TT Journal, Vol.1, ISSUE 1, 3rd November 2020

We live in a time of disintegration and deconstruction. In the furnace of the pandemic, many of our systems and structures are revealing themselves to be unsustainable, destructive or irrelevant. We are called to summon the powers of the imagination, both to enable the necessary deconstruction and dissolution of these systems as well as for the urgent task of reconstruction and reinvention of new systems, structures and processes.

But what kind of imagination do we need now? What powers of imagination? How we conceive the imagination and how it works is culturally determined. Not only do we need to reimagine our world, we need to reimagine imagination itself. The modernist version of imagination is individual, heroic and singular. The new, emerging vision of imagination is relational and reciprocal, collective and collaborative. In the midst of my career as a visual artist, I stumbled on a form of imagination that supports and embodies the vision of imagination as inclusive and relational. Even more important, it includes the ground of imagination: the body.

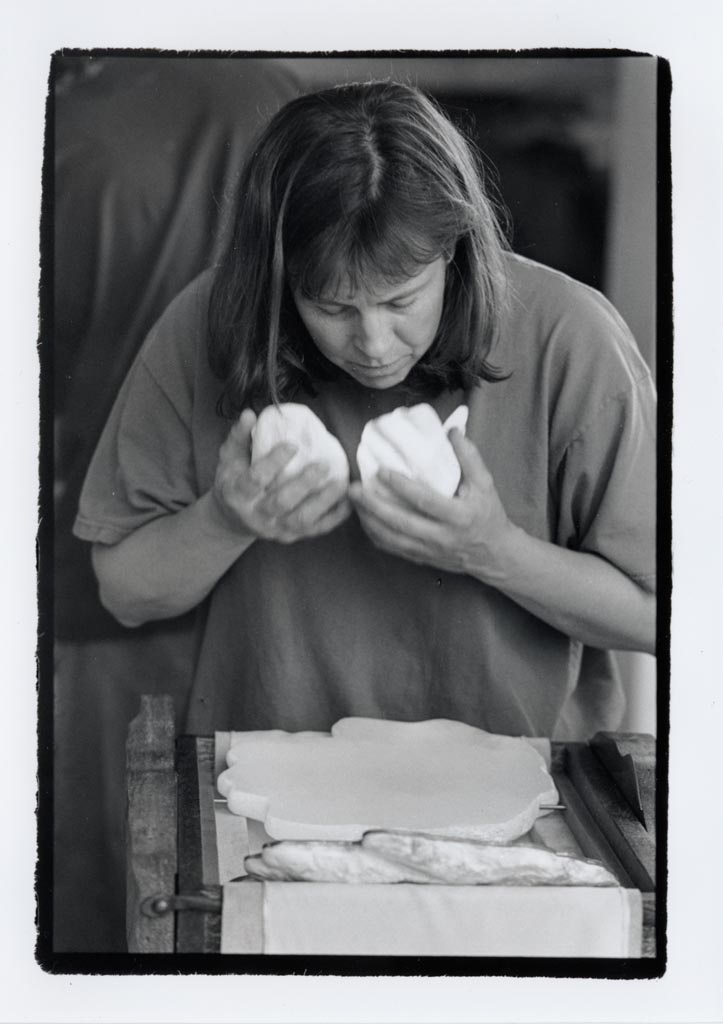

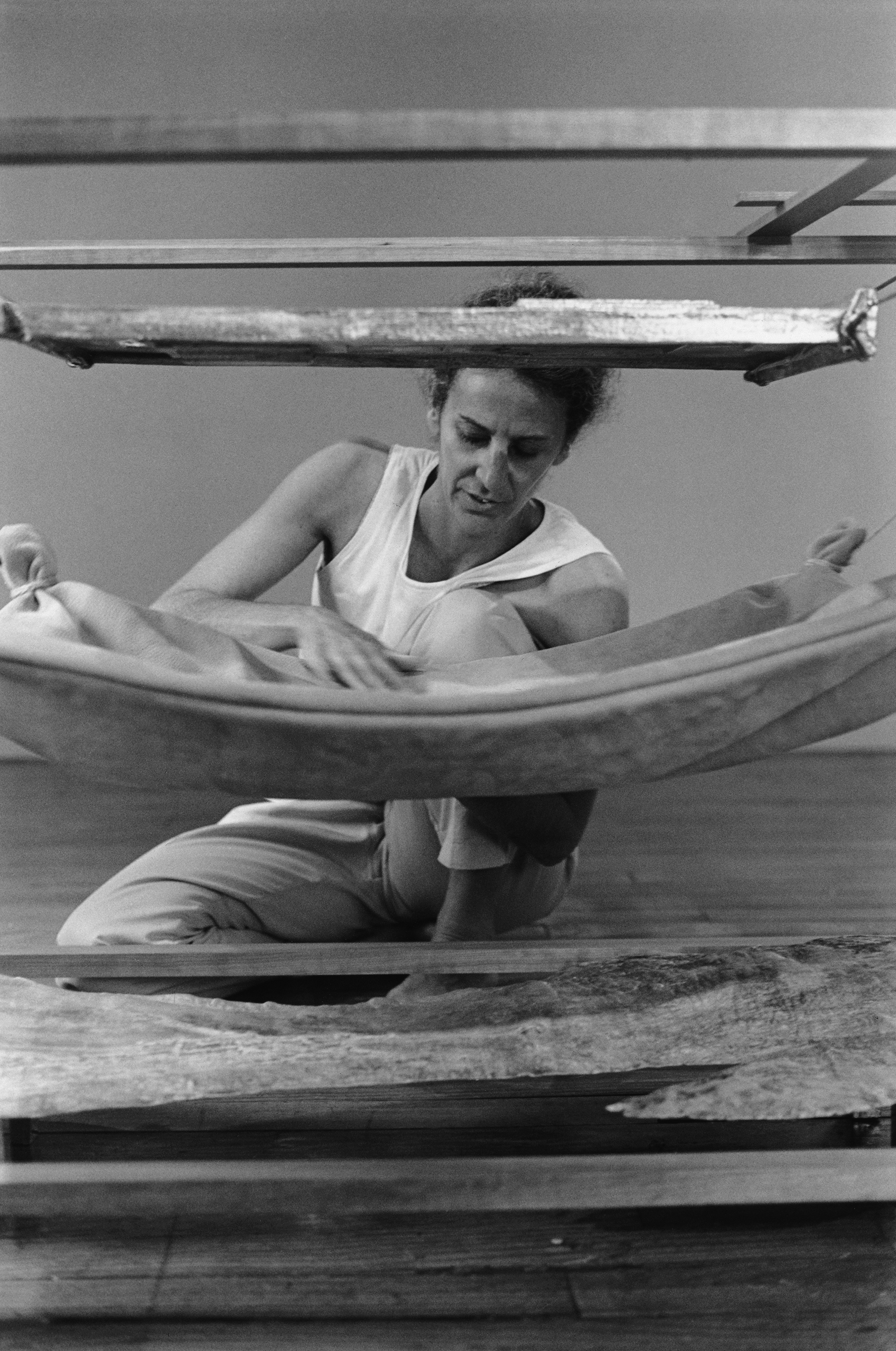

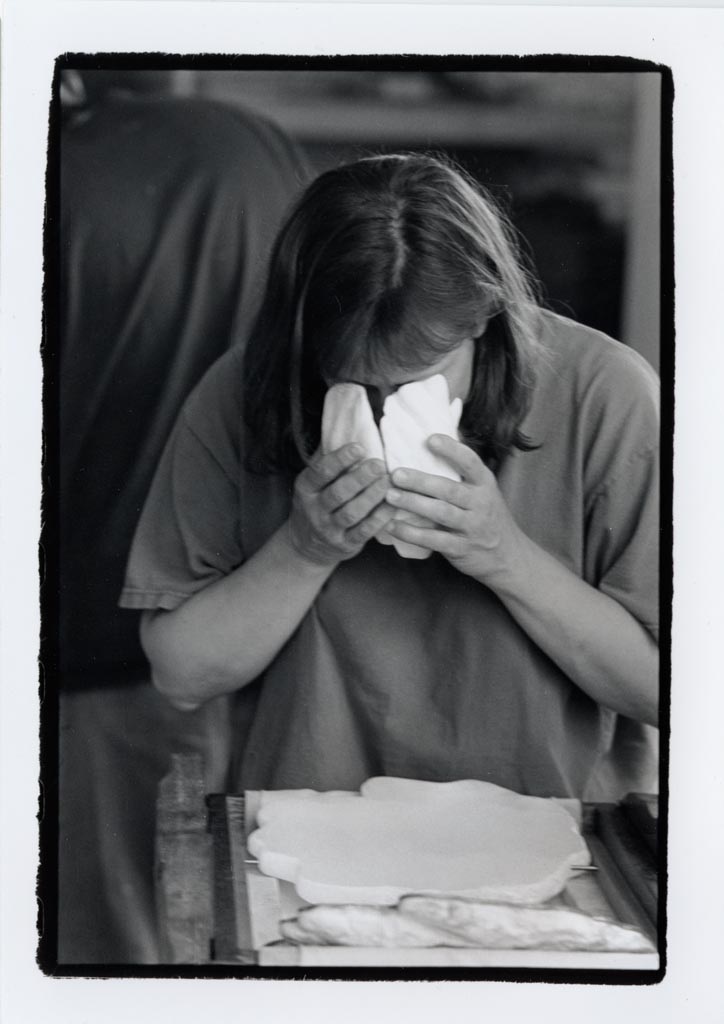

From the beginning, I made work that explored the body—not its appearance, but the feeling of being a body. Eventually I began to wonder how to make art that integrates the sensing body into all phases of the work, from conception to presentation. I became curious whether the sense of touch could be a valid way to know works of art. In response to these questions, I made sculptures designed for people to touch, initially for those who are blind. When I exhibited the tactile sculptures, I offered blindfolds to people with sight so they could experience the artworks without seeing them before they look. I discovered touching artworks in this way can be as compelling, rich and provocative as seeing them. I gathered hundreds of comments and responses from people (some of these comments are in the essay in italics). Drawing on these observations and my own explorations, I was able to build a portrait of the sense of touch. I learned to understand visual perception from a new perspective. I found a way to reimagine art, artmaking and the aesthetic experience. Out of this research I wrote a book, The Sensing Body in the Visual Arts: Making and Experiencing Sculpture, recently published by Bloomsbury. This essay is adapted from a chapter in the book.

One of the roots of our systems’ failure is their disconnection from the sensing body and its innate intelligence. The model of imagination I present here is grounded in haptic, whole-body, multisensory perception. I invite us to imagine new (and perhaps old) systems and ways of living that draw from the body’s ways of knowing.

The presence of the word image in imagination suggests that imagination is primarily visual. However, we imagine and create in every sensory mode. We can imagine a passage of music, a muscular sensation, a whiff of spice, a gut feeling. Imagination is usually defined as the faculty or action of forming new ideas, images or concepts of external objects not present to the senses. However, far from being separate from the senses, or limited to forming external objects, the imagination is integral to sensory perception itself. The very activity of perception is imaginative, creating connections between what we perceive and what we remember, between present and past. It organizes and synthesizes what we perceive, often generating new linkages and new forms in the process. Psychologist Stephen Kosslyn (1) describes the perceptual act in visual perception in this way: in order to discern what we are seeing, we compare new, incoming information or patterns to information and patterns already stored in the body-mind. For example, this unknown object I see is red, round, small and shaped like what I know of apples—it’s an apple! This process could be considered imaginative, even in ordinary perception. Linking new and old patterns potentially allows creative, imaginative connections. I might perceive the apple as something I could juggle. Furthermore, the imagination fuses input from all the senses into a meaningful unity, both in what the senses perceive and the way they are employed. By adding smell, texture and weight, the perceptions fuse and amplify the meaning of apple. And when we imagine without sensory input, our senses are still active; the brain is processing sensorially. When I imagine an apple, I might remember the crunch of biting into it, the sticky juice on my hand, the sweet fragrance, calling on visual, tactile, kinesthetic, gustatory, olfactory memories. Imagination is a way to enrich sensuous reality, both to perceive more fully and to create new possibilities. Imagination is as integral to thinking as it is a source of creativity.

Writer David Abram invites his readers to return to the sensuous engagement that indigenous people live with—to explore the imagination as a means to connect with things beyond their appearances yet remain embedded in the senses. He sees imagination as moving from the known to the unknown. He notes:

That which we call imagination is from the first an attribute of the senses themselves; imagination is not a separate mental faculty (as we so often assume) but is rather given, in order to make contact with the other sides of things that we do not sense directly, with the hidden or invisible aspects of the sensible. (2)

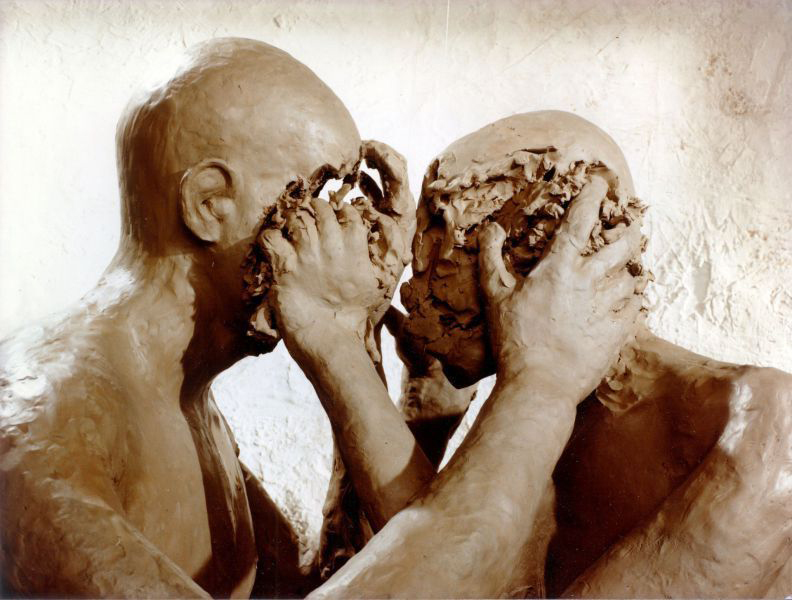

From my research, I found that touch, like the other senses, offers a way of imagining. The Czech surrealist artist and filmmaker Jan Švankmajer, in response to Communist censoring of his films, decided to turn in a radically different direction and spent seven years exploring the sense of touch. He set out to prove the existence of tactile memory and tactile imagination. He saw visual perception as being impoverished, drowning in the flood of commercial visual communications, and believed rich opportunities lay in the unsullied sense of touch:

Firstly our touch, dulled by manual work, had to be dragged away from utilitarianism and returned to imaginative childhood experiences, to the discoveries of the original world … if, in today’s world, ‘art’ has any purpose it is to liberate us … from the principle of reality … the sense of touch can play an important part, as so far it has not been discredited in ‘artistic endeavors.’

Švankmajer’s tactile experiments, tactile sculptures, and writings on touch and imagination highlight the potential of touch for aesthetic experience when freed from mundane use. He champions the erotic dimensions of touch, childhood experiences as sources of creativity, and the power of touch to reinvent and reinvigorate art perception and art making. (3)

From Jan Svankmajer’s ‘Dimensions of Dialogue: Passionate Discourse’

Imagination is not a neutral, fixed process. Beliefs about what imagination is and can do reflect the culture that spawns them. Philosopher Richard Kearney traces the history of various models of the imagination, from Hebraic, Hellenic, and medieval through transcendental, existentialist, and postmodernist. He describes the modern imagination as valorizing individual creativity, but laments that postmodernism has led to the demise and denigration of the imagination. He sees imagination today as lost in the dead end of parodic play and empty consumerist replication of images no longer grounded in sensuous reality. The current crisis of imagination is amplified by the uncertainty of truth in a climate where a plethora of media confuse facts and fiction in a fog of disinformation and distortion that leads people to distrust reality as well as, ironically, the imagination. The failure to honor the imagination’s rightful role in our lives causes the multiple dimensions of reality to flatten. Meaning disappears. Kearney suggests the next form of imagination to emerge will be more collective, relational, and inclusive of the other. (4) This is already happening in science, art, economics, psychology, and more, spurred by the dire impacts of pandemic, climate change, overpopulation, water scarcity, and species loss, forcing us to think and imagine in more ecological, relational terms. Touch, in its relational, mutual, reciprocal nature, could serve as a model, metaphor and guide for the new emergent imagination.

Whether playing with the senses or discovering hidden dimensions through them, the imagination is a way of knowing that both informs and transforms our perceptions. This is the power of art. Works of art are highly concentrated acts of perception and imagination that reveal the sheer power of the imagination to delight, disturb, and inform. Artworks provide ways to employ the imagination, both by example and by inspiration. They push the boundaries of what we know and even what we dare to explore.

I found that when touching artworks without sight the imagination is allowed to roam, released from literalism. Lacking the visual view to direct or limit, fewer boundaries circumscribe the freedom of the imagination.

I imagined a never-ending maze of steps and boxes, and when I opened my eyes, I was truly surprised. My visual senses seemed to dilute my imagination. Although the object was pleasing to the eye, I was no longer free to let my mind wander and somehow create what was in front of me.

The imagination leaps into the space-time of not knowing, ready to elaborate, associate, and even invent scenarios.

I felt isolated on a flat, cold plain that went on forever. As I slid my hands along it, they ran into things that seemed to rise up to frustrate me. The wooden inside was like heat trapped in this cold place. It made me so sad that it couldn’t go anywhere when it was turned over, closed in. This sculpture is the hardest to love, but the one that needs it the most.

Not only did this woman imagine herself as a character in a landscape with animate things, she also had a strong emotional response to the situation she had just created and projected her feelings onto the sculpture itself. The creative nature of touch is clearly evident in this response. As touch researcher David Katz observes, this creativity begins even at the perceptual level:

Every ongoing tactile activity represents a production, a creation in the true sense of the word. When we touch we move our sensory areas voluntarily, we must move them … if the tactual properties of the objects are to remain available to us…. The tactual properties of our surroundings do not chatter at us like their colors; they remain mute until we make them speak. By our muscular activities we produce such properties as roughness and smoothness, and hardness and softness. We are truly the creators of these qualities. (5)

People seem to understand this when they touch sculptures. They consider themselves as partners in the creative act.

It’s more real because I made it. It’s mine. Seeing, we each think we see the same thing, but you cannot compare your experiences of touching.

Some people are clear that their exploratory perceptual process determines the nature of the object for them. They recognize that the primary locus of the encounter is in their experience, not in the sculpture.

The dependency on seeing gave way to touch—and to inner creativity.

In a very real sense, each person creates the artwork. If several people were to describe accurately what they see or feel in an artwork, the images would be different from person to person. Everyone would notice different parts, make different connections, organize it into different configurations of form and meaning. Each person brings her personal, perceptual and cultural history to bear on the encounter. In a dynamic interplay of object and self, we make our own sense of something by selecting what interests us and then integrating it with everything we already know. This is an act of perception and imagination. Memories underlie and shine through all the senses. People see, hear and feel according to their character, past, and passions.

Artworks are projective fields. Projection is the tendency to move feelings, desires, and fears outside of oneself and assign them to other people, the environment—or works of art. The commonest kind of projection is “attributed” projection, ascribing to others feelings and characteristics within oneself, like one who hates assuming that others hate him. “Complementary” projection is thinking others feel, think, or behave the same way we do. The traits given to the other person explain one’s own. Projection is a fundamental human activity but can cause untold problems, such as when we project qualities we lack or desire onto our partners and are disappointed when they fail to live them out. Projection can be creative, as we project qualities into a story, materials, a landscape, or a work of art.

Artworks are complex and multileveled, providing ample room for projections. They call for multiple ways of perceiving and understanding. Because much is implied rather than explicit in a good work of art, we must supplement the available information by using our experience to understand it, making us co-creators with the artist. The open-endedness of art allows us to project into the artwork, alerting us to qualities or feelings we may not discern in the normal flow of experience. Art allows us to project deeply into a domain that stands apart from daily interactions. We are not bound by the normal, the expected, or the known. We are free to explore ideas, feelings, and images we do not usually entertain. We can see ourselves reflected in art in ways we have never experienced before, in ways that give us back to ourselves enlarged and nuanced.

People vividly realize they have projected an image from their experience onto a sculpture when their haptic version differs from the visual. The act of projection becomes more evident when unmasked by these differences.

Clears your mind of any binding preconceptions. Gets you in the mood for free expression. Removes pre-conceived notions of space and texture.

The mind creates what you are touching. I projected all kinds of images.

The multileveled nature of art allows us to grasp an artwork with different orders of organization and meaning, orders that can be interconnected, autonomous, or even contradictory. These orders can complement, resonate, or fuse. We can shift points of view, exchange one frame of reference for another, and replace one kind of organization with another. We can hold an artwork on several levels simultaneously, perhaps integrating them, perhaps not. We continually discover new relations and combine elements in new ways. The capacity of both artwork and perceiver to function on several levels at once and over time helps explain why haptic experience of an artwork can be different from or contradictory to the visual experience and yet contribute to a sense of the whole.

A visual work of art is a condensation or translation of experiences in other sensory modes as well as visual. The whole sensory continuum informs the conception, making, and perception of a visual artwork. While looking at a work of art, we use sensory memories from the nonvisual senses. The ability to draw on haptic experience is especially critical to visual appreciation of art since sight and movement are so thoroughly entwined in our sensory systems. When sight and touch are used together, under ordinary circumstances sight dominates and touch supports. The objectivity and dominance of sight have convinced us there is a singular reality. However, when people separate the two senses by touching without seeing, they generate two distinctly different images of a sculpture, first by touching and then by looking. This disjuncture of impressions created by the two senses undermines the usual picture of reality, fragmenting its monolithic nature. Seeing never has the same authority after we realize that touching produces a different, equally interesting and valid sense of the object. Which is the “real” version? Both may be real and compelling, suggesting that reality is multiple and mutable and that it is, to a larger extent than we may have realized, a function of our mode of perception and of our personal consciousness. People grasp in a concrete way the inventive, imaginative nature of perception. They realize that reality is a function of imagination.

The imagination also generates the capacity for identification with an artwork. We can imaginatively identify with a figure, with an element, or with qualities perceived in an artwork. For example, we might feel ourselves tall and thin when touching a tall, thin sculpture, or spacious inside while exploring an interior space, or balanced when encountering a symmetrical pattern.

This sculpture makes me feel more organized, more coherent.

Our sensory history underlies our experience of an artwork. A vast part of this sensory history is tactile, haptic, and kinesthetic. The somatic senses fuse our inner experience with what lies outside ourselves. They confirm and maintain a sense of ourselves. The capacity of touch to connect inner and outer conditions, mind and body, self and world, underlies our ability to make imaginative connections. Touch is the sensory system that, by its very nature, infuses—and fuses—multiple dimensions of our experience.

The sense of touch is dynamic and subjective. To the eye, sculptures appear to be solid, static, and composed, but the person touching them supplies movement, vulnerability, and subjectivity. The words Rainer Maria Rilke used to describe Japanese poetry could also apply to the haptic experience:

Le visible est pris d’une main sure, il est cueilli comme un fruit mur, mais il ne pese point, car a peine pose, il se voit force de signifier l’invisible.” (The visible is taken by a sure hand, picked like a ripe fruit, but it weighs nothing because, as soon as taken, it is forced to signify the invisible.) (6)

When we touch something, our sensations, impulses, intentions, associations, memories, and imagination fuse into our experience of the object, complicating and enriching it, drawing multiple dimensions of ourselves into one gesture. Touch is the most physical and corporeal of the senses, but is also a gateway to the intangible and the invisible.

You touch and it opens a new world, then you touch something else and there’s yet another world.

Colour photo by David Stansbury, black & white photos by Ellen Augarten

Rosalyn Driscoll’s work has explored the somatic senses and the language of the body for decades. She has made tactile sculpture, designed haptic exhibitions for people with visual impairments, and researched tactile perception through artwork, evaluations, and conferences world-wide with scientists, engineers, psychologists and philosophers. Her writing on art and touch has been published in collections on art and perception from Oxford University, MIT and Ashgate. You can find out more about her work on her website: www.rosalyndriscoll.com

Rosalyn’s book The Sensing Body in the Visual Arts is out now:

https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/the-sensing-body-in-the-visual-arts-9781350122222/

Notes

- Stephen Kosslyn, Image and Brain: The Resolution of the Imagery Debate (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1994)

- David Abram, The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-Than- Human World (New York: Vintage Books, 1996), 58

- Jan Švankmajer, Touching and Imagining: An Introduction to Tactile Art (London: I.B.Taurus, 2014)

- Richard Kearney, The Wake of Imagination: Toward a Postmodern Culture (New York: Routledge, 1988)

- Katz, David, ed. and trans. Lester E. Krueger, The World of Touch (Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum Associates, 1989)

- Winkelvoss, Karine, Rilke, la pensee des yeux (Paris: University de la Sorbonne Nouvelle, 2004) 211