TT Journal, ISSUE 5, 20th January 2023

By Becka McFadden

Audio version:

Prelude

What happens when we lose access?

What if we can’t go inside?

What if there’s nowhere to come to rest?

What is this life on the edges, the peripheries, of buildings?

What interiors do I need? What interiors do I miss?

What interiors do you miss?

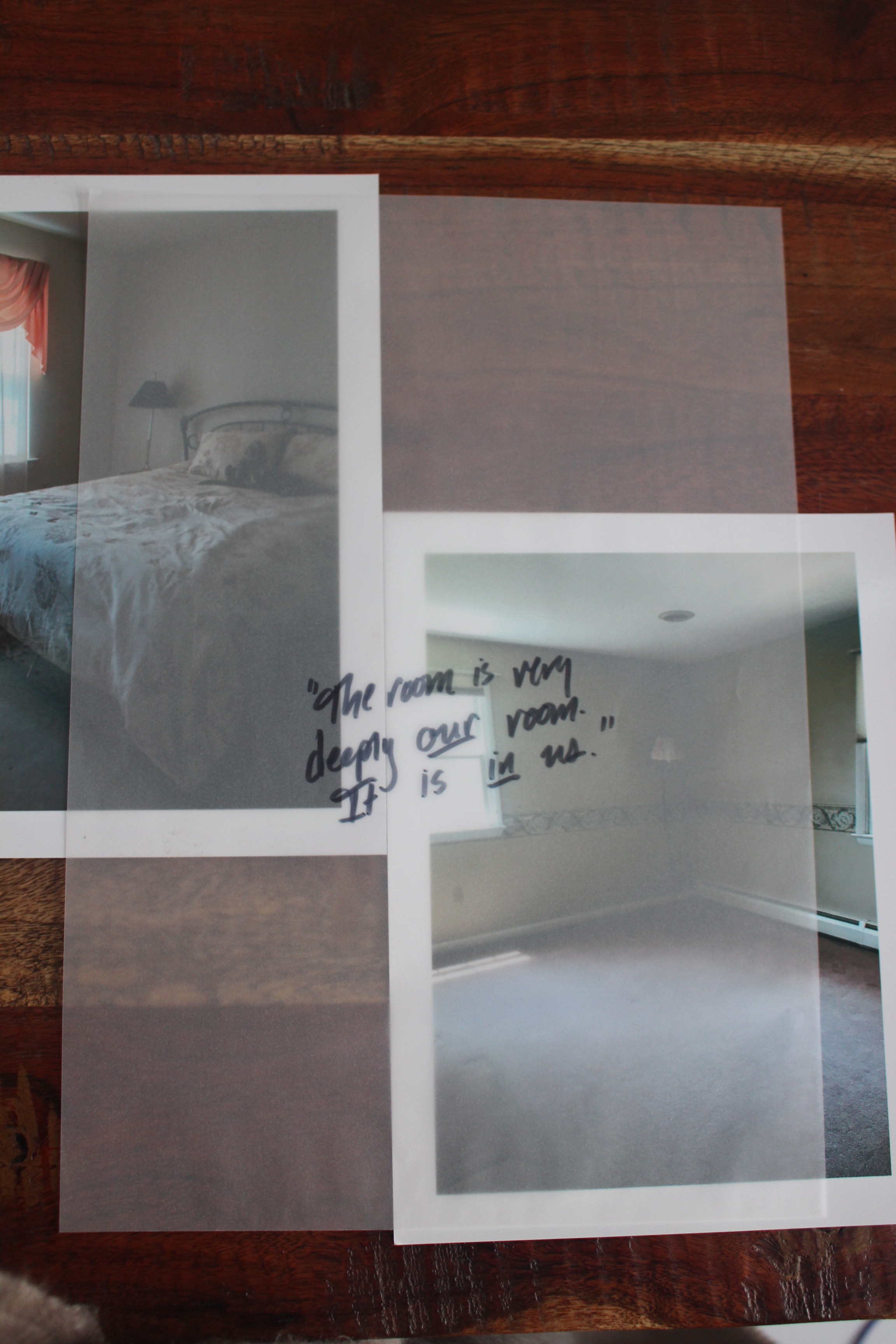

Movement I.

“The room is very deeply our room, it is in us. We no longer see it. It no longer limits us. And all our former rooms come and fit into this one.” – Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space

There was a big, beautiful tree here.

This porch should not have screens.

I wonder if the basements still smell of canned vegetables and damp and the 1950s.

Is it possible to tell, anymore, that there was once a fire in the living room? My mother let me see it right after it happened. She told me later that was a mistake, that I was too young, but she was in shock and wasn’t thinking clearly. I spent the ages of 6 to 9 terrified of house fires.

My grandparents lived in these houses.

These are the first interiors I lost access to.

After the houses were sold, we rarely drove past.

///

I had the same room in my parents’ house from the time I was born until my mother moved out in the summer of 2019. It had lots of different wallpaper over the years, and in the beginning it had this insane shag carpet that dated from 1976, when it was built. When I was a child, I really hated this carpet. And so anytime I would drop something on the carpet, I wouldn’t clean it up. I would just rub it in.

