TT Journal, ISSUE 6, September 2023

By Nuala Clooney

“Taste alone compels the eating, not hunger for the word. It is as though the soul can taste sweetness beyond the body: the trope of sweetness is that interiorisation discussed earlier, except that the sweetness is tasted in the mouth, an orifice of the body.”

(Dunne and O’Rourke, 2013)

In this text I explore some of the playful approaches and methods that I embody in my artistic practice. These approaches enable my sense of self to keep safe but also allow me to address more difficult experiences and emotions. Play, or rather playing, is a strategy that I use in my studio practice. Using the term ‘playing’ rather than ‘working’ allows me to submerge myself into a more fluid, sensory experience where I rediscover parts of myself through heightened sensing. When I play, I extend knowledge that is buried beneath, bringing my thoughts and feelings into the embodiment of my work.

This text has been grouped into the playful themes that I explore and use to make my work.

Senses at Play

We use our senses to navigate the world around us. Our senses allow us to interpret and understand. Our bodies are vessels that carry and store memories and experiences; we summon these up to make sense of what we are experiencing in the present moment.

When someone or something leaves a metaphorical bad taste in our mouths, we might choose to block that memory, hiding it from view or from our taste buds.

“you fill his mouth

his teeth ache with memory of taste”

Warsan Shire (an open book, 2016)

What happens, however, when we are unaware of how we actually feel or when we misplace anxiety for excitement? What if some experiences are so painful to think about that we have buried them deep inside our psyches? Negative or challenging memories are corporeally swallowed. Our bodies store them within their dark folds. In the shadows, such memories lurk, hidden from plain sight yet our tongues hint towards their existence.

It’s on the tip on my tongue …

Playing with food is a tactile and sensory experience and, in my artistic practice, I use play as a tool to reveal the unconscious feelings that I have buried. This idea is akin to anthropologist David Howes’ notion of touch: ‘skin knowledge’.

(Ceramic wooden tool, acrylic teeth and custard)

‘Skin knowledge’ is what Howes explains as a form of bodily knowing and sense-making. Our skin is an interface between us and everything else, it provides us with a sentient experience of the world. (Blackman, 2021)

“‘The skin is not simply a physical protective covering but one that also creates the possibility of a different kind of bodily knowing.” (Blackman, 2021)

For me, skin knowledge extends beyond. It is infinite. My mouth, my tongue and my teeth are a continuous surface in which things emerge and return. The permeability of my mucous membrane allows for a mutually reciprocal conversation. It is a ‘mouthfeel’ that encompasses texture and sensation but also feeling.

“We eat the colour of a cake, and the taste of this cake is the instrument which reveals its shape and its colour to what we may call the alimentary intuition. Conversely if I poke my finger into a jar of jam, the sticky coldness of that jam is the revelation to my fingers of its sugary taste. The fluidity, the tepidity, the bluish colour, the undulating restlessness of the water in a pool are given at one stroke, each quality through the others; and it is this total interpenetration which we call the thing.”

(Sartre, 2018)

Sensitive, curious tongues extend out of the oral cavity. They lick to taste. (A worm, wiggling, writhing, and flexing its muscles forward, secretes a saliva-like fluid that seeps through its body, allowing it to sense, make sense and feel its world.) Once returned to the mouth, our tongue and our teeth chew this information into a viscous soup that is easily swallowed and reincorporated.

‘The Viscous is a state halfway between solid and liquid. It is like a cross-section in a process of change. It is unstable but it does not flow. It is soft, yielding and compressible. There is no gliding on its surface. Its stickiness is a trap, it clings like a leech; it attacks the boundary between myself and it. Long columns falling off my fingers suggest my own substance flowing into the pool of stickiness.’ (Douglas, 1996, p157)

Making Sense

I see my studio in the same way that I used to view my bedroom as a child. It’s where I go to play. It is a facilitating environment filled with objects, tools and materials. I begin with object play and, often, these objects have an association with the mouth. I explore them through my senses and manipulate them. First, I navigate between what is felt and sensed, initially responding to fuzzy, gut-felt reactions to what the object is, how it feels and how it makes me feel. At this point I am unable to articulate what it is that the work is about; my felt sense is in control, and it seems to know what it wants to create. After time and reflection, I start to move past gut feelings to playing with how the object then symbolises something ‘other’.

an Arts&Heritage project. Image credit: Jonathan Turner

Metaphors are made, objects trigger memories, which alongside material play, lead to a transgression of the function of the original object. In this sense the object is a ‘transitional object’ that connects the inner subconscious felt sense with the outside world and awards me with renewed agency.

