TT Journal, ISSUE 6, September 2023

By Rosalyn Driscoll

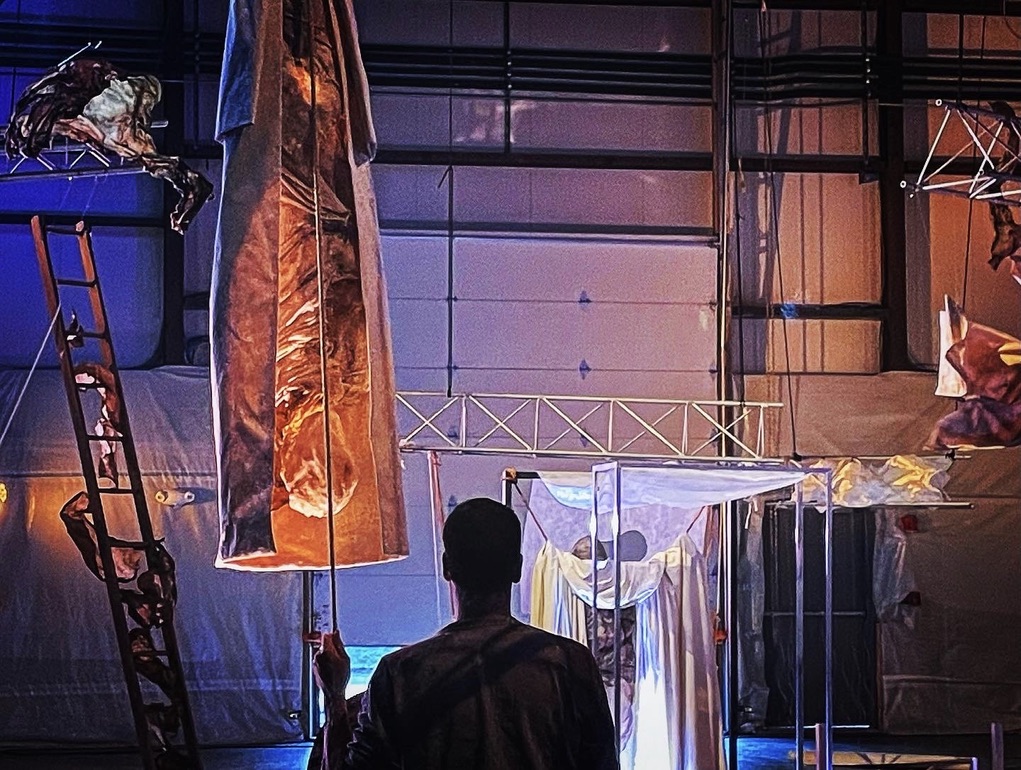

Visitors enter the vast space of a former warehouse filled wall to wall and floor to ceiling with sculptures, hanging, standing or lying about, alongside materials like rope, cloth and a tank of water. Metallic disks, aluminum trusses and twisting pieces of rawhide activate the vertical dimensions of the space. It looks like an art installation, stage set and artist’s studio.

A dancer moves through the installation, improvising as he goes, exploring possibilities for interacting with the sculptures and raw materials. He crawls through, climbs into, wraps himself in, moves and changes them. He assembles, disassembles and connects things. He feels their weight, flexibility and hardness, sensing the opportunities they afford his physical curiosity.

This hybrid art installation-dance performance, called how many times, is collaboratively developed by dancer-choreographer Paul Matteson and myself, visual artist Rosalyn Driscoll. Over several years we developed iterations of this project, which conceives each performance as a lifetime. His interactions with the sculptures and the space are embodied metaphors for the choices we make and the challenges we meet as we move from birth to death. These photographs are from seven evenings of performance, June, 2022, in Northampton, Massachusetts, USA.

