TT Journal, Vol.1, ISSUE 2, 19th March 2021

This is an overcast Saturday morning in Johannesburg, the 12th March 2021, these are answers for Tereza Stehlikova and the Tangible Territory.

When thinking of you and your artistic practice, I am always extremely drawn to your trust in the creative process, the openness and responsiveness to materials, environments, situations and of course other people with whom you collaborate. All of this happens very much in the domain of a physical, material, embodied reality. When the pandemic came and with it all the constraints, all of this has come to a sudden halt. Instead, it has been replaced by mainly audio-visual interactions. What are your thoughts on this virtualisation of our human encounters in terms of collaboratively making and also experiencing art? Is there a way of challenging this tendency? Should it even be challenged or do we need to accept this as part of a natural evolution?

I think, I mean my hope is that these zoom and virtual world we have been pushed into during lockdown will be analogous a bit to the microwave in the kitchen. There was an idea at some point when they first came out that microwaves were going to be the end of stoves and ovens and the traditional kitchen, that everything could be done in this new radiantly technique. And now we understand that in fact it’s useful for reheating food, warming the milk, warming a baby’s bottle, heating a plate. Certainly, it has a role but is has not had anything like the effect that people expected.

There are some things that will certainly change and stay there: I am sure video conferencing will stay for a lot of business and a lot of administrative meetings. But in the arts there is something about the embodiment, the movement of the body, the feeling of muscles, the contact with other human beings, the seeing, the listening the touching, whether you are making or whether you are watching, which is very different and which I think there is a hunger for after such a long period of isolation.

I think in terms of watching cinema it’s very likely that will largely stay at home. And here I am speaking for myself, of the ease of watching something on one’s bed as opposed to going to the cinema. But I think the question of a live theatrical performance, live musical performance is very very different. In a concert performance or in a theatre performance I generally feel much more aware of being in an audience, watching something being done for me than I would in a cinema. Even if it is a full cinema it feels a much more solitary experience of watching.

I don’t think we need to accept the virtualisation of the world as a natural evolution. I think that it will become a part, and a bigger part than it has been before, but this future prediction which I am very sceptical of, for my own part. I always get it wrong, whatever I predicted about the future has always been completely unreliable.

Can you tell us what impact the physical distancing has had on your own creative practice and in what ways did you adapt or refused to adapt, or even embraced or simply accepted the situation? Do you think that your own creative process been affected to an extent that it is apparent in the resulting work itself?

In South Africa we are still very far away from getting mass vaccinations. And so we are going to have another, I would guess a year, of either more or less of physical distancing depending on waxing and waning of the pandemic here. But last year we started with one of the most rigorous lockdowns and when that was lifted after 8 weeks, it was possible for performances and filmmaking to start again. And we did that in the studio and The Centre for the Less Good Idea and immediately about 13 or 16 of us got Covid. Luckily, we all survived and then we had the strange circumstances of being like a post-Covid studio. Almost all the people in the studio have had Covid and so couldn’t either get it again or give it to someone else, certainly during those first many months of immunity. And so we were able to work in a much more relaxed way than many other people could. And so throughout the middle of last year, although travelling was impossible, there was this blessed period of many many months of uninterrupted working in the studio, something I haven’t had for 45 years.

So while in some sense this was an extremely productive and good period of work for me, I was also so aware that so many of the collaborators I work with, musicians, actors, technical people, were not only not able to earn an income but not even able to practice their metiér. They couldn’t get to their studios if no performances could be done.

Additionally, do you have a sense of how the sharing of your art might be transformed, in the long term and does this have any impact on how you think about making work?

I think there are new forms which have emerged. Whereas general Zoom webinars and Zoom panel discussions are a nightmare for me and I of course had to take part in more of them than I would like. But it seems a very terrible form. To be talking to people when you can’t see them, you can’t see whose bored by what, who is interested, all the micro signs we get of knowing that we live in a community of human beings disappearing. People have both their microphones and their cameras switched off. And even if they don’t, to look at an audience of 200 in front of you or to look at 200 postage stamps on a screen is a very different experience.

The one exception I would say has been talks which have been in the form of me in my studio informally talking to people and showing them the studio. This is something that’s not possible in an in-person lecture when you are not in your studio and you don’t have your studio to walk around. And there has been an intimacy and informality in a lot of those interactions which is something gained, which one had not had before, haven’t thought of doing before and which I am sure will continue. But for a more considered formal lecture Zoom has been a very unsatisfactory form to make a lecture, slightly less unsatisfactory to listen to other lectures. But even then I would much rather watch a recording of a lecture done in front of a real audience.

