TT Journal, ISSUE 5, 20th January 2023

By David Spittle

The dreams do happen –

and there is no ‘home’ we come to

– but on this earth, and open to its powers

A recognition of the ghosts that guide us.

Lee Harwood

1.

This will move in order to cohere. It is about an experience I had watching a film at home. It will not get to the point. It was my introduction to a new filmmaker. As you are reading this your eyes attempt to pin a rolling focus and, as you go, across letters-as-words, in the going, they scan to the end of beginning again. I was sat at my desk, the curtains were drawn. It is an experience of. Drawn from one side to another, one film calling to another.

I am at home. This will be about back and forth. I should go to sleep now but I click play on the window. This will be a conversation with a filmmaker whose film I am just about to watch. I am alone, the curtains were never drawn. The filmmaker has just founded a company, Black Zero, that will share avant-garde films as home releases, curating experiences not unlike the one I am about to have. Histories of film that have not yet become embedded histories, films that need to be seen. Homes that become houses of light. The curtains were never drawn, it was an aspirational figure of speech: I have a pull-down blind. A square of red. I watched the film about a year ago. Moving on.

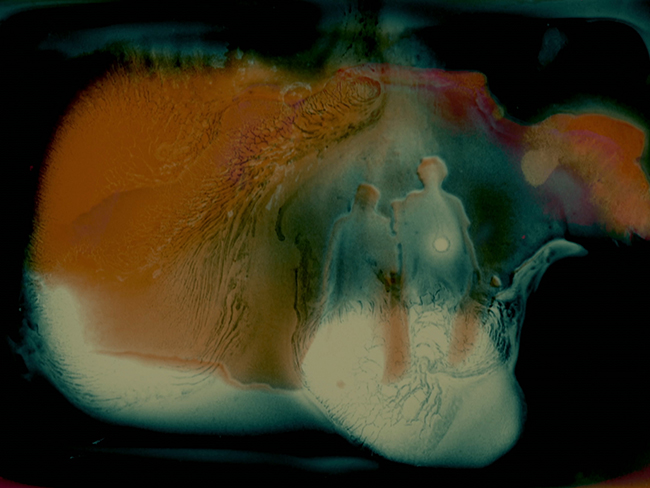

In split screen, I watch the kaleidoscopic pulse of colour: a psychedelic Rorschach test rearranging itself like rotating petals, hands, striated muscle, a naked body doubling, mirrored, drawing the eyes into a game of revealing and concealing; gestural shifts in colour and shape tease me into trying to decipher a form, a form that seems increasingly to be the forming of my own comprehension.

My attention laid bare and returned upon itself. Faces double in sequinned geometry, the sensual clasp of hands that caress flesh in the turn and tilt of patterned symmetries and, though the colours flush in polychromatic waves, a lusty red dominates. Is it lusty? Or does it become threatening, ominous. In the background of the accompanying audio, underscoring a fluttering violin score is the steady medical beep of a heart-monitor.

To encounter my own encounter, a haptic thrill that draws me further into the viewing experience in tandem to my becoming aware of that experience. It is an awareness that doesn’t occlude or distract from the experience but intermittently moves through it like a magician stopping to reveal the secret only to deepen its mystery.

As the other side of the screen illuminates in a silken elongation of bodies, my attention moves between one side and its colours, and the other side and its shapes: to feel sight as a dance between light and form, and that distinction – between ‘light’ and ‘form’ – as a contested site (sight) of exchange that soon renders any distinction an imposition. Circulatory rhythms of both (one in the other) now return to me the sensations of my own perception as inextricable from, and in extension of, the body.

I am sat tense, staring into a split square of screen. What I see is the cumulative sensation of how I see. Embodied flux: the passing appearance of a felt movement. Not unlike the focused attention of ‘mindfulness’ in a body-scan through which close and meditative awareness is selectively brought to areas of the body, or conversely in the shock of cold water, this apprehension of felt movement reintroduces me to the physicality of perception, of being moved.

In his incomplete manuscript, The Visible and the Invisible (written in 1964, first translated into English in 1968), French philosopher of Phenomenology, Maurice Merleau-Ponty built upon Heidegger’s notion of ‘being-in-the-world’ with his own concepts of ‘embodied perception’:

caught up in the tissue of things, it draws it entirely into itself, incorporates it, and , with the same movement, communicates to things upon which it closes over that identity without superposition, the difference without contradiction, that divergence between the within and the without that constitutes its natal secret.

