TT Journal, ISSUE 6, September 2023

By Dordi Strøm

– in what ways are the practices of sculpting clay, crafting scenography and writing novels similar?

During lockdown my everyday practice, as I had known it, came to a halt; the theatres shut down, I lost jobs and planned projects were put on hold. Stuck in my lock-down-studio-hideout I was forced to question the obvious: Were there other ways for me to practice as a scenographer where I could still make use of my knowledge and experience?

I have worked in a wide range of media and areas within the arts, from drawing and collage work, to ceramic art, writing, installation art and performance in public space. I think working within the arts, regardless of media, has been about making space for discovering, sensing and learning, and about understanding our entanglement to the world.

In 2021, with an involuntary lock-down-time-out from theatre work, one published novel and a second on the way, it became increasingly obvious to me that apparently different ways of practising as a scenographer, have more in common than I knew from before. I use the same ways of discovering, producing and organising my material within the framework of a text, as when discovering ontological structures and narratives of a performance. The slow days alone in my studio gave me time to study these similarities, and I realised that I needed new words to describe them – for the sake of my own practice(s), but also to challenge the general understanding of the scenographer´s and the writer´s practices as being worlds apart.

Dr. Rachel Hann´s book Beyond Scenography (2019) was one of the books I reached out for to try and come to a deeper understanding.

Play, come what may – what scenography does

In Beyond Scenography (2019) performance scholar Rachel Hann´s methodological focus is to consider what scenography does, how it “orientates, situates and shapes” (theatre) practice, rather than focusing on what scenography is (Hann, 2019, p. 5).

Starting the process of making a theatre performance, or a novel, I am open to whatever might happen, I follow my intuition, I seek, and I play. In later stages of a process my material is moulded, changed, challenged and played with further, in the theatre this happens in interdisciplinary collaborative collectives, when writing my editor is my collaborator. The work is also moulded by the immediate surrounding scenography – and what this scenography does. To me as the crafting scenographer and my collaborators, scenography happens and intervenes with the work on many levels: colours in the interior in the theatre venue, the surface of my writing desk, the weather, by gravity.

The scenographic writer – scenographics as place orientation

Hann introduces new thoughts on scenography, when making a distinction between “scenography as crafting” – and “scenographics as place orientating” (Hann, 2019, p. 79). She sites scenographer Thea Brejzek who argues that with the expansion of scenographic traits beyond theatre orthodoxies “the scenographer emerges not as the spatial organiser of scripted narratives but as the author of constructed situations and as an agent of interaction and communication” (Brezjek, 2010, p. 112 in Hann, 2019, p. 4).

I recognise this position, as a scenographer, both when writing and crafting scenography in the theatre; I practice “scenographics as place orientation” and I am an “agent of interaction and communication” playing with images and ideas that come to mind or appear there and then. I produce material for a long period of time without making judgements or selections, until I sense that my material contains what I need. I am open to whatever needs to be included, be it light or smell, sound or music. I am a scenographic writer and an “author of constructed situations” and scenes, using costume, choreography or objects. In parts where I would use video on a stage, I’m the cinematographer using projections or double exposures in the scenes that appear as I write. All these elements come together and operate as scenographics that orientate(both the writer, and the reader in) interventional acts of worlding (Hann, 2019).

Acts of worlding

Hann considers scenography a crafting of “place orientation” – and scenographics as “that which orientate interventional acts of worlding”. (Hann, 2019, p. 79)

In posthumanistic thinking and in new materialism, we encounter the concept of worlding, which in turn is linked to process philosophy and theories on human and more-than-human. Scientist and philosopher, Donna Haraway, claims that knowledge and knowledge production cannot be separated from lived life: the production of knowledge is part of an ongoing worlding. Rachel Hann quotes Kathleen Stewart who expands on Martin Heidegger´s approach to define worlding as “an intimate compositional process of dwelling in spaces that bears, gestures, gestates, worlds.” (Stewart 2011, p. 445 in Hann, 2016, p. 79).

Regarding scenography a mediator for spatial figuring, Hann also outlines how scenography “happens as a temporal assemblage that is linguistically more akin to notions of staging than set.” Hann argues that this differentiation “affords scenography a platform from which to invite intellectual bridges with other academic disciplines beyond theatre. To study scenography in the early twenty-first century”, is, according to Hann, “to study a practice that is always seeking, always implicated, within a transgression of borders, whether disciplinary, linguistic, geographic or practical.” (Hann, 2019, p. 2).