“She had no external notion of a world outside of hers. I saw her as a very interior person making psychic models.” (Quote by Robert Smithson on Eva Hesse (Lippard, 1992))

Myself as the subject of my work is explored alongside my relationship to the works as objects: I, the subject become the object. In casting parts of myself into various intimate vessels, these objects become extensions of myself, informing my understanding of intimacy.

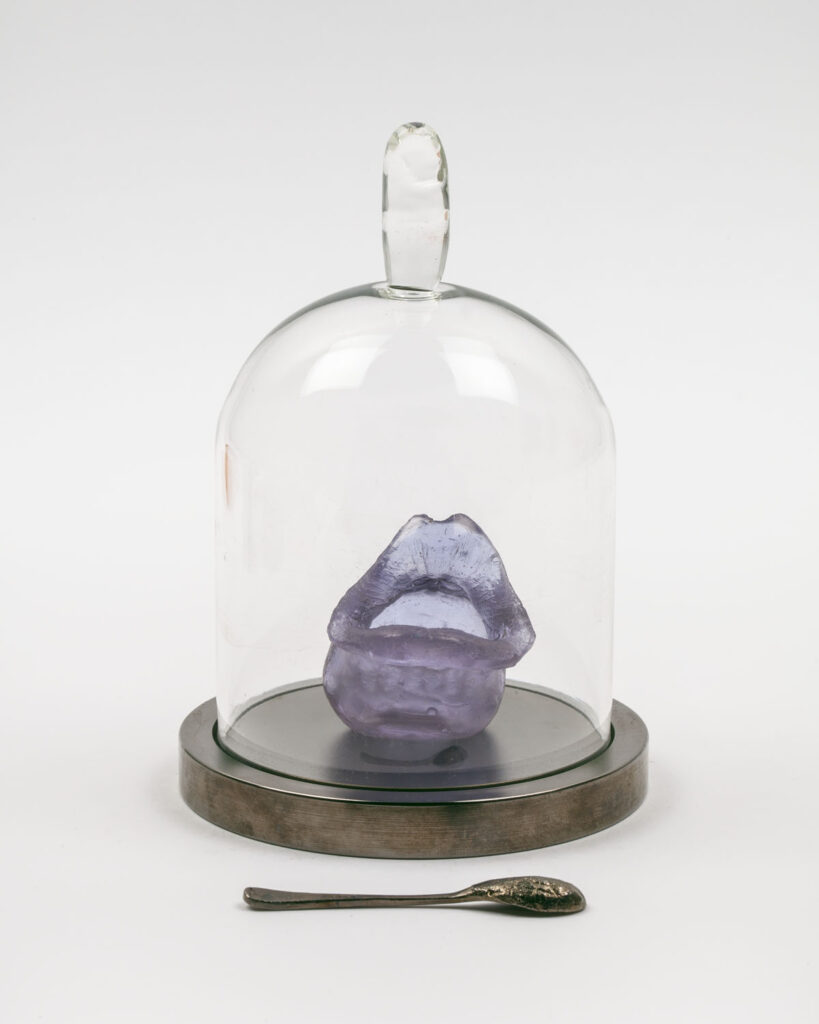

The process of casting the void of my own mouth means I am fully immersed in a tactile exchange with material. My mouth intimately holds the material, and the moulding process combines us in union until it sets. This experience transports me to memory, to kisses that invasively filled my whole mouth, a feeling of both being force-fed and being consumed at the same time.

“Being the most intimate and regressive of sensations, kissing is almost likely to evoke the fear of being destroyed and devoured.” (Coward, 1984)

I turn myself into objects that are intimate vessels for sustenance. They contain and are, in and of themselves, a bodily gesture suggestive of a desire to be kissed, sat in suspension and vulnerability.

“Duchamp’s object is an object of measurement. It’s in suspense, held in time, unfolding itself continuously at the same moment, a constant reminder of the longed for and the about to be.” (Barlow, 2014)

This allows me to explore the senses of intimacy in a broader context than that of my own experiences. In 2016, I explored these objects as performing objects when they were used within an experimental dining experience titled ‘After Dark’ designed by artist Kaye Winwood. The textural surfaces of the implements used evoke sensations of the visceral and communicate bodily connectedness, intimacy, and union. Through interaction with the tools, participants were invited to eat and lick from another body and therefore to connect with the ‘other’ and in turn, each other, initiating an experience which might be both sensual and alarming.

