TT JOURNAL, VOL.1, ISSUE 3, 8TH OCTOBER 2021

Lucas Battich

In the spring of 1887, seven-year-old Helen Keller was holding her hand under the running water from a well spout. Keller had lost her sight and hearing at nineteen months old, growing into a withdrawn child and struggling to make herself understood. She lived, as she later put it, “at sea in a dense fog” — until that day in 1887, when her teacher Anne Mansfield Sullivan, herself visually impaired, taught her her first word:

As the cool stream gushed over one hand [Miss Sullivan] spelled into the other the word water, first slowly, then rapidly. I stood still, my whole attention fixed upon the motions of her fingers. Suddenly I felt a misty consciousness as of something forgotten—a thrill of returning thought; and somehow the mystery of language was revealed to me. I knew then that “w-a-t-e-r” meant the wonderful cool something that was flowing over my hand. (Keller, 1903: 23)

Using their sense of touch, Sullivan made the water present to Keller through their shared attention to it, and could then name it through her movements. In what Keller later called her “soul’s sudden awakening”, this episode became her entry into the social world of communication and language.

From caregiver and infant coordinating together their attention on a toy while learning its name, to singing duets or playing in a jazz band, humans jointly attend to what they see or to the music they make together. We can share our attention to the beauty and aroma of wild spring flowers, doctors jointly assess radiographs to detect tumours, and hunters can jointly attend to the sound of birds in the trees.

Between the age of nine and eighteen months, most of us develop the ability to reciprocally coordinate our attention with others on a third object of interest, otherwise known as joint attention. Engagement in joint attention contributes to vocabulary acquisition and language learning. It provides a context for the child to associate words and signs with their referent. Joint attention even plays a crucial role in the development of our ability to infer and understand other people’s mental states, as well as more sophisticated forms of social cognition and action coordination.

We constantly coordinate attention in multisensory rich environments. The canonical example in research, however, remains one where joint attention mostly relies on gaze coordination and visible pointing gestures, and focuses on visible targets. Since the term was introduced in developmental research by Jerome Bruner and colleagues in the 1970s, joint attention has been studied by using eye-gaze and pointing behaviours. As one influential paper puts it: “Operationally, a key feature of joint attentional behaviour is that at some point the infant alternates gaze between person and object, for example, looking back to the adult for a reaction as she points to a salient event” (Carpenter, Nagell, Tomasello, Butterworth, & Moore, 1998). But aren’t non-visual senses useful, or even necessary for us to coordinate our attention in some distinctive ways?

In our recent work (Battich, Fairhurst, & Deroy, 2020), we argue that this narrow focus misses how joint attention operates, and what it achieves: joint attention draws on multiples senses to resolve the ambiguity of our referential intentions, and to coordinate both on non-visible and more abstract aspects of the world. Moreover, an overemphasis on eye-gaze coordination can also misrepresent the intersubjective capacities of persons with sensory deficits (e.g., deaf, blind, and deaf-blind). In a particularly egregious example, a psychologist publishing in 1977 suggested that blind children should be trained in eye contact and correct facial orientation, just because this makes it easier for sighted interlocutors to interact with them. Helen Keller’s experience of language learning shows the importance of providing a principled way to explain the role of non-visual modalities in joint attention.

We propose that non-visual modalities have not only a supportive role alongside vision, but become necessary to establish the difference between attending to a sensible aspect of a multisensory object and to the object as a whole, and to account for how agents coordinate their attention on non-visible targets.

When non-visual senses facilitate visual joint attention:

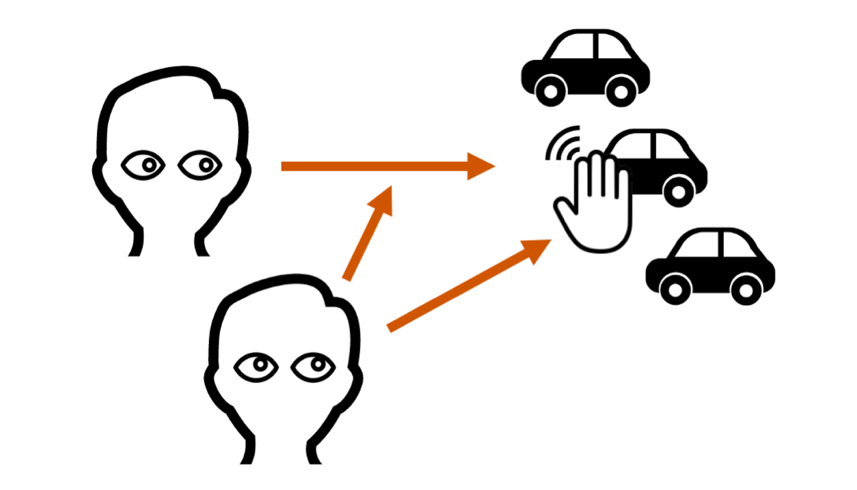

Using only vision could of course be sufficient to coordinate attention, but in many social contexts it may not always be the most efficient way. In information theory, adding redundancy to the initial message so that several portions of the message carry the same information increases the chance that the message will be accurately received at the end of a noisy channel. This is also true in perception. Imagine trying to hit a nail with a hammer. It is possible to position the nail in the wall and then hammer it while relying only on vision. But by holding the nail with one hand, you can gather information about the nail’s spatial position both through vision and through touch. This is the whole premise of the German party game Hammerschlagen, where you have to hit a nail into a stump. The game is hard precisely because you are not allowed to grip the nail with your free hand. Studies in multisensory perception demonstrate that redundant information gathered across several sensory modalities increases the reliability of a sensory estimate: it increases a perceiver’s accuracy and response time to detect the presence of a stimulus and to discriminate and identify a sensory feature, such as an object’s shape or its spatial location. It is safe to assume that redundancy of information across modalities is also usefully exploited when establishing and sustaining joint attention. For example, I wave a toy car in front of your line of vision, while pressing a button that causes the car to make a noise. The combination of visual and auditory information will facilitate your accuracy and speed for coordinating attention to the toy car (figure 1).

When processing information about the other’s attentional state, we can also distinguish between the sense I rely on to monitor the other’s attention (I look at your hand grasping), and the sense they use, which I monitor to gather information about their attention (I look at your hand grasping). When we see someone touching something, similar neural circuits are activated that are normally involved when we execute those actions. In this way, we can vicariously gather tactile expectations about a jointly attended object just by using sight. Observing someone’s hands can often be more informative than observing their eye-gaze, and may in fact come first during development. For example, Yu and colleagues (Yu & Smith, 2013) had infants and parents play with a set of toys in a free-flowing way, while their eye and hand movements were measured. They found that one-year-old infants do not tend to follow a partner’s gaze to monitor their attention. Instead, they follow their hands. This evidence suggests that non-visual senses and multisensory expectations are exploited in joint attention, especially to narrow down the spatial location of the target of joint attention by combing redundant information from different senses. This study is one among several recent studies using interactive and ecological settings that suggest that joint attention between infants and parents is a multisensory activity, just as many other ways of communication. Reliance on multiple senses and their interaction can here help provide richer spatial and temporal representations of our environment.

When multiple senses are necessary for joint attention:

The dominance of vision in the study and theorising about perception and joint activities may indeed reflect the importance of this modality in humans. Gaze behaviour can be easily measured and controlled in laboratory conditions and is, therefore, a powerful means to study joint attention. But the dominance of vision in our lives and in research should by no means occult the fact that humans also jointly attend, or teach words referring to, sounds and smells of animals, musical features, or texture of materials. The focus on vision might incidentally misrepresent certain teaching and communicative cultures, where touch, sounds or smells might come to play a more important role (Akhtar & Gernsbacher, 2008).

One clear limitation of audition or olfaction is that the target of attention is not so publicly disclosed to others as a visual target would. If we want to coordinate our attention on strictly non-visual targets, we may be obliged to indirectly coordinate on the visual location of these non-visual events and use cognitive strategies to infer that the target is non-visual. For example, pointing at the relevant sensory organ, as when touching one’s ear, or one’s nose, can provide evidence to others of my intention of attending to a non-visual stimulus. This all seems very obvious to us adults, but the developmental trajectory of sharing sounds and smells is not yet fully understood. Although visual and gestural ostensive signals are often used on some occasions to direct attention to a non-visible target, such behaviours already presuppose that the other person is capable of understanding that sounds and smells are objects in the world that can be perceived together with others. The developmental trajectory of the ability to gaze at objects jointly with others is well researched. One outstanding question is when infants start to display an equivalent understanding that others can share with them attention to smells and sounds, and how this understanding is coupled with processing the visual attention of others.