Can scenographic writing be understood as transgressing borders between artistic disciplines, such as collective theatre work and fictional writing? One thing I do feel certain of, and embrace, is place orientation as one of the key aspects of scenographic writing.

Courtesy: Galleri Magnus Karlsson

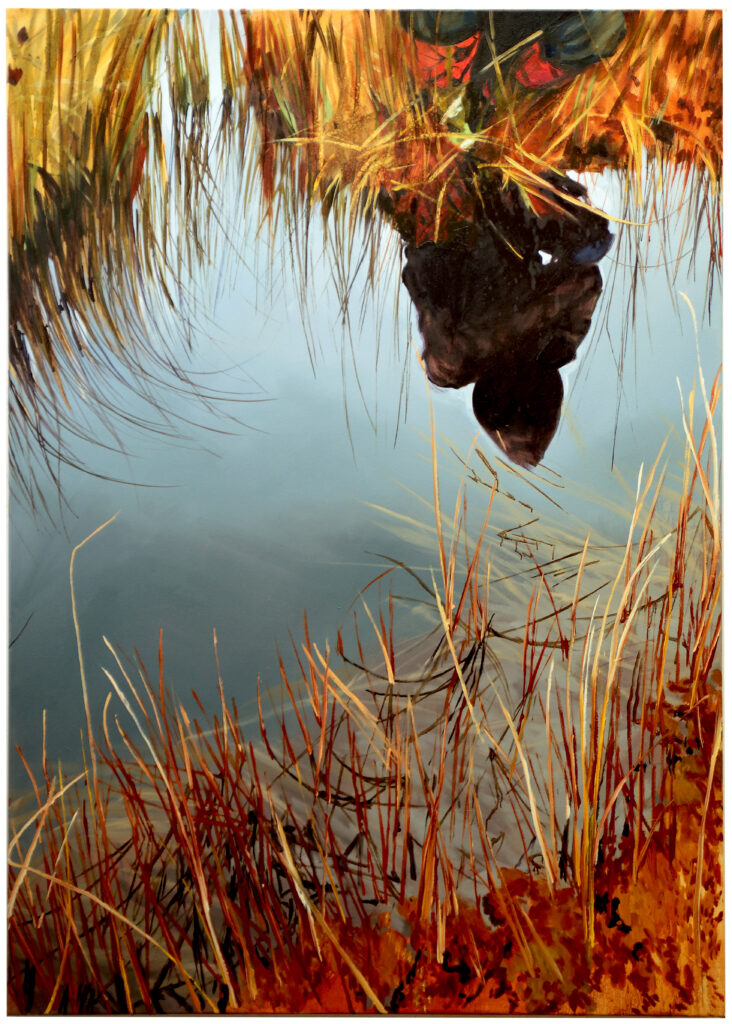

On the novel Odel and place

Sites and places in the house, on the farm and in the surrounding landscape, are often returned to, and play central parts in my novel Odel (2023). The pond in the marsh is one of these places. Up until early Viking age ponds in marshes were considered sacred sites or portals to the afterlife. They were gateways to the other side, to another parallel world. In Norwegian everyday speech a small pond in a marsh is also called an “ox´s eye”, or just an“eye”. The image on the cover of Odel, The Assistant, is a photo of an original painting made by Swedish artist Sara-Vide Ericson. Ericson´s painting has inspired the characters in the book, and also images and scenes that take place by the pond in the marsh, not far from the farm in Odel: the dog, Bowie, that dies early in the book, is buried in the eye in the marsh.

As a child I fantasised of sole wanderers crossing the mountain near our farm under the moon light – of the ghosts of farm animals sharing secrets with me from remote times – of escaped soldiers from the second world war, still hiding in the barn – of tricksters in different shapes knocking at our door (my grandmother let them into the kitchen and served them a cup of coffee or a snack before they disappeared). I had fantasies of ancestors, whose portraits hung on the old walls of the living room, and who whispered in my ear. Of herds of deer dancing their slow murmuring dance on the field outside my window at dusk, of magical trees in the garden and powerful talking plants and insects, singing secret songs made up of strange, yet familiar words.