I am occasionally seized by a sense of fear that these current restrictions will permanently affect the way we human beings interact, what we expect and even what we want from the arts. As an example, may we just get accustomed to watching films from our living rooms, rather than crave theatre and live performance in the presence of others? Do you have any evolving thoughts on this?

We had our first live performance at The Centre for the Less Good Idea couple of weeks ago. A small audience in a largish space so that there was lots of distance and lots of air between everyone. A musical performance of 6 musicians and about 70 people in the audience and it was astonishing the delight that the people had in being back together and seeing something live in front of them. The pleasure was palpable. But it took an effort. I think I found it in myself also. A kind of hermit like retreating. The default position after supper is to either go back to my studio, or to watch something on a screen. And the thought of getting up: Getting into the car, driving all the way through town, looking over your shoulder as you park your car in dodgy parts of town to go to the performance is an effort. So there was a hump to get over but when that was over there was an enormous satisfaction in being back in. There was a feeling of: “Oh yes I remember, we used to do this.” And whether enough people will remember or get over that hump is yet to be seen.

In your recent video discussing the pandemic and post pandemic theatre (July 2020), you also expressed your disagreement with the idea of a “lockdown time” as being a reflective pause. You said that interesting ideas usually emerge from the energy of collaborations with others. Can you say more about this and is there anything that this “vacuum” offers that can be beneficial creatively?

I think that temperamentally people work in different ways. There are some artists who don’t want anyone to see their work until it is finished, who want to make sure everything is perfect. I am the opposite. I kind of need as it emerges to be seeing the work in other people’s eyes, to see how it is being received, to see which sections seem to be intriguing or not. It’s a kind of trying to see myself in other people’s looking at the work.

And so even when we arrived in lockdown, one of my assistants and collaborators, who lives on our property was part of our bubble and he worked with me along a film project we were working on. And some of it I could have done entirely on my own but it would have been very difficult not to have the conversation, the looking through somebody else’s eyes.