The everyday function of objects such as spoons, honey jars and drinking vessels are, in this way, extended and transgressed. The experience they ignite subverts our normative experience of drinking and eating, creating a confusion of the senses for an audience. This confusion between kissing and consummation is described by Dr. Paul Geary:

“I was kissed, but not by the lips of another person directly, but by the model of the lips of another, transformed into hard material that did not give or respond to the pressure of my own. Embodied memories of previous kisses and drinks were recalled precisely in the strangeness of this present experience to those of the past. It was not entirely new; it bore the traces of something familiar, something that goes without thinking. But nevertheless it was strange and so my attention was drawn to the very experience that is usually taken for granted. I was forced to experience my own body and its sensations in a different way.” (Geary, 2020)

Playing with form

Using wax as a material, parts of my body are interconnected with bits of cutlery and tableware. This is true of my works Lip-Spoons and In Memory of You. Wax is a sticky substance that is unstable (Didi-Huberman, 1999) allowing me to metamorphose two bodies into each other. The plasticity of wax allows me to physically witness the changeable nature of being, watching it move between form and formlessness. I am confronted with my own vulnerabilities. Wax is not passive as it carries traces of my lips and fingers. Didi-Huberman characterises this as the power of material (1999). The changing state of wax and body is then transformed into a fixed state of cast metal or glass and so distills a gesture, a bodily message to the receiver.

“We act out our state of being with non-verbal body language. We lift one eyebrow for disbelief. We rub our noses for puzzlement. We clasp our arms to isolate ourselves or to protect ourselves … The gestures are numerous.” (Blackman on Fast, 2021)

“The body’s gone beyond itself beyond the boundaries of being contained by the skin. It’s out there floating in the elements, as cells drifting.” (Chadwick, 2005)

“The honey which slides off my spoon on to the honey contained in the jar first sculpts the surface by fastening itself onto it in relief, and its fusion with the whole is presented as a gradual sinking” (Sartre,2018)

Sensory Materials

My work utilises multi-sensory participatory approaches that include dining interactions, exhibitions and socially engaged projects. These methods are used as seductive strategies to engage an audience’s sensory perceptions. The work aims to challenge and ignite conversations around developing a knowledge of our sense of agency in relation to food and in relation to objects.

Sweet foods are prominent within my work and, indulging the senses, my work invites audiences to play with their food. Jelly and sweets, in particular, remind people of childhood. By focusing on the sensation of taste in the mouth, a crucial orifice of the body, the work creates a more intense sensory experience, childhood likes and dislikes becoming blurred with grown-up sensual and sexual experiences.

Jelly, especially, is a substance that behaves like a body. Its sinuous properties allow it to flex, stretch and bounce back, akin to an independent muscle flexing. In this case, the quality of material extends beyond its physical attributes and feelings permeate our experience of them. Jelly weeps, wobbles, droops and so do we.

Marshmallow operates similarly. The marshmallow membrane is described by filmmaker Tereza Stehlikova in the following terms:

“I observe the flexing muscle of sweet jelly, the stretching of its pink ligaments.” (Stehlikova, 2018)

In the work ‘sweet muscle flexing’, the sticky membrane of marshmallow becomes ingested and forms part of performer Tereza Kamenicka’s body, whilst she takes the remnants and rubs its pink ‘ligaments’ into her skin as a way of completely incorporating ‘the other’.

In 2018, artist filmmaker Stehlikova and Kamenicka spent a day in my studio for an ongoing artistic research project that is exploring embodiment, ingestion, and the exchange between inside and outside, engaging with all the senses. I playfully laid out my objects and sweet treats.

Being mindful of flavours and textures, I prepared sweet, lavender nipple meringues, crystallised rose petals, chocolate casts of my tongue that had a rose fondant centre, a plate made from chocolate, which became limp and started to melt away and a rose-flavoured marshmallow.

There were no instructions or rules. Performer Kamenicka was given full reign to respond and to interpret the work as she pleased. Whilst she played, consumed, and explored the work through her senses, Stehlikova filmed the interaction. The intense heat of the day, made the ‘sticky’ objects flop, melt and reform into Kamenicka’s body more noticeably. The blurring of self and other became more unstable.

Our sensory experience of these sorts of materials are complex, messy and intertwined, making it hard to distinguish and define our perception of which sense is activated.

Sinuous – rippling – bouncing – waving

We have inside-out emotions. Language permeates experiences and all the while we attribute human feelings and qualities to objects and materials.

Sweet Metaphors

We use language to shape and control the things around us. Sweet metaphors are used as linguistic tools to aid our understanding of abstract concepts such as romantic and family bonds. Sweet words are used as terms of endearment and sexual implication: ‘sweetie’ ‘honey’ ‘sugar’. (Wang et al., 2019)

In listening to the Radio 4 programme Sweetness and desire: A short history of desire (2019), I have become more aware of how confection affects the body and our sense of identity in relation to gender and the socio-political. I am particularly interested in the notion that our brains sometimes struggle to tell the difference between sweetness and love. As food writer, Bee Wilson wrote in her book First Bite (2016), “Sugar is not love, but it feels like it.” Perhaps this is because breast milk is creamy and incredibly sweet. We associate the taste of sweetness with feelings of comfort, satiation, safety, fullness and of our mothers. It connects to what is considered female.

“No sugared association is stronger than that between sweetness and femininity. Girls are made of sugar and spice and everything nice. Women are honey, sweetheart, cupcake, candy girl, honeybunch — or they’re tarts. In the Bible, “The lips of an adulterous woman drip honey” (Proverbs 5:3). Meanwhile, black women have been “caramel,” “brown sugar,” “mocha latte,” “chocolate,” and “molasses” — both desired and diminished.” (Tandoh, 2018)

(commission as part of Meeting Point, an Arts&Heritage project). Image credit: Jonathan Turner)

The five approaches of play explored in my practice are the tools I use to reach an internal sensing that is not just intuitive but is an investigation in which my somatic experience is heightened. This allows me to understand how senses and emotions are interconnected: how they play off each other.

The intimacy in which I make my work can be felt within the objects and food I make. This offers me more opportunities to explore themes such as vulnerability, seduction, play and intimacy with care and sensitivity. It further offers understanding of how experiencing art through a more accessible and embodied way can help us rediscover how we once played, touched, and enjoyed the world as children.

References:

Betterton, R. (1996) An intimate distance: women, artists and the body. London: Routledge.

Blackman, L. (2021) The body : the key concepts. Second edition, London: Routledge.

Coward, R. (1984) Female Desire. London: Paladin.

Dunne, É. and O’Rourke, M. (2013) JAM. Parallax, 19(1), pp. 50-63.

Geary, P. (2020) An-aesthetic: Performed philosophies of sensation, confusion, and intoxication. Performance Philosophy, 5(2), pp. 293-302

Barlow, P (1996) The Sneeze of Louise. In Hudek, A. (2014) The object. London: Whitechapel Gallery and MIT Press, pp199-201

James, N. P. (2005) Helen Chadwick: of mutability. London: CV Publications.

Didi-Huberman, G (1999) The order of material: Plasticities, malaises, survivals. In Lange-Berndt, P. (2015) Materiality. London: Whitechapel Gallery.

Lippard, L. R. (1992) Eva Hesse. New York: Da Capo.

Sartre, J.-P. (2018). Being and Nothingness: An Essay in Phenomenological Ontology (S. Richmond, Trans.; 1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429434013

Wilson, B (2016) The first bite: How we learn to eat, Fourth Estate

Wang, L., Q. Chen, Y. Chen and R. Zhong (2019). “The Effect of Sweet Taste on Romantic Semantic Processing: An ERP Study.” Frontiers in Psychology 10.

Websites:

An open book, 2016 Warsan Shire, For Women Who Are Difficult To Love. Available at : Warsan Shire – For Women Who Are Difficult To Love – YouTube (Accessed 04 May 2023)

Stehlikova, T (2018) Sweet Muscle Flexing. Cinesthetic Feasts (blog) Available at: sweet muscle flexing – Cinesthetic feasts (Accessed 04 May 2023)

Tandoh, R (2018) The Primal Pleasure and Brutal Pleasure of Sugar. Available at: The Primal Pleasure and Brutal History of Sugar – Eater (Accessed 04 May 2023)

Sweetness and Desire: A short history of Sugar, The Lure of Sweetness (radio programme) Presented by Bee Wilson. BBC UK, 23 Jan 2018, BBC Radio 4, 14 mins. Available at: BBC Radio 4 – Sweetness and Desire: A Short History of Sugar, The Sweet-toothed Nation (accessed 04 May 2023)