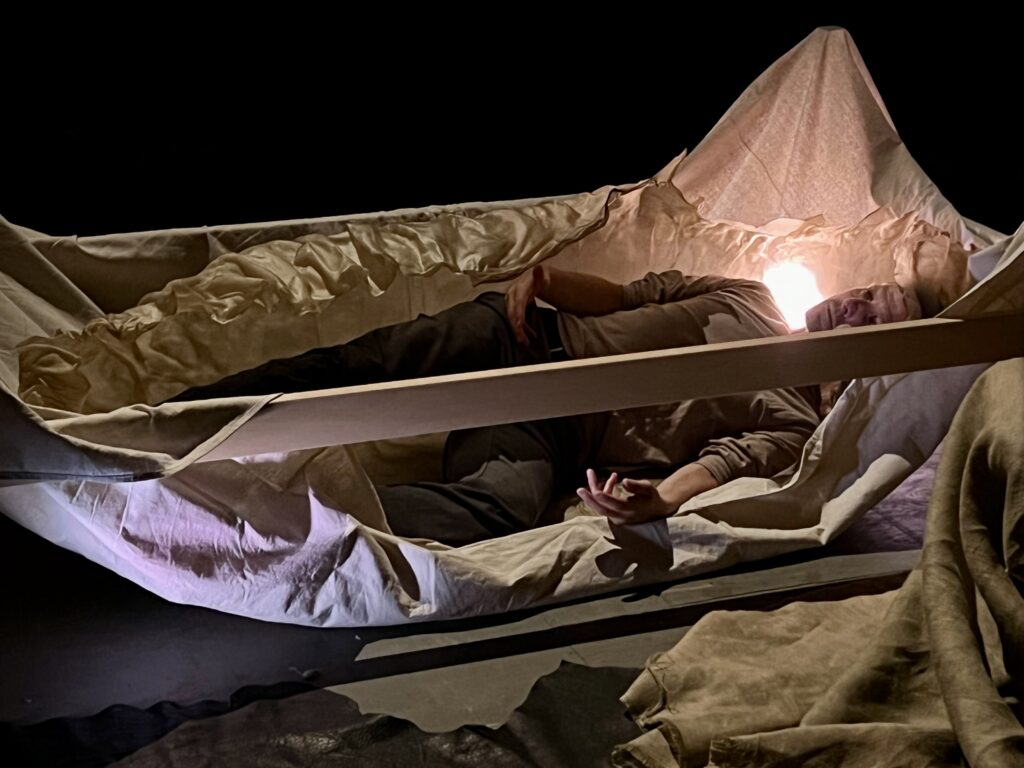

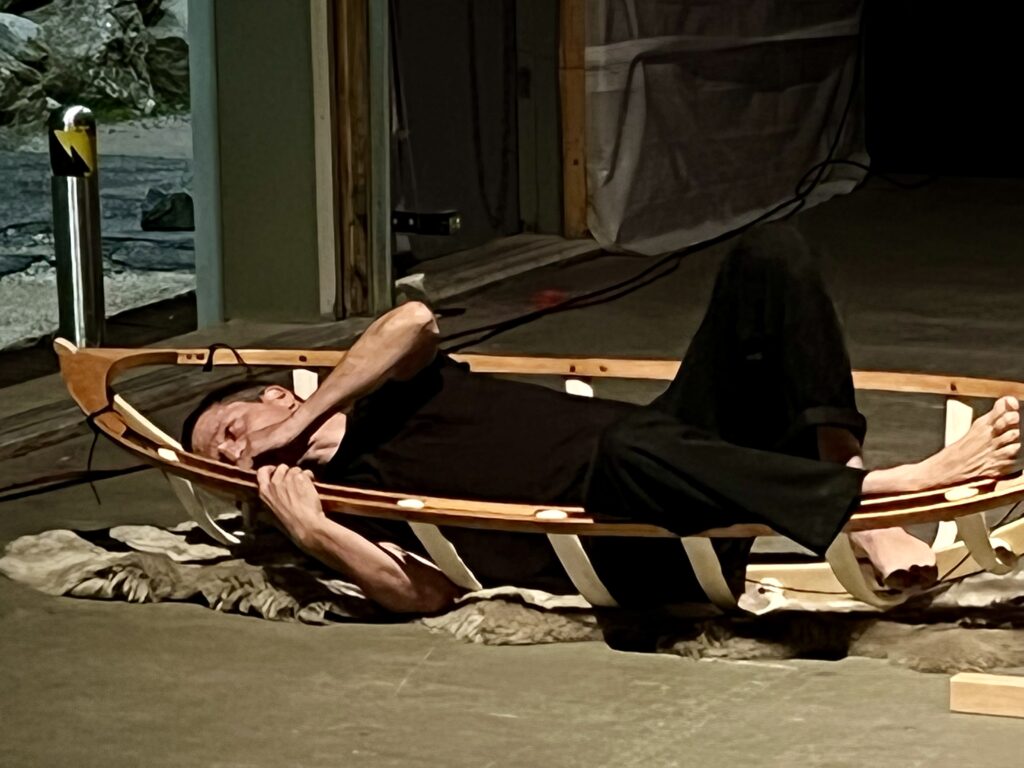

There is no choreography, no plan for what happens each evening. We trust each other’s genius to respond to the conditions on the ground. True play depends on freedom from limitations, trust in one’s intuition, and curiosity. What Matteson is doing is not dance but rather physical, sensory inquiry—in other words, play. Guided by his curiosity, his instinct for novel movement and his finely tuned body, he sets out to question everything he encounters. Using hands, feet, face and his whole body, he feels the potential and the limits in each element or material: Can it hold me? Can I enter it, ride it, immerse in it? Does it tear, crumple or break? Does it spin, fold, rise or float? He tests, challenges and plays with everything in his path. His actions are improvised, spontaneous, intuitive. He is bodily, sensory intelligence in play.