In the 1990s, my parents put this house on the market and I was very upset. Part of me wanted to move, but at the same time I hated the thought of someone else in my room. I wrote my name all over it. I wrote –

Becky McFadden, Becky McFadden.

I wrote it in this closet and under this window sill and just so we’re clear, I’m revealing to you what I was called as a child, but that doesn’t make it okay for you to call me that now. I wrote in pencil because I wasn’t that naughty a child.

I wanted to put my mark on this room. So that even if someone else lived there, this would still be my room.

I was the last person in my family to be in this room. Because somehow the day we moved out, I was the last person to leave. It wasn’t at all planned this way, but that’s how it happened.

“The impact of a room on our memory can be forceful…The space is internalised as an embodied experience and the body scheme and its basic system of orientation (front and behind, above and below, left and right) is projected onto the room and its perimeters. A memorable room becomes part of me and I leave bits of myself in the room.” – Juhani Pallasmaa, The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses

Picture your childhood room. What does it feel like? What bits of yourself did you leave there?

Movement II.

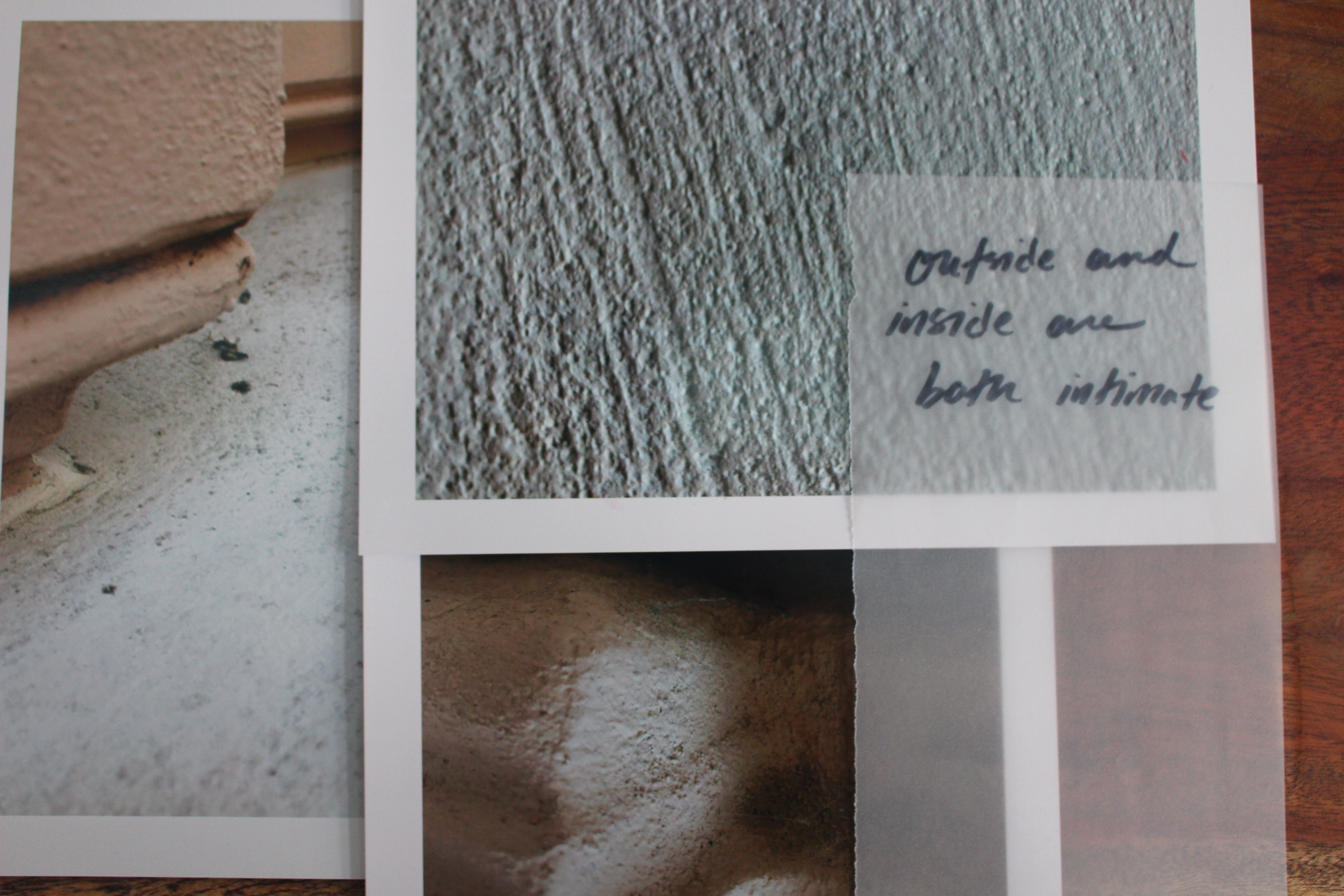

“The solemn geographies of human limits.” – Paul Eluard, Les Yeux Fertiles

“Outside and inside are both intimate, they are always ready to be reversed, to exchange hostilities. If there exists a border line surface between such an inside and outside the surface is painful on both sides.” – Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space

Close your eyes and try to picture the outside of your best friend’s house.