In Odel, the fictional child Liv longs for her vanished mother, Odel. She hides, like I did, and from her hideouts, inspired by fairy tales, old folk songs and dreams, she sees, hears and smells the world outside her dwelling.

The house is a body Liv hides in. She has a secret place in the dog´s basket under the kitchen table on the floor by the tall kitchen cupboard, under the stairs in the hallway, under the sofa, under the beds. On the wall inside the cupboard in the attic, mum made a drawing, there´s a greeting from ten-year-old Odel. Odel has drawn a bird on the wall, down by the floor moulding; inside the cupboard mum has drawn a marsh warbler. Next to the bird, below the drawing, Odel has written the name of the bird, Acrocephalus palustris, marsh warbler; mum has written it in tiny little letters on the wall next to the drawing. (Odel, 2023, p. 28-29)

The landscape and the body

The knot in her neck is tight, she has to use both hands, neck hair in the knot, she pulls it, tears at hair and hair roots, the thin skin is a pointed mountain in her neck, there are more mountains, a whole mountain range, tight hair needles, she holds her breath, closes her eyes, grits her teeth, tightens her mouth in a line, the knot gives way, she sighs, exhales, takes off her scarf, hangs it on the hook, on top of her coat. (Odel, 2023, p. 138)

The above quoted scene can be interpreted as an attempt to recreate the multimodal qualities of the experience of acting out everyday actions, such as taking off work clothes and hanging them on a hook on the wall. The layered scenographic image of Odel in the hallway with the mountain range in her neck both reveals and portrays how thoughts and associations are always someplace else as well as in the present. To me, this is a concrete example of how the act of place orientating happens in the process of scenographic writing. This place orientation leaves double or sometimes multiple images in the readers’ internal landscape. In addition, for the reader, there is the experience of the reading situation as well: The sensation of a soft chair, perhaps, or a cold bus seat or moist grass, the smell of dinner from the kitchen, light summer breeze, sand on a beach, the sound of birds in the distance.

Metaphors are a common tool in fictional writing but interpreting the scene above from a scenographer´s (and not a literature scholar´s) perspective allows other words for what is at play. Hann elaborates further on Brezjeks´ statement and claims that, “if scenography happens as an interventional situation, then the orientation of scenographic traits, are inclusive of all human and non-human agents that render a place as eventful, attentive” (Hann, 2019, p. 4).

There are no mountains in the scene in the hallway above, where Odel is taking off her headscarf. But the mountain range is present – it is projected onto Odel`s neck and creates a double exposure – one might say that it renders the place (the hallway) as “eventful, attentive”. The mountains near the farm where Odel lives have been introduced in various ways to the reader earlier in the narrative and are thus present on many levels and in multiple layers at the same time, both in the book, and in the readers’ internal landscape.

When recording “the process of material acclimatisation that occurs in time”, on paper, or on my computer screen, I write whatever appears to me – the double exposure that appears in the text above, I claim, is the result of scenographic writing. Or to make a go at using Hann´s terms, I suggest that what happens, both in the act of writing the text, and hopefully for the reader in the act of reading it, is scenographics at play that “orientate interventional acts of worlding” (Hann, 2019).

The novel as a one-person-audience mobile scenographic device

Every reading experience or theatre performance is unique, it can never be repeated in the exact same way. On stage a book is commonly interpreted as a prop – outside the theatre it can also be experienced, used or understood as a one-person-audience mobile scenographic device. It can be read over and over again, each time with new or added content, such as the reconsolidated memories of the reader’s last encounter with the book.

In a novel the scenographer writer can move with the reader into new and unknown narratives unfolding in landscapes crafted of dreams, memories, futures, architectures or biology. The scenographer writer can dwell with props and objects, human and other-than-human that on a stage would appear as small details or extras. In a novel they can become centre pieces, or parts of fluctuating ongoing images and montages in constant change.

Scenographic tapestries and porous montages of images and transitions, can be fragile cloths or a weave of images, narratives and cross-references, held together by the compositions of words and sentences that shape and change the images, the dramaturgy of the story, and ultimately the physical pages and cover of the book. The process of both writing and reading a novel holds potentialities of multiple becomings and of complex worlding (Hann, 2019).