This convergence of outside and inside without contradiction is also how the Surrealist André Breton described a surrealist state of perception:

it is possible to bring forth to the light of day a capillary tissue without which it would be useless to try to imagine any mental circulation. The role of the tissue is, as we have seen, to guarantee the constant exchange in thought that must exist between the exterior and interior worlds’.

No fixed perspective but its glancing illusion as the split / spilt fluidity of a suggestion, only ever arriving in the modulation and contingency of movement. It is a visual way of making meaning innate to the mechanics of human vision: a process dependent on tiny movements of the eyes (known as saccades) that jab in adjustments to our gaze, allowing the fovea (a depression in the inner retina layered with tightly-packed cone photoreceptors) to direct and re-direct focus.

In this heightened state of absorption (not an ‘escapist’ mode of passive familiarity nor an ‘antiabsorbitive’, to use the poet Charles Bernstein’s term, critique on the artifice that constructs such familiarities), the film nears a kind of therapeutic mysticism.

The outline of lovers in a fun house mirror. Light becoming form and form revealed by light and, in a blink, newly alive to becoming in and of the formless reimagining of form.

Naked bodies and waves of light or naked light and bodily waves; the interplay (and interdependence) further highlighted in the visual dialogue induced by split screen. Transfixed, I start to recognise the physiological effect the film is having on me. I’m just watching it on a laptop but its hypnotic, almost rapturous, force keeps me pinned to the screen.

It’s just beginning. Now it’s started to work again. The visitation, was it more or less over. No, it had not yet begun, except as a preparatory dream which seemed to have the rough texture of life, but which dwindled into starshine like all the unwanted memories. There was no holding on to it.

John Ashbery

After it finishes, closing the laptop, I pad quietly downstairs (it’s gone midnight and my partner is asleep) to pour a glass of water. The heightened feelings begin to recede and I am returned to bumbling and more prosaic meanderings of perception…mingling of half-baked thoughts and disinterested looking (mildly contemplating the distinction between looking and seeing and back, again, to distinctions: the cold and hard delusions of this and that) and, inevitably, into tiredness and the yawning practicalities of tomorrow. It suddenly seems so strange and so magical to have experienced the unfamiliar and transformative depth of this film within the familiarity of home.

