TT Journal, Vol.1, ISSUE 2, 19th March 2021

by Kaye Winwood

There are many of us who delight in discovering the world through our senses.

We are acutely aware of our environment; we smell odours captured in molecules carried on the breeze; we hear sounds that disrupt the silence, and silences that punctuate the clamour; we enjoy the touch of cool metal against our skin as much as the heat of a child’s gripping hand; we delight in the unexpected grain of salt lodged beneath our fingernail and the pungency of ripe fruit dribbling down our chins that is swiped clean with a flick of the tongue.

Our senses are sharp and eager. Ready and impatient. But overwhelmed, an assault on the senses can provoke an intense physiological response that’s not always welcome, like swimming into a cold spot in the sea, or smelling putrefied food. Adversely, other bodily sensations such as salivation, breathlessness or goosebumps might be the response to a profound pleasure experience.

We find the smell of food particularly emotive. It’s fragrance transports us back to childhood memories, places we have visited, and reminds us of people we have shared food with. In these isolating times of Covid when shared intimate exchanges are not possible, perhaps we can transgress restrictions by harnessing our senses to time-travel and invoke pleasurable experiences.

Let’s use our senses to simulate forgotten moments, to recall the smell of another’s skin, to taste the lips of a lover. For, after all, we are bodies composed of thousands of receptors, intrigued to receive the unfamiliar and poised to cherish the familiar.

We are always alert, we are sensualists.

Food is so much more than nourishment. We invest emotionally and economically into the experience of eating. Recipes establish a sense of belonging; ingredients evidence wealth and status, demonstrating our choices and tastes; and ultimately food provides pleasure for the most wanton of appetites. It is the latter – food as a sensory pleasure – which is my focus.

If we didn’t want to enjoy our food we could – as Marinetti suggested – become more efficient by replacing food with an easy to swallow pill providing us with all the nutrients we need.1 Since it is proven that “human beings are technically able to cover their daily calorie intake without eating” why do the senses play such an integral role within dining.2 Historically the senses have alerted us to dangers and poisons, more recently our senses are being harnessed as tools to experience indulgence and pleasure.

I have used food as an art material for over 10 years. During this time I have been eager to explore the visceral and physiological effects of food and its potential to assault the senses and arouse pleasure.3 I am interested in exploring what specific attributes transform the everyday act of eating from mundane to sensational, and which of their properties are perceived to be sensual?

On considering sensuality, I think it’s important to acknowledge the multisensory nature of eating which draws on, not one but, all five of our senses in a kind of synaesthetic experience regarding to how the food looks, tastes, feels, sounds and smells. Our senses are constantly engaged, to an extent that their presence often goes unnoticed. It is usually when our senses are alarmed, assaulted or aroused that we become aware of their presence.

Olfaction makes a significant contribution to what we taste. As a result of Covid we are increasingly aware of anosmia (loss of smell) and the effect it has in decreasing our ability to taste; but it may be that the effect of olfaction on taste is not so recognised. The process – ‘retronasal’ smell – enables air to travel freely through the nose, carrying edible odour molecules to the olfactory receptors. When these molecules reach the receptors they are perceived as flavour. Whilst this example may be quite rudimentary, it begins to demonstrate the simultaneity of flavour perception between smell and taste which is a key factor when considering the multi-sensorial experience of eating.

Leading some of this scientific research is Professor Charles Spence who has written a number of seminal books relating to the science of eating and multi-sensory perceptions.4 His research evidences clear links between how perception can affect the way we eat, attributing colour to our perception of sweetness, and sound to our perception of crispness. Spence’s research is undeniably pertinent to international discussions around food design, obesity and flavour enhancement, but surely it can also be applied in considering multisensorial food experiences within an art context.

So much pleasure can be attributed to eating. Our eyes hungrily consider shape and form, texture and colour; the reflective sheen of liquids and the caramelised char on edges make us salivate. We greedily cup our hands to capture the floating volatile molecules carrying smells to our noses before fingering the food and sucking our glistening fingertips. Our lips, mouths and tongues poised and titillated, sensing taste, texture, and temperature of each morsel they touch.

“They did not merely taste the cuisine with their tongues: they had to taste it with their eyes, their noses, their ears, and at times their skin. At the risk of exaggerating, every part of them had to become a tongue” The Gourmet Club, Jun’Ichiro Tanizaki 5

In the hierarchy of pleasure there can be no denying that eating is the closest hedonistic pursuit after sexual activity. They mirror each other in so many ways. Our hands, lips, fingers and tongue share a gestural language with sex – probing, gorging, cupping, licking, sucking.

Excerpt from a love letter from Arthur Miller to Marilyn Monroe:

I will kiss you and hold you close to me and sensational things will then happen. All sorts of slides, rollings, pitchings, rambunctiousness of every kind. And then I will sigh. And when you rest your head on my shoulder, then slowly I will get HUNGRY.I will come again to the kitchen, pretending you are not there and discover you again. And as you stand there cooking breakfast, I will kiss your neck and your back and the sweet cantaloupes of your rump and the backs of your knees and turn you about and kiss your breasts and the eggs will burn.