Can you do it?

I had never thought about this, until I went looking for a building I used to spend a lot of time in over 10 years ago. I know what street it’s on. It backs onto Stromovka park.

I walked up and down the street one day last November, looking at the buildings on this street, photographing them. Trying to remember which one it was.

I remember thinking at the time that it was a very nice building. Now many of the façades have graffiti. I don’t remember there being graffiti. I supposed I could have asked my friends who used to live there, but we’re not really in touch anymore. I tried to figure it out by myself.

My friends used to throw me the keys.

From the window.

This means I would have spent a lot of time looking up at the building.

What did it look like?

I remember the interior very well, particularly the main room, which is where I spent most of my time. You enter the room, you enter the flat here. There was a desk there. The kitchen, there was a couch, a nicer couch than that purple Ikea couch, the one everyone buys for their first apartment. It was sometimes here and sometimes here. Sometimes there was a table here. And sometimes this was a stage. And there were three windows. I can see all of this very clearly.

But none of it helps me know which façade contains it.

///

What does the outside of your building look like? Do you remember the outside of every building you’ve ever lived in? What they felt like to touch? What it was like to lean out of the windows of every home you’ve ever lived in? How the air smelled, in that neighbourhood, the quality of the light.

Sometimes I think I stay in Prague because of the quality of the light.

Movement III.

“But within, no more boundaries!” – Jean Tardieu, quoted in The Poetics of Space

A few years ago, I started taking detailed photos of the surfaces of buildings. I love the way that they are sort of worlds in themselves, very specific terrains. Sometimes, I am struck by their contours, by their resemblance to flesh. Taking these photos is a way of becoming intimate with a façade when that is all you have left. When you can’t get inside anymore.

It’s hard to make a façade inaccessible, they are kind of inherently open access. You can’t restrict people, really, from a façade.

///

I started dancing like this because I lost access to a space. It was an arts space in London and it broke my heart. This is not an exaggeration. It used to be a town hall. And for about two years, I got to spend a lot of time in it, doing all kinds of things that are not usually done in town halls, but perhaps should be.

This building had the most beautiful art deco staircase. I spent a lot of time dancing in it.

Now this building is being turned into a hotel. I can’t go there anymore. I can’t go to what it was. I will be able to go to the hotel, but I will not be able to dance. At least not in the staircase.

I took my dance from that staircase in London to another arts space in Prague. It was not far from here, opposite Vystaviště. In that building, I turned that dance of the lost staircase into a dance I could do anywhere.

Into an elegy. I used to think that elegies were about sorrow and death, but when I was working in that second building, the one not far from here, I learned that actually elegy is just any topic viewed from the poet’s perspective.

I danced an elegy for that staircase.

And now I have to dance an elegy for that second building, the one not far from here.

The one where a fan placed in a hole in the wall of the theatre threw a beautiful pattern of light against the opposite wall. I used this effect in a performance once. I danced the elegy for the staircase as the blades of the fan spun.

When I learned that space too would close, a building broke my heart for a second time.

“Part of architecture’s ideological work in capitalist society involves helping people to acculturate to capitalism’s unsettling demands.” – Daniel M. Abramson, Obsolescence

Does this mean I must acculturate to precarity, to impermanence?

Does this mean I must acculturate to heartbreak?

Has a building broken your heart? Did someone else decide it could no longer do what it was doing?

CODA

“And how many doors were doors of hesitation? The door scents me, it hesitates.” – The Poetics of Space

When I was studying theatre, a professor introduced the concept of liminality as a provocation for a task, a little performance we had to make.

Liminal: occupying a position at, or on both sides of, a boundary or threshold.

“The door schematises two strong possibilities.

At times, it is closed, bolted, padlocked.

At others, it is open, that is to say wide open.

A very slight push! And our fate becomes visible.” – Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space

There is a third possibility though. There is the threshold. One foot on each side.

A long time ago, before I had ever been to this city, someone told me, or perhaps I read somewhere, that Praha is derived from “práh.”

Práh: threshold, brink, verge.

One foot in, one foot out. One foot in, one foot out. Here, not here. Here, not here. Here, not here. Always here and never there again.

“For we are where we are not.” – Pierre-Jean Jouve, quoted in The Poetics of Space.

For we are where we are not.

Are we?

Are you?

Am I?

Where are you?

Where are you?

Becka McFadden is an artist based in Prague, Czech Republic. As artistic director of Beautiful Confusion Collective, she makes performances at the intersection of dance, theatre, visual and live art for theatres and sight-specific locations. Her projects include Black Dress, Movement/Architecture and Stories of the Present War. Becka holds a PhD in theatre and performance from Goldsmiths, University of London. She also works as a translator from Czech to English, specialising in the arts and architecture.

Absent Interiors is a project from the Movement/Architecture series and was created with support from Art District 7 — Prague 7 and Cross Attic. Photos by Svetlana Lopato, Becka McFadden, Paul Wade and Cezary Żemis. Music by Stuart Moore.