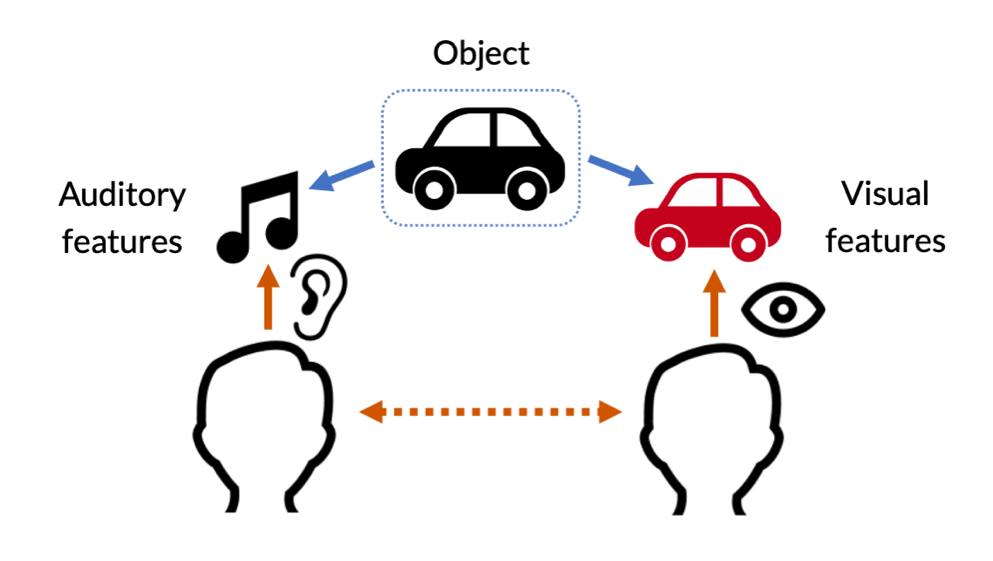

Things get more complicated when coordination occurs on objects that two people will experience through different modalities. This is the case, for instance, when coordinating attention with blind individuals, or individuals whose vision is temporarily blocked (say, they wear opaque glasses). Here, both or at least one agent knows that the other cannot access the object on which attention needs to be coordinated via the visual modality that they themselves use to access the object. Tactile joint attention is crucial for children with visual impairments and multiple sensory disabilities. For example, a child rolling Play-Doh leads the adult’s hand to share attention to her activity. The adult can follow the child’s lead and focus on what the child is doing by keeping noncontrolling tactile contact both with the child’s hands and with the Play-Doh, establishing a reciprocal relation. Núñez (2014) reports that deafblind children tend to combine two or more sensory sources for coordinating attention toward an object with their non-deafblind parents. A 3-year-old child with profound visual and hearing impairment would first tactually check for her caretaker’s attention, then hold the object of interest towards the caretaker’s face with one hand while continuing to monitor their attention with the other hand, vocalizing excitedly and smiling throughout. Adopting a multisensory perspective on joint attention can provide better measures of the development of atypical children and inspire new complementary strategies to foster the development of joint attention skills.

Figure 2. When coordinating on objects we each experience through different modalities, we must monitor each other’s sensory access relative to the target to successfully achieve coordination.

A better understanding of the interplay of different sense modalities during joint attention also has direct implications for other sectors and fields. Take social robotics, which currently strives to bring artificial agents into hospitals, schools, businesses, and homes — complex social environments that require the enactment of naturalistic interactions, including coordinating attention to the same things. For a robot to help a human partner assemble a piece of furniture, stack blocks with children in the playground, and assist people with disabilities in their daily lives, they need to be sensitive to what the human is attending to, and asking them to attend to. But whether an artificial agent can successfully engage in joint attention with humans will depend on how well they can meet human expectations. Will they be able to both initiate and follow attentional cues in a naturalistic manner? Current research efforts are focused on trying to give eyes to artificial social agents, including autonomous robots and virtual agents, in a way that mimics human gaze behaviours. However, human-robot interactions will not be seamless if we leave behind the different ways in which non-visual sensory modalities are used by humans to coordinate with each other. By adopting a multisensory perspective on human-robot joint attention, it is possible to examine non-visual cues emitted by the artificial agent, so that they accord with the expectations of human interaction partners. Being sensitive to the non-visual cues emitted by humans could also improve the spatial and temporal resolution of attention-orienting in robots.

Taking seriously the role of non-visual senses during joint attention can also shed light on the strangeness of virtual meetings. During a shared Zoom presentation, we can of course coordinate our attention to the same figure or text being shared across everyone’s screens in the meeting. But even when using language, this coordination is by no means straightforward, because of a simple barrier: it is very difficult to tell where someone’s attention is focused. This is not just because we cannot see their computer screens (maybe they have other windows open and are browsing the internet while in the Zoom call), but even if you could, the problem is even more basic than that. You cannot tell precisely where their gaze is directed, and it is very hard to read and interpret their bodily movements. All the beneficial effects of combing redundant multisensory information to determine someone’s attentional focus are gone during virtual meetings.