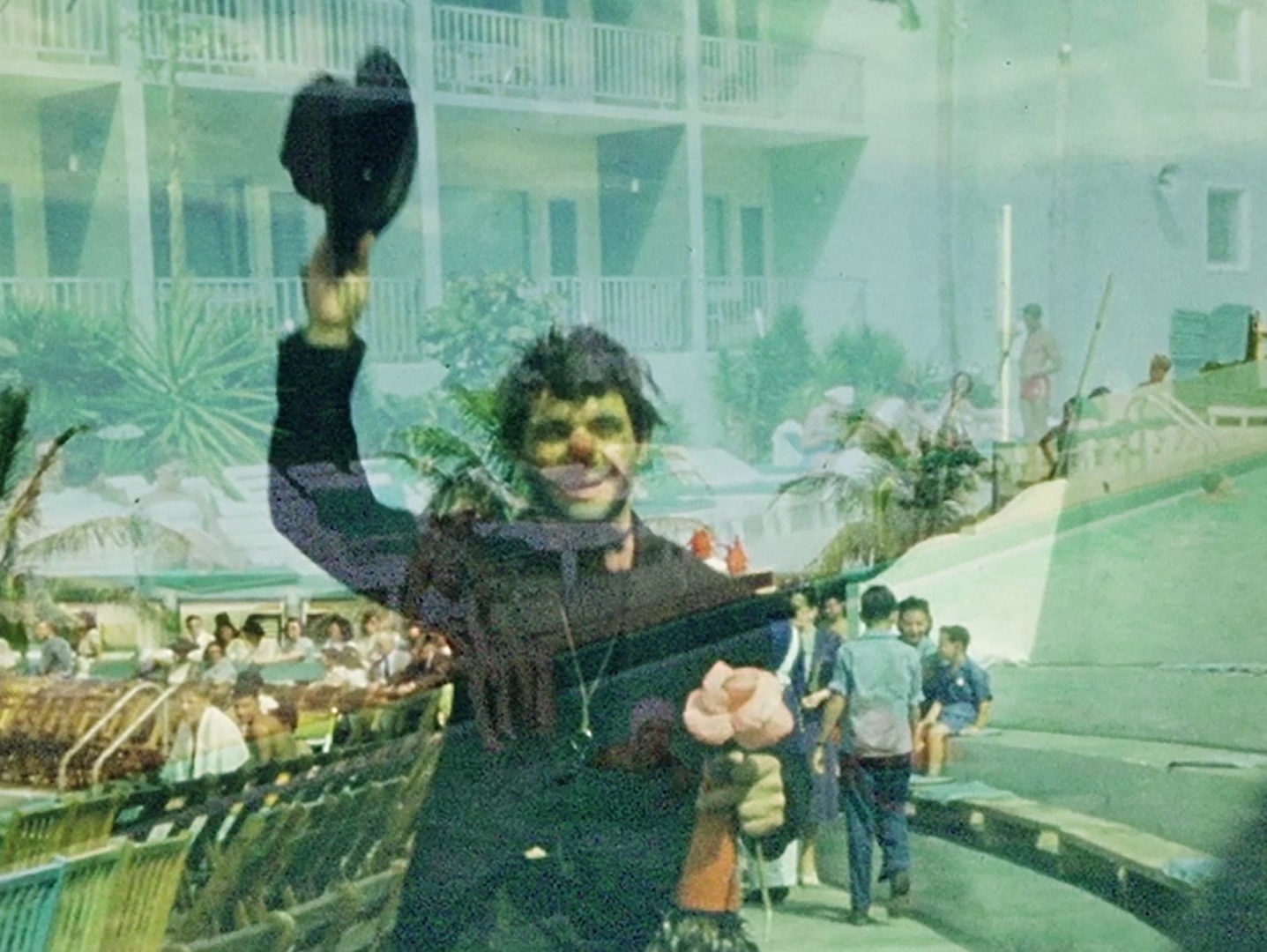

The film I was watching was Stephen Broomer’s Resurrection of the Body (2019), a film which (unbeknownst to me at the time) conjures an imagined sequel and conclusion to John Hofsess’ Palace of Pleasure (1967), a film that Broomer restored in 2008. In his article ‘John Hofsess: Man in Pieces’, Broomer relates:

[i]n anticipation of the film’s release [Palace of Pleasure], Hofsess wrote a manifesto on contemporary life, the psyche, and society in which he concluded, “man is a process and the truth is in flux.” Through this art he was putting himself together, a process of becoming.

It was this sensation of flux, process and the mythic sense of the psyche (a deified representation of the soul in flight) that felt so experientially present in my viewing of Resurrection of the Body.

2.

Stephen Broomer has been making extraordinary films for just over a decade and they are – at least for this viewer – among the most mysterious, ecstatic and mutable works in contemporary experimental film. His artistic energy and expansive vision also extends into film preservation, scholarship, video essays, poetry and an evolving pedagogy that extends passionately from all of these combined and conversant fields.

From his first 16mm short, Manor Road (2010), in which a static long shot reveals trains gliding in and out of the gloom beneath a changing horizon, there is a keen awareness of the experiential, hypnotic and transformative properties of film.

With around 44 films, I would not be able to, nor want to, reduce Broomer’s constantly shifting work into a reductive summary of preoccupations, aesthetics, techniques or patterns of interest .They seem to be passionately searching for new and unknowable encounters, intuiting new ways of perceiving or of perceiving perception and, through that, an evolving and propulsive pursuit of mystery. They are, in short, unafraid of celebrating the visionary in histories and hallucinations of whatever might constitute the personal ghost-chemistry of vision.

There is the palimpsest of dereliction in Christ Church St. James (2011) that scratches itself into a ritualistic séance of saints and rubble, the playful mise en abyme of frames and light in Pepper’s Ghost (2013), and the propulsive alchemy of interrupting and evolving the image through chemical or physical means in Jenny Haniver (2014). More recently, Broomer’s work has ambitiously taken aspects of found footage into a truly wild conceptual, as well as aesthetic and experiential, reimagining of form.