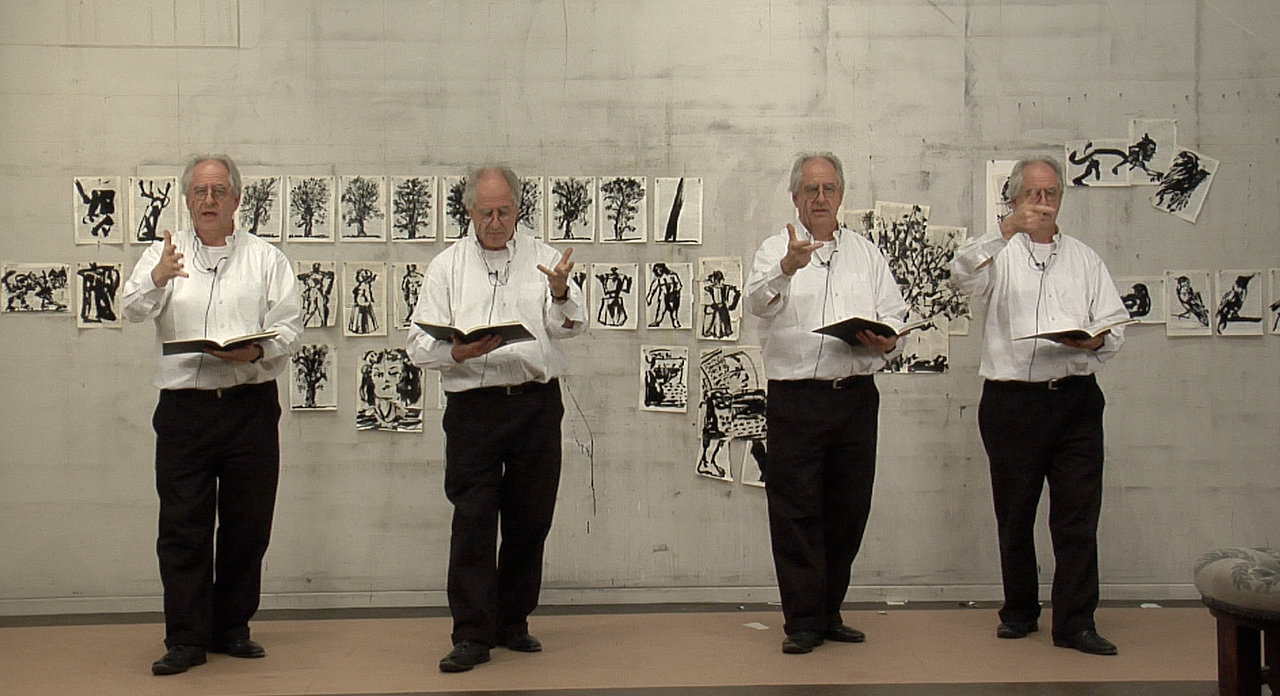

I presume for many writers for whom there is no conversation until the words are on the paper the vacuum time was good and was productive. For me it made it possible to work on the long-term project which is a series of films about the studio. About what happens in the studio. The studio as a place of making and of making sense. Which I‘d wanted to do for a year or more. It was finally possible to have the open months to work on it a bit. It will be a series of 8 or 9 episodes, each about 40 min long. And it’s a two-year project. So to have uninterrupted time to work on it and since the extreme lockdown being able to work with a small crew in the studio and sometimes even with performers, has been a blessing. And the project is now just about half way done, another 4 episodes to make. I hope to be able to finish it this year or early next year. Which would be impossible with the usual normal schedule of exhibitions in other parts of the world and particularly rehearsals and performances in different places.

When teaching my students online, or interacting with colleagues, I often have a feeling of speaking through a blanket: we can see outlines of each other and can speak and hear, but the communication is mediated by the screen, all subtlety of nonverbal expressions is lost…not to mention our proximity senses which are being left behind. Basically, it feels like a crude form of communication. The experience also disappears from memory much more quickly. What is your view on the video call technology, such as Zoom and do you see any potential in what it has to offer? Any way it can be used more creatively?

I mean the technology is astonishing and the quality of image, if you think what the image at the start of Skype was when the first internet video conferencing technology had started, it does grow and change and the resolution gets better and people learn how to use it. It’s a bit like the change from I suppose when you had studio photographers taking photographs and then the advent of the Brown Box Brownie camera. It went from an era of very beautiful images and carefully thought images of how people look to that kind of disappearing. And we are in that phase now. If you think of the ugliness and crassness of the zoom images, images of zoom, what people are showing you and how people appear and what their presence is compared to their presence in life or on a stage. But presumably there will be a way that this will change and can be improved.

Do you have any thoughts on the role art can play in making sense of our situation or even subverting this tendency towards virtualisation?

Art always is about making sense of situations, complex or simple, of showing contradiction and paradoxes of uncertainty. But I think uncertainty has been one of the key words of this pandemic: Not even the most informed scientist or people really having an idea of what was going to be the next step, of what was best practice, or what policy should be followed. So something that artists have been castigated for, for being so vague, so uncertain, for putting one line down and changing it and putting another line. In some way this is a good demonstration of how the world is.