Author Ursula Le Guin opposes traditional linear narrative (such as the story of a Hero with a weapon aiming at a target or a pray) and holds up the container as a form that more than any other, depicts the human way of thinking and becoming, and one might add; the container has room for whatever the reader herself finds on the way, or brings to the reading. Le Guin compares the novel to a carrier bag: “I would go so far as to say that the natural, proper fitting shape of the novel might be that of a sack, a bag. A book holds words. Words holds things. They bear meanings. A novel is a medicine bundle, holding things in a particular, powerful relation to one another and to us.” (Le Guin, 2019, p. 34).

The longing for transcendent forms

Liv’s hideouts in Odel are secret, and they are sacred. The Rumanian historian, author and philosopher Mircea Eliade (1907–1986) argued that a “sacred place” is a spot where the sacred or holy breaks into the mundane. Each such place becomes a “center of the world” or an axis mundi, a point of connection between heaven, earth, and the underworld (Voth, 2010). Originally the word home, according to John Berger, meant the centre of the world – not in a geographical way, but in an ontological sense. Home was the place where a vertical line was crossed with a horizontal one, and therefore became the center of the world. The vertical line was a path leading upwards to the sky and downwards to the underworld. The horizontal line represented all the possible roads leading across the earth to other places. At home one was nearest to the gods in the sky and to the dead in the underworld. This nearness, says Berger, promised access to both (Berger, 1984).

That there are many centres of the world is not a daunting paradox, according to Voth, “because the nature of a sacred place admits many centers, each revealing a longing for transcendent forms” (Voth, 2010, p. 105). In her longing, the child Liv in my novel, senses the world outside her safe and sacred sites. She collects what is revealed to her, and she makes her own perfect sense of it all – of what she can continue to become with the world, and what she needs to do in her own ways. Eventually she leaves the home and enters the forest surrounding the farm, and the events of her own stories can commence.

Potentialities of dangers, surprises and adventure

The idea of becoming in post-human thinking emphasises the ontological: that which fundamentally exists. The subject is not regarded as the starting point for existence; in this case it is not Liv, as the subject that makes rational and logical choices. Rather, Liv becomes, as a temporary result of movements, where different components and potentialities are linked together (Manning, 2014). As in the shadows of the theatre, or in myths and fairy tales the darkness surrounding Liv`s sacred hideouts, and other components appearing in the scenes, are linked to potentialities of dangers, surprises and adventure. A dwelling, the house, the home, become a center of the world, and a safe and sacred place for Liv, but they can also become lenses, mirrors or gateways, and give access to the unknown.

Donna Haraway’s phrase “staying with the trouble” (Haraway, 2016) implies an invitation to enter into the uncertain, into complicated questions and chaos; into becoming with the trouble. Uncertainty opens up space for new knowledge productions that can include uncertainty, fragments and ambiguity.

Courtesy: Galleri Magnus Karlsson

Sacred sites

Sites or places become sacred because something important took place there – history and life changed because of what played itself out on the site or place in question. “Sometimes a sacred place is imaged as an omphalos, a world navel. All such places suggest a “nostalgia for paradise,” a desire to be at the heart of the world and of reality” (Voth, 2010, p. 91).

The landscapes and dwellings of childhood are lost to most of us – hideouts at the farm where I grew up are not physically accessible to me any longer. This is a nostalgic fact, but it is also productive: these now embodied, fragmented and porous images of landscapes and places are in constant change, and this ongoing blurring holds potentials for new beginnings – new narratives.

A similar perspective of landscape, place or dwelling is examined by Tereza Stehlikova in On mental morphology (2013). Among others Stehlikova sites Gaston Bachelard who quotes the German poet Rainer Maria Rilke: “I never saw this strange dwelling again. Indeed, as I see it now, the way it appeared to my child’s eye, it is not a building, but is quite dissolved and distributed inside me: here one room, there another, and here a bit of a corridor which, however, does not connect the two rooms, but is conserved in me in fragmentary form. Thus the whole thing is scattered about inside me, the rooms, the stairs that descend with such ceremonious slowness, others, narrow cages that mounted in a spiral movement…” (Stehlikova, 2013).