In 2017, Broomer made the staggering feature-length Potamkin. It took re-photographed sequences from the films that the pioneering film critic, Harry Potamkin (1900-1933) had written on and then brought them into a feverishly coalescing biography of strobing fragments; a life reimagined through its burning house of light, as if through the mystic transmutation of cinema history Potamkin’s spirit might become a newly luminous presence. This was followed by three equally astonishing films: Tondal’s Vision (2018), Lula Faustine (2020) and Fat Chance (2021). All of which ignite their whirling invocations around a mythic reimagining of specific historic texts, figures and what becomes, in each film, the mutably continuous presence of a kind of afterlife; a guiding passage in the rapid flux of light and emulsion.

Between Potamkin and the connected films that followed, in 2019 Broomer made Phantom Ride (it was also the year in which he made Resurrection of the Body) which took the home movies of Elwood F. Hoffmann (1885-1966) and collaged a dexterously layered film from dreamy family holiday footage, endless driving around America and the haunted superimposition of roads crossing roads while time is crossing time in a record of memory and traversal. What begins as an elegiac nostalgia grows into a soaring visual hymn to loss and belonging.

A repeating soundscape of almost angelic recurring high notes becomes, like the passing landscape, a generative repetition that reveals (like the writing of Gertrude Stein or ambient music, drone and the best of slow cinema ) the variegated difference that accrues in repetition, the deepening sense of awareness and of time and place. The familiar loses its semblance of familiarity, the home movie becomes a twisting dream song and there is, in Broomer’s restless layering of road and sky a complex feeling of home predicated on movement.

When I discovered that Broomer was starting the company Black Zero, curating and creatively presenting the distribution of avant-garde films for home release, not only did it make perfect sense (extending his work in preservation and restoration, in addition to his scholarly expertise) but it also felt poetically apposite. The ‘home movies’ that Broomer’s Phantom Ride so intuitively conducts, as though in transportive conjuring, demonstrates an imagination (and its parallel exploration and expression of perception) deeply sensitive to the unfamiliar plurality, mystery and tumultuous connotations that might substantiate ‘home’.

David Spittle: Within the context of Canadian avant-garde film, what does ‘home video’ or ‘home movie’ mean to you?

Stephen Broomer: To my mind these are two distinct but integrally related forms. The home video and the home movie are separate stations of the same framework: personal inscriptions of everyday life, made for the most intimate audience, like snapshot photography. What differentiates them is material: the home movie was contained in a short span of 50’ or 100’, it captured light and in doing so captured an organic ‘shadow’ of quotidian experience. Home video, by contrast, expanded running times, so much so that many children of the 80s who were lucky enough to be chronicled in family videos can now look back on far too many hours of nothin’-happenin’. But home video also splinters in its meaning, because like the home movie, it is a production mode, recording and inscribing memories; but it’s also the term we use for the mass proliferation of home viewing practices for movies. The home I grew up in had a heavy debt to the VCR, which we got when I was three years old and which became an immediate window onto culture and entertainment. The Canadian avant-garde film has a long history of engagement with the home movie: we see home movies and snapshots in R. Bruce Elder’s The Art of Worldly Wisdom, the great formative diary film of the movement, which came to define so much of what came after it; and we see that resonance in other ‘home movie’ focused works, from the snapshot bias of Richard Kerr’s On Land Over Water, to the family-home imagery of Barbara Sternberg’s A Trilogy, to the diaristic streams of Mike Hoolboom’s Frank’s Cock. It becomes a kind of heritage—and we can see a direct link, formally, from Elder to Sternberg and Hoolboom. There’s also a home movie aesthetic present in work that runs parallel to this movement, like Rick Hancox’s Home for Christmas. And in more contemporary work, home movies are the occasion for works by filmmakers like Izabella Pruska-Oldenhof (my I’s), Louise Bourque (Imprint), and Rhayne Vermette (Les Châssis De Lourdes). But for all of its engagement with the home movie, and despite the fact that home video has been around and accessible for the past four decades, it has been rare to see this work in a home-accessible context, remedied a bit in recent years through bootlegs: in the case of official releases, the emphasis has always been on an institutional context, for instance, the series of compilations made by CFMDC in the 2000s, and their box set releases dealing with canonical filmmakers (Chambers, Wieland, Rimmer). So in this sense Black Zero will often be dealing with images of ‘home’, images that are intimate and personal, and bringing it all back home, righting the balance between watching work in the impersonal setting of the theatre or gallery and the personal space of the home.