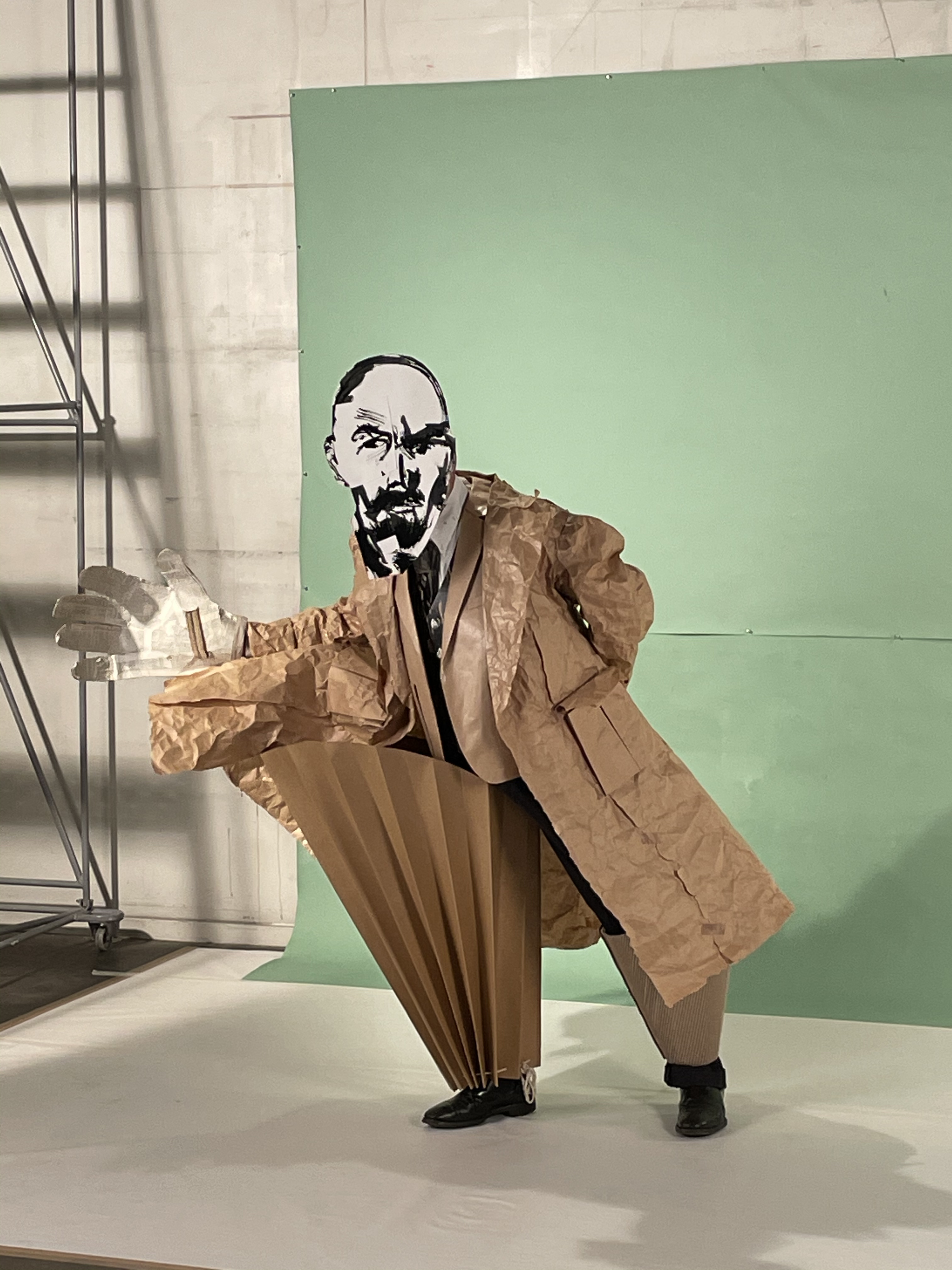

I find myself both resisting and embracing [virtualisation]. So I work on a project now, which is, apart from this long film term project about what happens in the studio, a project which is a film for a Swiss orchestra playing a Shostakovich symphony. So the orchestra will be playing live, with a live audience in a real concert hall and on the screen behind them the film will be projected that I am making. And it is a film (because it is a Shostakovich symphony) from the 1950s, I am busy working with my designer, making models of a kind of possible Soviet museum in which this film will unfold.

Can you tell us what you are you working on right now?

There are 3 things that I work on. One is this literal film that I work on for the Swiss orchestra, the second is thinking what would it be to digitise these model sets that we are making, very beautiful sets we made of cardboard, photostats things like that and the paper and wooden puppets that we are putting inside it. Scan them, do digital mapping of them, 3D creation, put it inside a game engine and have people as it were navigate inside this strange space we are making, examine the different rooms. Put a live performance in there. And that’s turning the cardboard into a digital virtual reality. But at the same time as I am seeing it, I am thinking this would be a rather fantastic theatre performance, made full scale, these models enlarged to a larger scale or put in different rooms of a museum, which you walk through seeing different live performances happening. So it both has a real incarnation, which is the film, which is under way and a possible digital existence, and a possible live performance existence. And all of these things swirl around and the film will be real and the live performance – maybe and the digital – maybe. So it’s both embracing and resisting the algorithm.

And the piece finally I guess has to be about the edges of the human. There was the Soviet attempt in the 1920s by so many writers, Trotsky amongst others, to think of the human as a machine that could be perfected by a good human engineering, the way a machine would be. There is a tendency now, not a tendency but a project to see how human machines can be, both in terms of learning and performance and all of those things. So these edges of the virtual and the real, or the mechanical and the real, are questions which have been there for quite a while and which continue in different forms and so the project, one way or another, will both embody but discuss, or be concerned with those questions.

Listen to William Kentridge’s answers in an audio:

William Kentridge (born 28 April 1955) is a South African artist best known for his prints, drawings, and animated films. These are constructed by filming a drawing, making erasures and changes, and filming it again. He continues this process meticulously, giving each change to the drawing a quarter of a second to two seconds’ screen time. A single drawing will be altered and filmed this way until the end of a scene. These palimpsest-like drawings are later displayed along with the films as finished pieces of art. Kentridge has created art work as part of design of theatrical productions, both plays and operas. He has served as art director and overall director of numerous productions, collaborating with other artists, puppeteers and others in creating productions that combine drawings and multi-media combinations. https://www.mariangoodman.com/artists/49-william-kentridge/

Many thanks to William Kentridge and to Anne McIlleron for making this happen and also for the images provided.