The scenographic writer

A place that is sacred, need not be a geographical site – it can also be imaginary or internal, the human body being a primary container (Le Guin, 2019). The crossing of the vertical and the horizontal lines and the reassurance their intersection promises, was probably already there in the thinking and beliefs of nomadic people, John Berger writes. The nomadic people carried the vertical line with them, as they might carry a tent pole (Berger, 1984).

Compared to my ancestors at the farm, I lead a nomadic life, and the early experience of nature has become part of my nature – of who I continue to become in creative processes, also in the act of place orientation as a scenographic writer. I carry the tent pole with me.

In the mirror in the hallway, the blood on Liv’s T-shirt is a map. By her heart is the pond in the forest and the marsh. On her stomach: the farm and the farmyard, the flagpole where the navel is. The farmhouse by one kidney, the barn with the hayloft and the barn bridge by the other. Under her ribs, the road crosses the yard. Around the barn, by the ovaries and uterus, the valley with cornfields spread outwards. On the hills: field flowers and cows during the day, deer at night. The forest and the mountain are reflected in the lake below the farm, with the trout and the eel. From the lake: the stream, the river, the fjord, the sea, the rest of the world. (Odel, 2023, p. 28)

Courtesy: Galleri Magnus Karlsson

On not knowing

For my exam in ceramic arts in the early nineties, I worked with the idea of hiding, inspired by the memory of hiding as a child. I made sculptures shaped as tunnels, dwellings and hideouts in wet clay, strengthening the clay constructions with trees from the yard outside the art college. The caretaker had cut down the trees the previous fall, and through the winter I had seen the tree logs lay silent, stored up in piles in the college back yard.

My exam was the following spring, and the caretaker let me have the logs; they were meant to be tossed away anyway. I exhibited my clay and tree log sculptures in the college gallery, and after just a short period of time, the dried tree logs were awakened from what appeared to be hibernation by the moisture of the clay and the light from the spring sun shining through the windows of the gallery. The tree logs drank the water in the clay and numerous new sprouts stretched towards the sunlight. The sprouts grew to new branches with large green leaves, and the clay dried out and turned to sand. My hideouts had become a forest.

I never plan my writing and I never planned on making a forest for my ceramic project either. But there it was, like a blessing.

To me, as a scenographer, sculpting clay, crafting scenography and writing novels are all acts of place orientation; they are acts of play and discovery, of not knowing and of becoming. I make art to connect, to understand and to investigate my entanglement with the world. But I also make art, to disconnect, to get lost, to forget myself and to follow wherever the paths in the forest take me.

Extracts from the novel Odel (2023), Det Norske Samlaget (New Norwegian). Translated by the author.

References

Berger, J. (1984) and our faces, my heart, brief as photos Pantheon Books.

Hann, R. (2019) Beyond Scenography Routledge.

Haraway, D. J. (2016) Staying with the Trouble. Making Kin in the Chthulucene, Duke University Press.

Le Guin, U. (2019) The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction, TJ Books Limited

Manning, E. (2014) Wondering the World Directly – or, How Movement Outruns the Subject

Body & Society. Volume 20, Issue 3-4: Special Issue: Rhythm, Movement, Embodiment. September & December 2014. Pages 3-226 DOI: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/epub/10.1177/1357034X14546357

Stehlikova, T. (July 31, 2013) On morphology. Cinesthetic feasts. Tereza Stehlikova: Artistic research into sensory perception & embodiment. https://cinestheticfeasts.com/2013/07/21/on-mental-morphology/

Voth, G. L. (2010) Myth in Human History. The Great Courses. The Teaching Company.

Dordi Strøm (b. 1971) is a Norwegian scenographer, costume designer and writer. She is also a trained ceramicist and teacher and is interested in interactions between human, the more-than-human, place, landscape, myths and fairy tales. Her upbringing on a farm and her background from a nomadic life as the daughter of an ornithologist are strongly present in her projects. She brings her knowledge of landscapes and animals – of nature and cultures that meet and change, and transfers this to her work. With this interdisciplinary approach, she asks what scenographics as place orientation does, and in what contexts art can be included. Place orientation as polyphonic conversations between human and more-than-human and as source for new narrative, in a time of ecological crisis, is central to this work. Strøm´s latest novel, Odel (2023), has received brilliant reviews in Norwegian newspapers and is described as “spooky, suggestive and sparklingly original”.

www.dordi.no