DS: What are your formative memories of Home viewing?

SB: My earliest memory of home viewing was watching what I think must have been a PBS staging of Peter Pan when I was three years old in the basement of our home in Peterborough. For a year we lived there, the only time I’ve ever lived outside of Toronto. So there I was in a temporary home, I imagine with a rented VCR, watching this story about the freedom of the child-rogue; I’d later get it hopelessly confused with True Stories, which we would often rent and watch, again and again, that same year. That gave way to richer and deeper experiences, watching videotapes borrowed from the public library, and what I remember about home video is that I used to have a limitless capacity for watching movies I liked over and over. At some point I started doing what I could to track down the tapes being issued by Mystic Fire Video, and that was where my awareness of alternative movie distribution came from, and what a boutique label was. Back then, I never thought, “I want to do that.” But I watched their tapes of Maya Deren and Shirley Clarke films and said, “I want to do that.”

DS: With the exciting launch of your multimedia publishing company Black Zero (specializing in Blu-ray Disc releases of Canadian experimental films from the 1960s onward), could you say a bit about some of the origins or influences that inspired this development? What role do you think the home-release of physical media has in regards to avant-garde or experimental cinema?

SB: I started restoring and preserving experimental films when I was in my early 20s, as an independent. At the time, the market that existed for what I was doing was mostly one-off shows at galleries and cinematheques: I had no thought to do VOD, or to put out a disc. I don’t know if I found the thought of doing so intimidating, but it wasn’t a priority. But I was always aware that there were good things coming out, from companies like REVOIR, Milestone, Facets, Image, Flicker Alley, Kino. I was really inspired by Bruce Posner’s work, especially Unseen Cinema, which is an epic undertaking and which weaves context and work in a way that was useful to me as an educator but vital to me as a viewer. It’s nothing new to be putting experimental cinema on home video, but I think there’s a lot of room for growth in this regard, of context, of giving context to mysterious objects, of offering those who want to really follow and understand complex works an opportunity to do so with commentaries, liner notes, documentaries, interviews. For me a lot of this comes out of inspiration from Posner’s work. I could also say the same of Pip Chodorov’s work with his team at REVOIR.

DS: What are your thoughts on the physical media market, boutique labels and the ‘home release’ and does that translate into, or influence, your vision for the development of Black Zero?

SB: I think we’re in a golden age for the home video market: a massive amount of consumer choice, a mass proliferation of experiences, many different ways to have that experience (be it streaming or physical media). There’s a greater sense of specialization among companies, and that reflects the specialization of consumers. As consumers we aren’t left wanting, and whether you have an interest in things that are off the beaten path, or you want high-resolution copies of once-rare studio films, there are so many experiences to have. There are real treasures being discovered that once may only have circulated, if at all, as bootlegs, low-quality videotapes, a handful of worn prints. We’re now seeing restorations of them that give them tremendous life. The other night, Mark Toscano was talking on his Remains to be Streamed broadcast about how he’s just done a restoration of Timothy Carey’s The World’s Greatest Sinner, and how those who can now see it in this way—what I’d imagine is the best possible quality, as good as it ever looked—will be able to appreciate it more, as a work of freedom and imagination. Isn’t that beautiful? That resonated with me deeply. I thought the same thing a few nights ago when I watched Winterbeast, a wonderfully messy regional horror movie that Vinegar Syndrome issued last year, made modestly and one gets the impression, by a circle of friends, another kind of home movie, and its sloppy continuity at maximum quality became more dreamlike. To answer your question, this is what I want, to make it possible for people to experience and appreciate these remarkable films that have meant so much to me. Through Black Zero, I only intend to release films that I connect with in that way. In this sense it’s a curatorial project and an act of critical reclamation: I’m making a case for the inclusion of works that have been neglected.