Building a shared reality:

The difficulties of coordinating attention in a virtual world may point to the importance of this ability to create a shared objective reality between us. Several philosophers and psychologists argue that joint attention is, in fact, essential for the development of a shared objective world, where objects are attended in common. Being able to coordinate my attention to an object together with another individual, goes hand in hand with the ability to experience the object as a mind-independent thing separate from myself. Philosopher Donald Davidson argued that we come to know reality through a process of triangulation, when our mental states and those of others are directed towards the same target. Only then, and through other people, are we able to secure knowledge of the objective world outside us (Davidson, 1999). This view has pre-eminent precursors in psychology. Lev Vygotsky, in particular, held the doctrine that all higher cognition in an individual arises from an internationalization process of prior social interactions. Children acquire many of their cognitive abilities, beliefs, and decision-making strategies, through continuous social interactions, including the basic accomplishment of joint attention (Vygotsky, 2012).

Granting that joint attention helps us build a shared objective world, restricting ourselves to gaze and vision alone would make this world incredibly impoverished. This restriction is more salient when we focus on the question of how people understand each other’s pointing gestures. In his Philosophical Investigations, Ludwig Wittgenstein challenged his readers to point first at a piece of paper, then at its shape, now at its colour, and at its number (which certainly sounds odd). He noted that, although the pointer will have “meant” something different each time they pointed, it cannot be clear from the behavioural aspects of each pointing gesture what is being pointed at — whether the shape, the colour, the fact that it is one piece and not two or three, or just the whole piece of paper. Pointing gestures, as well as other ostensive signals, are said to be, by themselves, highly ambiguous. Since Wittgenstein, scientists and philosophers alike have attempted to determine the set of contextual conditions that an ostensive signal such as pointing must satisfy, so that its intended reference is unambiguously fixed. This is particularly pressing when the shared knowledge between interacting individuals is limited, as can be the case with very young infants and non-human animals. By and large, this endeavour has centred on visual gestures and on language. Moreover, the ambiguity of ostensive gestures has been usually diagnosed on the basis of isolated and idealised unisensory (usually visual) gestures, such as pointing, and stripped of the emotive and bodily complexities in which such gestures are embedded in reality. The starting point, in other words, is an impoverished version of interactions involving ostensive references, including joint attention. Taking into account the role of multisensory cues and the social strategies they support, can help to dispel this impoverished view.

To stress this point, imagine a case where joint attention would only occur through following others’ eye-gaze and looking at pointing gestures: we would only be able to coordinate attention on the visual properties of objects and events. We would certainly be able to learn that most bananas are yellow; we would learn that using colour-tinged glasses changes how these properties look like; and we would learn that other people may be seeing a drawing upside down when we see it right side up. But how would two people jointly attend to the sound of thunder — or the smell of flowers?

A multisensory approach to joint attention introduces further empirical and theoretical directions, which can be investigated only by bringing together methods from social cognition, attention research, and multisensory research. Although vision-centred research continues to provide valuable insights into the workings of joint attention, taking into account the several roles of non-visual senses will advance our knowledge on how people establish, maintain and tune joint attention to a range of sensory objects and features.

References

Akhtar, N., & Gernsbacher, M. A. (2008). On privileging the role of gaze in infant social cognition. Child Development Perspectives, 2(2), 59–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-8606.2008.00044.x

Battich, L., Fairhurst, M., & Deroy, O. (2020). Coordinating attention requires coordinated senses. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 27(6), 1126–1138. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-020-01766-z

Carpenter, M., Nagell, K., Tomasello, M., Butterworth, G., & Moore, C. (1998). Social cognition, joint attention, and communicative competence from 9 to 15 months of age. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 63(4), i–174. https://doi.org/10.2307/1166214

Davidson, D. (1999). The emergence of thought. Erkenntnis, 51(1), 511–521.

Keller, H. (1903). The Story of My Life. New York, NY: Doubleday.

Yu, C., & Smith, L. B. (2013). Joint attention without gaze following: Human infants and their parents coordinate visual attention to objects through eye-hand coordination. PLoS ONE, 8(11), e79659. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0079659

Lucas Battich is a postdoctoral philosopher and cognitive scientist at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich. He obtained a doctorate from the Graduate School of Systemic Neurosciences in Munich, on how different senses shape joint attention and, conversely, how joint attention can affect perception across modalities. His research is focused on social cognition and perception, combining tools from philosophy of mind, experimental psychology and psychophysics. Before coming to Munich, he studied philosophy, fine arts, and cognitive science at the University of Dundee, the Piet Zwart Institute in Rotterdam, and Radboud University Nijmegen. https://lucasbattich.com/