He is an artist grappling with materials, a person encountering matter, a moving sculpture in a field of sculptures. His actions animate them as they resist, accommodate and alter his motion. He moves and is moved by them, shapes and is shaped by them. His actions of lifting, pushing, pulling and rolling are familiar, but as he interacts with these unfamiliar sculptures in the context of a performance, his gestures become original and moving. His concentration and commitment reveal the deep purpose of play: genuine discovery occurs when the outcome is unknown.

He is aware of the metaphorical import of his actions. He knows associations are triggered by immersing himself in water, climbing on a sculpture, turning a door into a bed. He trusts people will find meaning and inspiration in his deep curiosity, creative impulses, and continuous transformation of matter and, above all, of self. His actions reveal that the true nature of bodies, things and selves is becoming.

Actions and feelings fuse. Wildly contrasting emotions emerge and disappear. He creates a storm of torn paper and then tenderly settles the crumpled pile in a boat. He delicately touches a sculpture, then dashes around setting everything in motion. He becomes different kinds of creatures. He plays, works, ages and dies. He is an artist. He is everyman.

I made the artworks to offer affordances for Matteson’s embodied inquiry. Each performance I provide Matteson with a range of elements—from simple materials like rope, cloth and water, to odd sculptural fragments, to completed sculptures—all grist for his mill. He draws pieces together and pulls things apart, creating new artworks and changing the installation. The entire space is activated, disrupted and connected by the end of the evening. Between performances, I assemble the artworks and materials into a different configuration, making a new world for him to discover each evening.

Watching him improvise with my sculptures and materials, I experience my works in unexpected, revelatory ways. No longer precious, isolated, inviolate or inanimate, they become open, interactive, alive. As he plays with their endless possibilities, they are no longer mine. As I watch him do things with and to them that I never dreamed of, I release them, over and over, to his creative spirit. This is key to the nature of play and to the creative process: intentional non-attachment. Delight in not knowing.

Sound and lighting are also improvised, responsive to his movement and activating him, the objects and the space. Wireless theatrical lights are moved by the artists to create changing dramatic effects. Over the days of the performance-exhibition, everything changes—visually, structurally, emotionally and energetically.

The usual boundaries between viewer and artwork, audience and performer are fluid. People may come, go and move around and through the installation and performance at will. Their experience of the artworks is enlivened and deepened by Matteson’s movement. They undergo changing degrees of intimacy and distance; intention and surprise; resistance and insight. All this motion generates shifting, multiple perceptions and meanings for the artists and the audience.

how many times animates body and matter. It invites new levels of uncertainty, creativity and participation. It fills the space with life—human and other-than-human. It offers agency to the sculptures and materials, the dancer and the audience. how many times creates a new kind of relationship to art, grounded in interaction, movement and sensory experience.

how many times performance can be watched here:

Rosalyn Driscoll is a sculptor whose work centers in the body. For ten years she made and exhibited tactile sculptures, writing about her discoveries in The Sensing Body in the Visual Arts (London: Bloomsbury, 2020). Her focus on sensation, kinesthesia and proprioception, and her desire to animate her sculptures led to this collaboration. She is a core member of Sensory Sites, an international collective that explores multi-sensory perception in site-specific installations. Her work has received awards, fellowships and residencies and been exhibited in the US, South America, Europe and Asia. www.rosalyndriscoll.com

Paul Matteson is an associate professor in the School of Dance at the University of the Arts. He is a BESSIE Award-winning performer whose research explores methods for generating inventive personal movement within collaborative choreography. He was a member of the internationally touring Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Company from 2008 to 2012 and has worked with David Dorfman Dance, Lisa Race, Terry Creach, Peter Schmitz, Neta Pulvermacher and others. He regularly teaches at summer festivals, including the American Dance Festival, the Bates Dance Festival, SALT Dance and Provincial Dance Theater’s Summer School in Yekaterinburg, Russia.