DS: In regards to the creative and curated nature of the best multimedia releases, you seem to be uniquely well positioned (as not only a filmmaker but a critic, poet, video-essayist, preservationist and teacher) to imagine how the home-release nature of disc distribution might evolve and, additionally, how the presentation and capacity of such a release could be more artistically conceived. Is this part of your enthusiasm for your project? I was thinking, also, in relation to your phenomenal series of video essays, Art & Trash!

SB: I’m optimistic that home video distribution will stay the course so long as supply chains hold up, so long as playback systems are still manufactured, and writeable media is still available. And that means that we have an opportunity to enrich our film culture through context. The home video market, as it is right now, has tremendous promise in terms of bringing historical and critical context to the attention of consumers. Some companies, like Severin, Vinegar Syndrome, Criterion, have understood the importance of deepening context, which is also sometimes about feeding fan expectations and honouring makers. A home video release of a film is not the film itself. It’s a high-quality reproduction, like the reproductions of paintings you’d find in a museum catalogue. And like a museum catalogue, it’s also a container that can host many ways of watching and understanding a given work. It can be an extension of the whole discourse around a film. Although we started collaborating after I’d already begun work on the special features of Black Zero, the author and filmmaker Kier-La Janisse, who produces content for Severin, has been a particular inspiration for me in this regard: she has a visionary understanding of how you can enhance the experience of a film through the contexts given by interviews and video essays and commentaries. That’s my ideal as a consumer, and it’s what I hope these discs achieve.

DS: Your first wave of releases includes John Hofsess’s Palace of Pleasure, Keith Lock’s Everything Everywhere Again Alive, and Arthur Lipsett’s Strange Codes.

What led you to these these films, are they a fair indication of the direction you want to take with Black Zero? To what extent do you think about the long-term curatorial sensibility of this project and what, if it’s not too clumsily reductive, such curation aims to reflect, embody or achieve?

SB: These are films that I picked up through the course of my adult life and that had a profound impact on my ideas as a filmmaker, as an artist, as a critic. These are restoration projects that I pursued, and they have qualities shared between them that might tell you a great deal about me and what I value. John’s film is about the possibility of therapeutic healing through psychedelic light, subliminal imagery and sensual colour; Keith’s film is about retreating from civilization to build something new, freed from all the hangups of urban life; Lipsett’s film is about having something strange crawl inside of your heart, like soldiers climbing into the Trojan Horse. These are themes I deeply identify with. So in that sense these releases are a fair indication of the nature of my investment in experimental cinema. For me the curatorial sensibilities of this project aren’t bound to this project, or to curation, they’re a way of living because they reflect how I’m living, guided by love and fascination. The works reflect that. They’re a discourse, asking complex questions of us. The projects we have planned will extend and expand that discourse to include other, profound ideas, on fate and the course of history, on nature and subjectivity, on flesh and the ghostly light of rephotographed, processed, transformed visions. I suppose if I’m looking to achieve something, it’s not the condescension of educating and informing, but the act of trading visions, exchanging visions, that’s what home video can be just as parlour filmmaking once was. A film as intimate and particular as Keith Lock’s Everything Everywhere Again Alive can now be watched by a total stranger on the other side of the world, and they can approach it with an open heart and find something in it that touches them. That’s why I want to use home video as a platform for sharing work, it opens intercultural discourse, it creates new bonds among strangers, and each case can be a storehouse of history.

David Spittle is a poet, filmmaker, and essayist. He has published three collections of poetry: Rubbles (Broken Sleep Books, 2022) All Particles and Waves (Black Herald Press, 2020), and B O X (HVTN, 2018). He has also published a collection of interviews, Light Glyphs (Broken Sleep Books, 2021), with poets on Film and filmmakers on Poetry [including Guy Maddin, Andrew Kötting, John Ashbery, Iain Sinclair]. Spittle’s first short film, Light Noise, was funded and broadcast by the BBC, with subsequent documentary work funded by the Austrian Cultural Forum. His film ‘Lazarus Taxa’ was screened at Braziers International Film Festival, 2022. Spittle holds a Literature PhD on the poetry of John Ashbery and Surrealism. He continues independent research across Poetry, Film, and Noise. His films can be viewed on Vimeo.

Black Zero website: http://www.blackzero.ca/

You can also read more from David Spittle in Tangible Territory journal (issue n.2): https://tangibleterritory.art/journal/issue-2/david-spittle/