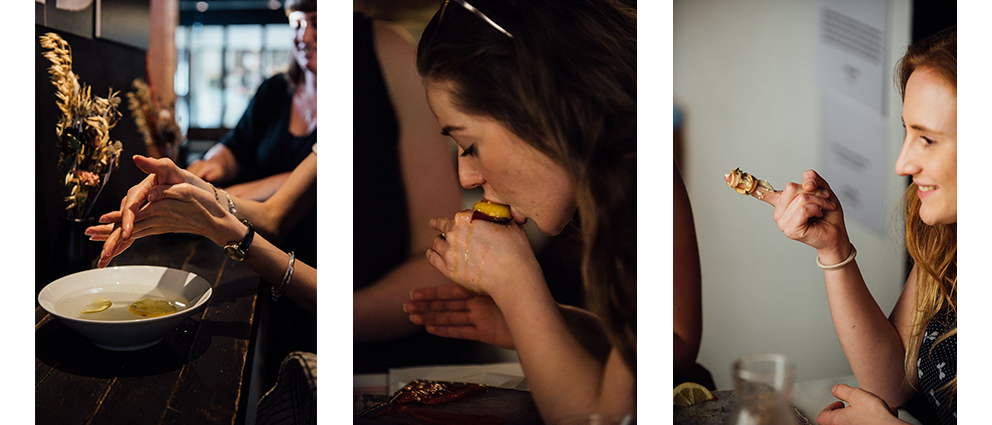

In 2018 I began a new piece of research exploring the sensual potential of food within a series of work called Hands On Sensuality. I used this shared gestural language to formulate a menu based artwork, which was part performance/part dining experience. The work started as one-to-one inquiries in my studio before I began to conduct them as public events with small groups of people in intimate settings. The experience explored gesture and touch to reach an intense and heightened sensuality, directly relating the visceral sensations shared by eroticism and eating.

Hands On is “…a feast for the senses, it is a performance that requires indulgence, a combination of the social, artistic and technical elements of food and its consumption.” Tom Glover

Each performed experience began with the ritual of cleaning hands. Using a home-made edible scrub I unhurriedly massaged and dried the participant’s hands, all the time making hushed conversation about ingredients and the performance – literally holding their hands to assuage nerves and inhibitions and to familiarise them with the continuing action of being touched. The lingering smells and moisturised skin were a further evocation of indulgent sensuality. Participants were asked in advance not to wear perfumes and, after cleansing, they were given a piece of lemon to cleanse their hands between courses. They were asked not to wash their hands with soap during the experience so that the olfactory properties of the unfolding multi-course menus were not influenced.

‘Cooking is probably the most multi-sensual art. I try to stimulate all the senses.’ (Ferran Adrià, El Bulli restaurant, Spain)

Several courses – sometimes as many as 12 – were fed to the guests in a deliberate performance. Using a choreographed and rehearsed journey around the topography of the hand I was able to trace dips, crevices, indentations and cracks of the hand which could hold food – exploiting the formation of the hand and how that fleshy domain would engage with the mouth, lips and tongue to explore and consume. The hands and fingers provide a perfect vehicle to receive and eat food. These multifunctional tools can swipe, scrape, dip, scoop, hold, squeeze, poke, cup, grab, grasp, pinch, shake, asserting different levels of pressure to suit the task.

There is something libertine about eating with the hands, whilst often considered the basest of actions it can feel incredibly indulgent and empowering.

After Cunnilingus, Hollie McNish[6]

when you looked up

there was so much

mess around your

mouth, you wiped

a full arm swipe

across your lips

tongue grabbing

final licks of me

like children

clearing pussing

bowls, brim full

of ice cream

It is unfortunate that during the pandemic resulted in a sharp decline of sensory engagement. As a result of social distancing and limited social interaction we have become accustomed to engaging with people in 2-dimensions with Zoom as our new normal. The arts and hospitality sectors have suffered immeasurably, and as I write this, we are still unable to meet in person, and restaurants, art galleries and theatres remain closed.

For many of us, the loss of sensory engagement caused by Covid has affected our appetite for intimacy on many levels. We are becoming sensorially starved. But what if we actively start to exercise our senses again? As John Cage demonstrated with his controversial musical performance 4m33s, when we take the opportunity to listen to ‘nothing’ we begin to hear the imperceptible.6 Perhaps this deprivation is the very stimulus we need.

I have written a sensory menu for you. Try it at home by yourself or if you’re lucky to have someone with you, you can experience it together. Enjoy your inner sensualist.

A PERFORMANCE MENU FOR SELF-PLEASURE

References:

1) La Cucina Futurista, first published 1932

2) Food design XL. Published by Springer Wien New York. 2010

3) When I talk about ‘food’ I refer to a broader set of circumstances around food, as explained by Dr Elisa Oliver in Expanded Dining, “Food is central but not definitive to Winwood’s practice. Working with the tools and paraphernalia of cooking and dining the work uses food as a pivot that enables a range of discourses to come into focus.”

4) Charles Spence is a Professor of Experimental Psychology at Oxford University where he leads the Crossmodal Research Lab. His publications include Gastrophysics: The New Science of Eating , published Penguin, 3 May 2018 and The Perfect Meal: The Multisensory Science of Food and Dining , published by Wiley-Blackwell, July 2014

5) The Gourmet Club: A Sextet, published by Kodansha International Ltd (1 Aug. 2001)

6) Many thanks to Hollie McNish for agreeing to let me include After Cunnilingus within this contribution.

7) First performed August 29, 1952 in New York.

Kaye Winwood has an innovative creative practice, inviting audiences to engage sensorially with unique environments and objects. Her work fuses sensory design with visual arts and gastronomy to create new and meaningful eating environments which enthral diners. In 2016 she applied the term ‘Expanded Dining’ to reflect a ‘beyond the plate’ approach which reconsiders the dining experience as a sensorial playground using food as an art material. Kaye is a studio holder at Grand Union Studios in Birmingham, and an Honorary Research Associate at the University of Birmingham; In 2018 she was awarded a Feeney Fellowship and since 2016 she has peer reviewed the online journal FEAST. Kaye’s website: http://www.kayewinwood.com/

All images by Jo Ritchie. ‘Hands on Sensuality’ produced by Kaye Winwood with Food/Theatre Producer Christie Hill (Leeds Indie Food Festival)