of the wall/screen, changing the texture itself of these mediums. In Mona Hatoum’s work, the surface absorbs a specific moving design, which speaks of displacement. In the hands of this Lebanese Palestinian artist exiled in London, all marks that are made are constantly erased as if redrawn on the sand. Sometimes all that is left of the painful movement of displacement is a remnant—what she calls a Short Space (1992): hanging bedsprings, relics that speak of dislodging, the remains of diaspora.

In the hands of the Colombian artist Doris Salcedo, La Casa Viuda (I-VI, 1992-94) becomes, through the specific and traumatic historicity of her country, an “Unland” (the title of another of her pieces, from 1997). Her series of untitled furniture pieces (1989 to 1995) “testifies” to a violent history that came to perturb an intimate geography. An armoire (Untitled, 1995), laden with cement, makes this trauma visible through its glass doors. The folds of the garments that were stored there now seep through the porous texture of the cement. Held in this melancholic way, they have become further worn. By the force of this exhibition, which includes us as mourners, the work returns to us the very architexture of an intimate space, its fabric. A bed and an armoire can, indeed, be a ruin in the ruined map of one’s history—that map held by the house and traversed by the visual arts.

As it narrates in its own negative space diverse stories of intimacy, recording the movement of lived space, architecture adjoins art and film, acting as domestic witness. All function as a moving document of our dwelling. A site of traveling-dwelling, they design our lodging in space, and trace our passages in the interior. A map of cultural motion, this place of moving images is a shifting dwelling, the virtual trace of our haptic journeys. As in Kuitca’s house plan shaped as an airport, what becomes palpable in this design is our passing—the screen of our changing spatial historicity. There is a moving house in the movie house. It shows a moving lived space.

Notes:

[1]. Louise Bourgeois, Album (New York: Peter Blum, 1994). See also, Bourgeois, Destruction of the Father/Reconstruction of the Father. Writings and Interviews 1923-1997 (Cambridge, MIT Press, and London: Violette Editions, 1998).

[2]. For an introduction to social space as lived space, see Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space, trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith (Oxford: Blackwell, 1991).

[3]. See, among early studies, Beatriz Colomina, ed., Sexuality & Space (Princeton: Princeton Architectural Press, 1992); Diana Agrest, Patricia Conway and Leslie Kanes Weisman, eds., The Sex of Architecture (New York: Abrams, 1996); and Jane Rendell, Barbara Penner, and Iain Borden, eds., Gender, Space, and Architecture: An Interdisciplinary Introduction (New York: Routledge, 2000).

[4]. See Giuliana Bruno, Streetwalking on a Ruined Map (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993).

[5]. This project is articulated in my books Atlas of Emotion: Journeys in Art, Architecture and Film (London and New York: Verso, 2002), and Public Intimacy: Architecture and the Visual Arts (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007), from which this essay was adapted, on the occasion of an art exhibition. It was first published with the title “The Architecture of Lived Space,” in Temporary Structures: Performing Architecture in Contemporary Art, ed. Dina Deitsch (Lincoln, MA: De Cordova Museum, 2011). It is reprinted here in a revised version.

[6] Elaine Scarry, The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985).

[7]. Bruno Taut, Die Neue Wohung: Die Frau als Schöpferin (Leipzig: Bei Klinkhardt and Biermann, 1924).

On Taut’s role in the fashioning of modern architecture, see Mark Wigley, White Walls, Designer Dresses: The Fashioning of Modern Architecture (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1995).

[8]. This citation is taken from the Italian edition of Bruno Taut’s book, entitled La nuova abitazione: la donna come creatrice (Rome: Gangemi editore, 1986), 84-85 (my translation).

[9]. On this notion, see Roger Callois, “Mimicry and Legendary Psychastenia,” October, no. 31, (Winter 1984):17-32.

Giuliana Bruno is Emmet Blakeney Gleason Professor of Visual and Environmental Studies at Harvard University. Internationally known for her interdisciplinary research on visual arts, architecture and media, she has published seven award-winning books and over one hundred essays. Her latest book is Atmospheres of Projection: Environmentality in Art and Screen Media (Chicago, 2022). Atlas of Emotion: Journeys in Art, Architecture and Film (Verso, 2002) has provided new directions for visual studies and won the Kraszna-Krausz prize for best Moving Image Book. Her other boos include Streetwalking on a Ruined Map (Princeton, 1993), winner of the Society for Cinema and Media Studies book award; Public Intimacy: Architecture and the Visual Arts (MIT, 2007), and Surface: Matters of Aesthetics, Materiality, and Media (Chicago, 2014). Professor Bruno has written on art, among others, for the Guggenheim Museum, the Venice Biennale, the Museo Reina Sofia, the Whitney Museum, and the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). Her work has been translated into a dozen languages. Her many honors include a Fulbright and a doctorate honoris causa, awarded by the Institute for Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts.